A small group of parents attends a conference where they're educated about the threats to American morality embedded in modern education. There they obtain a list of books believed to present a clear and present danger to young people. They bring that list to a meeting of the local school board. It turns out that 11 of the titles are found in school district libraries or curricula.

Alarmed, school board members direct the superintendent to remove the books and to put out a press statement declaring the tomes "anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Sem[i]tic, and just plain filthy." The board says, "It is our duty, our moral obligation, to protect the children in our schools from this moral danger as surely as from physical and medical dangers."

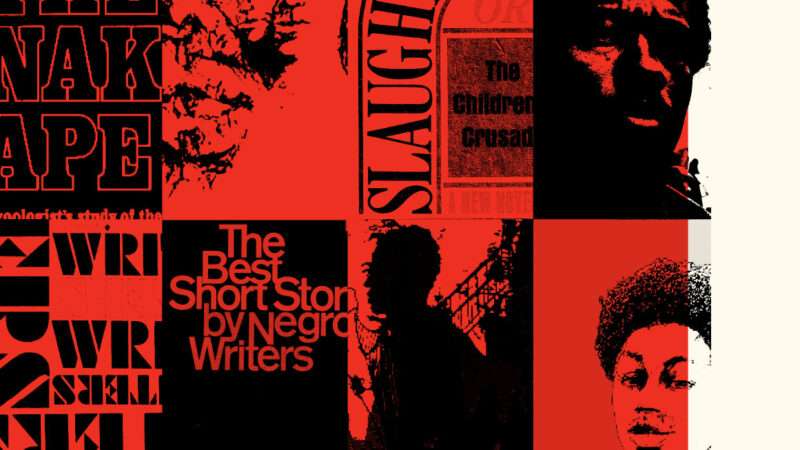

A book review committee is formed, and it recommends retaining most of the books. But the school board disagrees. Nine of the books are removed: Slaughterhouse-Five, by Kurt Vonnegut; The Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris; Down These Mean Streets, by Piri Thomas; Best Short Stories of Negro Writers, edited by Langston Hughes; Go Ask Alice, of anonymous authorship; A Hero Ain't Nothin' but A Sandwich, by Alice Childress; A Reader for Writers, edited by Jerome Archer; The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud; and Soul On Ice, by Eldridge Cleaver.

Did this happen in Texas in 2022? No: The year is 1976, and the place is the Island Trees Union Free School District on Long Island, New York. These events formed the core of Island Trees School District v. Pico, a quirky and mostly forgotten Supreme Court case that is suddenly relevant once again. That relevance is related less to legal precedent than to a powerful moral argument that a plurality of the court made in its dicta. That moral argument should guide our disputes about books in schools today.

Those disputes have been metastasizing. In April, the free speech advocacy group PEN America issued a report detailing 1,586 instances of individual books being "banned" between July 1, 2021, and March 31, 2022, affecting 1,145 unique book titles. By bans, they mean "removals of books from school libraries, prohibitions in classrooms, or both, as well as books banned from circulation during investigations resulting from challenges from parents, educators, administrators, board members, or responses to laws passed by legislatures."

There are easy ways of looking at this issue, and there are hard ways. The easy ways are wrong. The hardest way is right. Let's take each in turn.

The easy ways take a look at the complex and often competing interests at play and simply declare a winner. In one view, parents have an unquestioned interest in governing their child's education, so the parents' desires should triumph. This is, increasingly, the position of the Republican Party. It's repositioning itself as a "parent's party," and when push comes to shove, parents win.

In another view, educators ask: Which parents should win? Is a majoritarian education a quality education? Is parent-driven public education truly even majoritarian? Isn't the sad reality that school board politics is mainly activist politics, driven more by anger and reaction than by calm and thoughtful reflection? We train educators for a reason, they say. Let teachers teach.

A third line of thinking takes a pox-on-both-your-houses approach. Don't choose between public school parents and public school educators. Blow up the system. Pass backpack funding. Expand school choice. That way, parents win and teachers win. Parents can find the school that meets their standards of excellence and/or teaches their values. Educators can build institutions centered around their expertise. Families will then choose from a menu, and that menu will cover almost every educational meal.

