“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

The preceding quote is the introduction to Charles Dickens’ immortal classic A Tale of Two Cities, set in Paris and London around the time of the French Revolution, but it’s also a pretty damn accurate description of the state of the guitar industry during the ’70s.

That decade is commonly disparaged as a depressing era when the industry’s leading manufacturers produced some of their worst guitar models, which is not entirely untrue, but it also was an auspicious period when exciting new guitar companies emerged and amp and effect technology rapidly advanced.

The decline of America’s biggest guitar companies during the ’70s was essentially a hangover from the over-ambitious reaction to the Beatlemania-inspired guitar boom of the ’60s. Hoping to cash in on the phenomenon, major corporations purchased America’s biggest guitar companies, with CBS buying Fender, Norlin purchasing Gibson and Baldwin taking over Gretsch.

Although the electric guitar remained massively popular during the ’70s, sales dropped rather steeply from the staggering heights of the ’60s peak. In typical corporate fashion, management typically believed that the accounting department’s cost-cutting measures were a more effective means of maximizing profits than investments in better materials, tools and craftsmanship, and quality took a hit as a result.

That isn’t to say that the instruments Fender, Gibson, Gretsch and others were making during the ’70s were actually bad. Many players who own ’70s guitars from these companies can attest that the majority are decent, playable instruments.

The problem was that distinctly superior instruments from the Fifties and ’60s preceded them by only a few years, so the quality drop-off was much more dramatic and noticeable in comparison. The much higher cost of a new instrument during the ’70s (even when adjusted for inflation) further increased musicians’ frustrations.

The silver lining of the backlash to corporate mass-produced ’70s guitars is that it opened up and nurtured numerous other avenues that offered players compelling alternatives to the status quo. Smaller independent companies emerged that proved that you still could make a guitar like they used to and even improve it.

Japanese manufacturers progressed rapidly from building quirky oddball guitars during the ’60s to producing affordable copies of classic guitars that were surprisingly good during the early and mid ’70s and developing their own original models built with passion and pride in the late ’70s.

The vintage-guitar market rapidly blossomed as guitarists became more knowledgeable and discerning, and replacement pickup, body, neck and parts manufacturers offered convenient and affordable means for players to upgrade their instrument or even build one themselves.

For the most part, the only products that experienced dramatic drops in quality were guitars. Electronic gear like amps and effects improved in general, and most innovations in these areas were developed with players’ wants and needs predominantly in mind.

Rapid advancements in integrated circuit technology led to inexpensive, compact effects like flangers and analog delays, and amp designers finally accepted overdrive and distortion as qualities to embrace rather than eradicate.

Thanks to the abundance of guitar-dominated music that prevailed during the ’70s, gear from that era continues to hold a special place in the hearts of guitarists today. Here is a look at some of the finest examples along with a few admittedly flawed specimens that still manage to charm us after all these years.

Guitars

Major-Manufacturer Beauties and Blunders

Gibson’s age-old motto was “Only a Gibson is good enough,” but during the ’70s that seemed to change to, “It’s good enough, ship it anyway.” The downsides of the corporate takeover of the industry’s leading guitar companies during the ’60s went into full effect during the ’70s as shareholders and cost-cutting took precedence over players and quality.

Buck Dharma used an EBow on (Don’t Fear) The Reaper, and you really can’t get more ’70s than that without a mustache and white satin jumpsuit

Some factors were beyond the companies’ control, like the scarcity of Brazilian rosewood after Brazil ceased export of the tone wood in 1967, which caused the price to increase and supply to dwindle, making less-costly Indian rosewood a new standard tone wood.

But the big companies also tended not to leave well enough alone, making many design and construction changes that were often unnecessary, puzzling and unwelcome – features like multi-layered or patchwork multi-piece bodies that seemed to be as much glue as wood, overall weights that tipped the scales at 10 lbs. or more, low-quality or non-optimal electronics, cheap cast hardware, inferior tuners that slipped, heavily applied polyester finishes and so on.

Many bolt-on-neck Fenders suffered from haphazardly cut neck pockets with gaps that were large enough to easily slide a heavy gauge pick into. Gibson guitars often had useful features that guitarists generally didn’t want or understand, like neck volutes, the TP-6 stop tailpiece with fine tuners and the oversized “harmonica” bridge, which weren’t actually bad but were just different.

At the same time, a sort of if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em mentality inspired Fender to offer guitars with humbuckers and Gibson to start producing instruments with bolt-on necks and 25 ½-inch scale lengths.

Meanwhile, Gretsch decided to completely change the design of every guitar they made, which ranged from the decent (the 7594 and 7593 White Falcons, the 7670 Country Gentleman) to the hideous (the Roc Jet, TK300 and Committee, which actually seemed to be designed by a committee).

But like the winner of an ugly-dog contest, many of these models have found loving homes today. Some designs, like the Gibson RD Artist and Fender Lead series, were ahead of their time or simply too different from the classics to make an impression on players with staunchly conservative tastes.

Although luminaries like Ted McCarty and Leo Fender had left Gibson and Fender, respectively, before the ’70s, talented, visionary inventors were still employed by these companies, like electronics whiz Bob Moog at Gibson and legendary pickup designer Seth Lover at Fender.

Rise of the Vintage Guitar Market

In collector vernacular, a vintage item is usually something that is at least 20 years old. The irony of the vintage guitar market is that when it started to gain momentum in the early ’70s, the most highly coveted electric guitar models from the Fifties were barely in their mid-teens and technically were “used” guitars.

But thanks to high-profile dealers like GTR and Gruhn Guitars in Nashville, Norman’s Rare Guitars in Los Angeles and Mandolin Brothers, Matt Umanov Guitars and We Buy Guitars in New York, as well as a growing number of smaller dealers across the United States, the word “vintage” that they used to market classic instruments resonated with guitarists (although does anybody today refer to instruments from the ’90s as vintage?).

Numerous factors influenced a growing demand for vintage guitars during the ’70s, but the main driving force was the comparative decline in quality of new instruments as described above.

Ian Hunter’s entertaining and illuminating book Diary of a Rock’n’Roll Star also helped spark the vintage guitar fire during the early ’70s through his accounts of roaming pawn shops across the U.S. in search of classic American guitars and oddities while on tour with Mott the Hoople.

Rick Nielsen played a similar outsize role in stimulating vintage hoarding lust during the late ’70s, appearing on stage with Cheap Trick with row upon row of dazzling vintage and custom guitars on stands perched in front of his amp stacks.

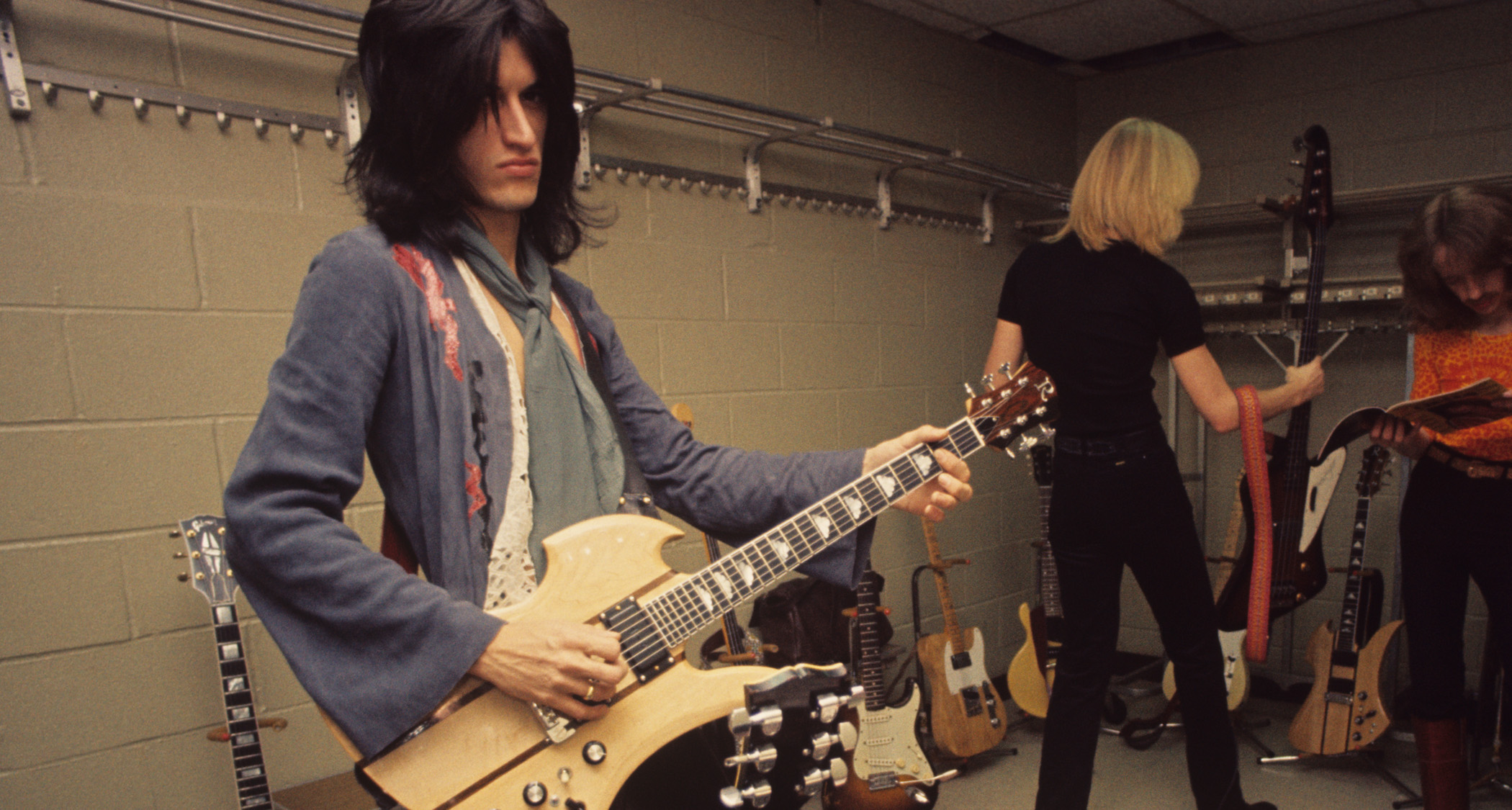

In fact, vintage guitars were a common sight for concert goers during the ’70s. Jimmy Page, Billy Gibbons, Joe Walsh, Joe Perry, Gary Rossington, Ronnie Montrose, Charlie Daniels and Gary Richrath were just a few of the main players who fanned the fire for flame-top 1958-60 Gibson Les Paul Standards.

Peter Frampton’s triple-humbucker 1954 Les Paul Custom, Neil Young’s “Old Black” and Jeff Beck’s “Oxblood” Les Pauls may have been heavily modified, but they inspired lust for black Gibsons. Clapton with his trusty Fifties “Brownie” and “Blackie” Strats and Rory Gallagher with his battered rosewood neck 1961 Strat helped make “pre-CBS” a household word with guitarists.

Although 1958-60 sunburst Les Paul Standards soared to prices starting at $2,000 and up during the ’70s, most classic Fender, Gibson and Gretsch guitars from the ’50s and ’60s, including Les Paul Specials and Juniors, SGs, non-reverse Firebirds, Strats, Teles, Jazzmasters, Jaguars, Duo-Jets and 6120s, cost about the same or even less than a comparable brand-new guitar.

Custom Competition

The less-than-stellar reputations of factory guitars from major manufacturers during the ’70s opened up an opportunity for a new breed of custom guitar builders who could provide a higher standard of quality for customers willing to spend a little more for an instrument.

The less-than-stellar reputations of factory guitars from major manufacturers during the ’70s opened up an opportunity for a new breed of custom guitar builders

B.C. Rich, Dean and Hamer were the most prominent and successful small companies that emerged during this time to fill that void. All three companies shared high standards of craftsmanship and attention to detail while also offering bold, aggressive designs that appealed to hard rock players.

Located in the greater Chicago area only a few hours drive from Gibson’s factory in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Hamer and Dean both built guitars that were essentially copies of Gibson’s Explorer (Hamer Standard/Dean Z) and Flying V (Hamer Vector/Dean V) models but using higher-quality materials.

Hamer also made the Sunburst model, which essentially was a double cutaway Les Paul with a flat top, while Dean also produced the ML and Cadillac, which were like a hybrid of an Explorer and a V or an Explorer and a Les Paul, respectively.

B.C. Rich offered original designs such as the Eagle, Mockingbird and Bich with features like neck-thru-body construction, built-in preamps and advanced switching options.

All three companies built instruments for an impressive roster of high-profile artists, and the exposure and ensuing demand helped them expand their offerings to include less expensive production models by the late ’70s.

Japanese Imports

A growing influx of affordable electric guitars built in Japan arrived in the United States where they were promptly welcomed by players looking for alternative instruments. Manufacturers like FujiGen Gakki, Matsumoku and Tokai Gakki gained a foothold by offering models that were copies of vintage and current Fender, Gibson and other popular American guitar models, sold under various brand names like Aria, Ibanez and Tokai.

The irony was that some of these companies like Matsumoku were also making budget models for American brands like Epiphone at the same time, which were not as highly regarded as their copy models.

Ibanez was the biggest success story of this development. The quality of Ibanez-brand copies increased each year as their craftsmen meticulously studied every fine detail of vintage examples

Ibanez was the biggest success story of this development. The quality of Ibanez-brand copies increased each year as their craftsmen meticulously studied every fine detail of vintage examples. Fujigen’s Les Paul copies quickly progressed from clunky bolt-on neck designs to set-in necks with long tenons like Gibson made during the ’50s.

Ibanez’s mid-’70s “korina” trio (actually made from Japanese Sen and finished with yellow hue that resembled korina) of Destroyer (Explorer), Rocket Roll Sr. (Flying V) and Future (their rendition of the mythical Moderne) looked cool, played well and sounded great, and – best of all – cost about the same as Gibson’s homely entry-level models.

These Japanese copies had gotten so good that the American companies pushed back by filing copyright infringement lawsuits, but Ibanez in particular was already one step ahead of them and was transitioning to their own original models by then. Ibanez’s Artist, Iceman and Musician models produced during the late ’70s were quite impressive thanks to all the knowhow they absorbed from studying the classics.

Acoustic Avenues

Although the C.F. Martin guitar company did not get snapped up by corporate ownership like most other large guitar companies during this era, they also experienced similar lapses in quality control during the ’70s.

More than any other company, Martin suffered the most when Brazil stopped exporting Brazilian rosewood in 1967 and they were forced to transition to Indian rosewood by 1969 when their supply ran out. However, the change to Indian rosewood was less of a problem than the increasingly heavy-handed building processes that Martin was using at the time.

Martin’s management determined that they were losing too much money from warranty claims, so they began building guitars with thicker braces and tops, heavier, more durable finishes and clunky necks.

The guitars were so overbuilt that you could probably use them as baseball bats without damaging them, but the sound quality was adversely affected. Just like with the electric guitar market, this led to increased interest in vintage Martins as well as an influx of low-cost Japanese copies.

Takamine made a huge splash with low-priced copies of Martin’s D-18 and D-28 dreadnoughts, and Alvarez-Yairi made higher-end copies for players who didn’t mind spending a little more. Yamaha also increased its market share significantly during this time thanks to aggressive distribution efforts.

It wasn’t all bad news for American-made acoustics though. Guild continued to make good instruments throughout the decade, and their 12-string models from the ’70s in particular are highly regarded.

Ovation introduced its first models during the ’60s, but the brand truly came to prominence during the ’70s as Ovation and their offshoot Adamas brand acoustic-electrics became common fixtures on concert stages.

Parts Is Parts

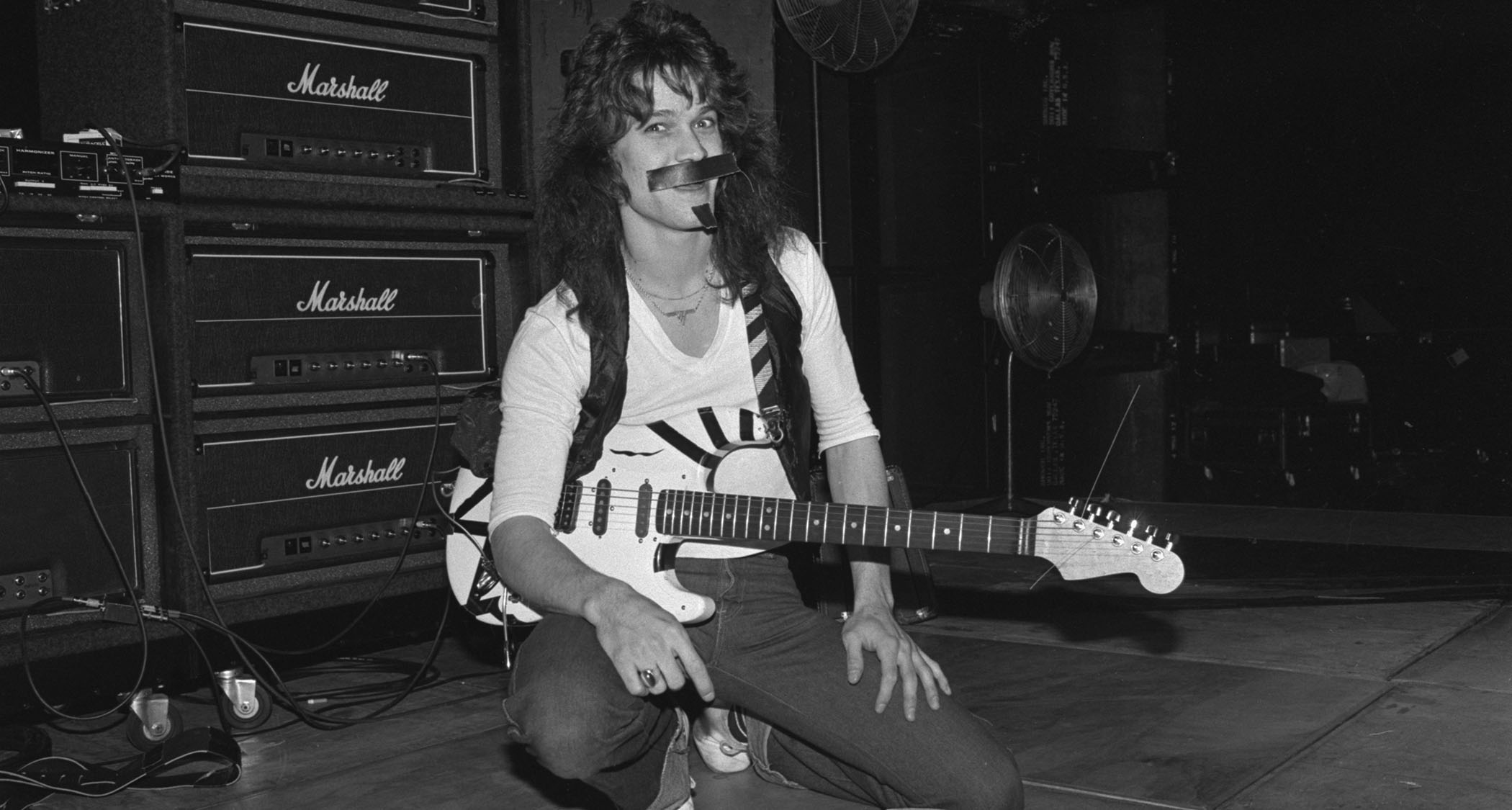

If you couldn’t afford a custom guitar from Hamer or B.C. Rich and didn’t want a Japanese import, another appealing alternative for guitarists was to build their own instruments using pre-made bodies and necks and upgraded replacement parts that had started appearing on the market.

This approach got a huge boost when Eddie Van Halen burst onto the scene in 1978 playing a black and white striped custom Strat that he cobbled together from scrapped parts and a neck and body that cost him less than $200. Boogie Bodies, Charvel, DiMarzio and Schecter were the leading sources for DIY guitar builders who wanted to make their own custom hot rods or upgrade their factory instruments.

Amps

High-Gain Heroes

Randall Smith’s Mesa Boogie amps featuring a revolutionary cascaded high-gain preamp design forever changed the guitar amp industry. The Mesa Boogie Mark I amp introduced during the early ’70s gave guitarists greatly expanded control of overdrive and saturation over a wide range of volume levels ideal for small venues and recording studios to large concert stages.

The tones of the Mark I were thick, luscious and sweet, providing a vast tonal palette, thanks to its reactive tone controls and optional 5-band graphic EQ and delivering a musical expressiveness that slayed the competition. The Mark II model introduced during the late ’70s was the first production amp to offer channel switching, paving the path for today’s multi-channel high-gain amps.

Master of Volume

By the dawn of the ’70s, Marshall’s 50- and 100-watt heads had become the standard for distorted hard rock guitar tone. The problem was that these amps could only achieve those desirable tones with the volume turned up to excruciating levels.

The introduction of the 100-watt Marshall 2203 and 50-watt Marshall 2204 heads featuring master volume controls provided a very attractive solution to this dilemma.

Although the quality of the distorted tone wasn’t quite the same as that of a fully cranked non-master volume Marshall, it still sounded very good and some players even preferred it. Hard rock got a lot crunchier and grittier during the late ’70s, and these Marshall master volume amps played a big role in that.

Solid-State Survivors

Solid-state amps had a bad reputation during the ’70s mainly due to the failures of early models developed by Fender, Standel and a few other companies during the ’60s. However, amp engineers persevered and by the ’70s a variety of solid-state amps that actually sounded good made their way to the market.

The Roland JC-120 came out in 1975 and still remains in production today. Its crystalline clean tone and hypnotic “stereo” chorus effects set a standard for solid-state tone that no competitor has ever really matched

Standouts from this period include Gibson/Norlin’s Lab Series, which Dan Pearce designed with help from synth pioneer Bob Moog (who also developed the active electronics for Gibson’s RD guitars and various Maestro pedals). A Lab Series L5 became B.B. King’s amp of choice from the late ’70s though the end of his career, and a Lab Series was Elliot Easton’s main amp on the Cars’ debut album.

The Roland JC-120 came out in 1975 and still remains in production today. Its crystalline clean tone and hypnotic “stereo” chorus effects set a standard for solid-state tone that no competitor has ever really matched. Another noteworthy solid-state amp from the ’70s is the Acoustic 270, which was used by Frank Zappa and Pete Townshend.

Pignose 7-100

Although walls of stacked amplifiers ruled the concert stage during the ’70s, many guitarists used much smaller amps in the recording studio. One favorite secret weapon during this period was the tiny Pignose 7-100, powered by six AA batteries and delivering five watts of output to its five-inch speaker.

The Pignose can be heard on classic tunes that include Joe Walsh’s Rocky Mountain Way and Eric Clapton’s Motherless Children, and Michael Schenker prominently used a Pignose to record crunchy rhythm tracks and brassy, horn-like lead tones on several of UFO’s late-’70s albums.

Effects

Pedal Mania

Some cool stuff was happening during the ’70s in guitar and amp design, but the real action was taking place in the realm of stomp box effects.

Whereas pedal effects during the ’60s were mostly limited to fuzz boxes, treble boosters, wah pedals and the Uni-Vibe, a vast new range of effects became available during the ’70s, including phase shifters, flangers, chorus, analog delay, compression, EQ, envelope filters, octave dividers, ring modulators and more.

Dozens of new companies dedicated to building effects devices were established during this period, which greatly expanded the growth of the musical instrument industry.

Leading companies from this period included Coloursound, DOD, Electro-Harmonix, Foxx, Ibanez, Maestro, Morley, Mu-Tron, MXR, Roland/Boss, Ross, Seamoon-A/DA and Tycobrahe.

There are too many standouts to list completely here, but products of note include distortion boxes like the EHX Big Muff Pi and MXR Distortion +, early flangers (A/DA, MXR and EHX Electric Mistress), the Mu-Tron III envelope filter and mammoth Bi-Phase, the Boss CE-1 and CE-2 Chorus and the first Boss compact pedals (OD-1 Overdrive, PH-1 Phaser and SP-1 Spectrum), the MXR Phase 90 and Dyna Comp, Foxx Tone Machine... too much good stuff.

Talk Ain’t Cheap

Any discussion of guitar effects during the ’70s would be remiss to omit the talk box. The sound of guitarists bleating and barfing through their talk box tubes was heard on countless hits during this era, from Joe Walsh’s Rocky Mountain Way in 1973 through Jeff Beck’s She’s a Woman, Frampton Comes Alive!, Aerosmith’s Sweet Emotion and Nazareth’s Hair of the Dog in the mid ’70s, full circle to Joe Walsh with the Eagles on Those Shoes in 1979.

Devices like Kustom’s “The Bag,” the Heil Talk Box, Dean Markley Voice Box and Electro-Harmonix Golden Throat made this effect accessible to the masses, but it didn’t really catch on beyond professional stages and studios due to the complex setup and requisite commitment.

Tape Echo

Stand-alone tape echo units were available throughout the ’60s, but the effect really didn’t catch on until the ’70s as the capabilities of units produced then had greatly expanded. The game-changer was the Maestro EP-3 Echoplex, a solid-state unit that offered a sound-on-sound mode that provided cool looping and layering effects, such as the effects created by Brian May on Queen’s Brighton Rock. The EP-3 was relatively road-worthy and reliable, and soon it became a fixture in many performing guitarists’ rigs.

Roland offered worthy competition to the Echoplex with its Space Echo series tape delay units. Many players found the sound quality of the Space Echo delay effects more refined and polished, and Space Echo models with built-in reverb became a de rigueur studio tool for dub producers in Jamaica. The Space Echo can also create trippy psychedelic pitch bend effects when the speed control is manipulated.

EBow

In 1976 Heet Sound introduced the EBow, an unusual hand-held magnetic string driver that produces infinite string vibration (at least until the battery wears down or the user’s wrist goes numb) to mimic bowed strings, horns, woodwinds, synths, elephants, seagulls and angry wives.

In some ways it’s an instrument all unto itself, which explains why Heet Sound never stopped making the things. The EBow is a cheap, fun and creatively inspiring device – something that all guitarists can use more often than not. Buck Dharma used one on (Don’t Fear) The Reaper, and you really can’t get more ’70s than that without a mustache and white satin jumpsuit.

Accessories

Replacement Pickups

One of guitarists’ biggest beefs about guitars made by Fender and Gibson during the ’70s was that the pickups either didn’t have the sonic richness and expressiveness of vintage pickups or the output was too weak.

DiMarzio was one of the first companies to address this concern by offering their vintage-voiced PAF and high-output Super Distortion humbuckers and Fat Strat, SDS-1 and Pre-BS Tele single coils. Seymour Duncan made pickups for Mighty Mite before setting up shop under his own name, and Bill Lawrence made pickups that were used by Joe Perry and Brad Whitford with Aerosmith.

Red Rhodes’ Velvet Hammer pickups also enjoyed a devoted cult following. These pickups offered an inexpensive and effective means for significantly improving a guitar’s tone, something guitarists truly needed during the ’70s.

Strobe Tuners

In this day and age where one can download a chromatic tuner for free as a phone app, it’s hard to imagine how guitarists coped with primitive devices like tuning forks and pitch pipes to tune their instruments. Strobe tuners existed before the ’70s, but they were bulky, expensive tube-driven beasts that weren’t especially convenient for bands playing at Mom’s Beer and Boobs Emporium.

Compact strobe tuners like the Conn StroboTuner ST-11 and Peterson Model 420 (heyyy, maaaan!) may have still been a bit too costly for the average garage band, but they quickly proliferated in recording studios and touring rigs, paving the way for affordable tuners that emerged during the ’80s.