I'm drawn to the third way. School choice de-escalates curricular culture battles and enhances the autonomy and responsibility of every individual in the system. Both parents and teachers have the ability to vote with their feet, to seek schools and jobs that match their philosophy and priorities. Moreover, it builds a sense of constructive cultural purpose. An explosion of school choice could revitalize the lost art of institution-building and community formation.

But even the third way—the better way—isn't enough. It is both contingent and distant.

Don't get me wrong: The school choice movement (including homeschoolers and charter schools) has made immense progress. Homeschooling barely existed 50 years ago, but by the 2020–2021 school year roughly 3.7 million students were educated at home. Charter schools educate more than 3 million students a year, and in 2018 a half-million students were enrolled in private school choice programs. But that still leaves roughly 50 million students in conventional public schools. Until most families actually have backpack funding, we must deal with the world as it is, and that world is going to educate the vast majority of American students in conventional public schools for the indefinite future. What do we owe them as long as they're there?

That brings us back to Pico. A collection of students sued the Island Trees school district, arguing that the board's book removal order violated the students' First Amendment rights to receive information. In other words, in the fight between parents and teachers, the students should have a constitutional say too.

The Supreme Court agreed, but its plurality opinion created almost as many questions as answers. It left intact broad state authority over school curricula, and it excluded from the scope of the decision the acquisition of library books. It merely tried to answer whether, sometimes, removing a book from a school library could violate the First Amendment.

The answer was yes. The justices argued that the First Amendment includes a "right to receive ideas" that is "a necessary predicate to the recipient's meaningful exercise of his own rights of speech, press, and political freedom." This right meant that schools did not have "unfettered discretion" to remove books from shelves. At the same time, the plurality held that "we do not deny that local school boards have a substantial legitimate role to play in the determination of school library content."

How does a school board square that circle? What are the limits of its "legitimate role"? Here was the essential holding: "Petitioners rightly possess significant discretion to determine the content of their school libraries. But that discretion may not be exercised in a narrowly partisan or political manner. If a Democratic school board, motivated by party affiliation, ordered the removal of all books written by or in favor of Republicans, few would doubt that the order violated the constitutional rights of the students denied access to those books. The same conclusion would surely apply if an all-white school board, motivated by racial animus, decided to remove all books authored by blacks or advocating racial equality and integration. Our Constitution does not permit the official suppression of ideas."

Is that a clear standard? Well, no. It's the judicial equivalent of declaring, "Just don't go too far." And how far is too far? Defining the extremes (no books by Republicans, no books by black authors) doesn't define the line. Indeed, the case was ultimately so unhelpful in drawing meaningful lines that there's real doubt the plurality opinion would hold in the current Court.

As a statement of legal principle, Pico is unhelpful. But as a statement of educational philosophy, Pico shines. It provides a prudential standard that should help school boards navigate the complexities of parent complaints and students' educational interests. That standard is rooted in the Court's description of the nature of students' rights and the purposes of American education itself.

In the Pico ruling, the Court quoted its earlier judgment in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969): "In our system, students may not be regarded as closed-circuit recipients of only that which the State chooses to communicate….School officials cannot suppress 'expressions of feeling with which they do not wish to contend.'" The Court added in Pico: "In sum, just as access to ideas makes it possible for citizens generally to exercise their rights of free speech and press in a meaningful manner, such access prepares students for active and effective participation in the pluralistic, often contentious society in which they will soon be adult members."

In those sentences, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. perfectly captured the problem with book bans. No, it's not that any given book should be on the shelves. There are, for example, books that are either too explicit for young children or explicit enough that they should be viewed and checked out only with parental permission. It's that book bans inhibit a core function of public education. They teach students that they should be protected from offensive ideas rather than how to engage and grapple with concepts they may not like.

To borrow a phrase from Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, book bans are part of unlearning liberty. The process of American education is inseparable from the process of building American citizens, whether those citizens are educated in private schools, home schools, or public schools. It's sometimes tempting to try to avoid cultural conflicts by asking schools to stick to the basics, such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. But one of those "basics" is preparing young people for "active and effective participation" in American pluralism.

As a practical matter, that means that book removal should be a last resort, both because limiting access to content can implicate students' ability to receive ideas and because of the message of the removal itself. It teaches a lesson—that the response to a challenging thought is to challenge the expression itself rather than the idea.

That does not mean that anything goes. As a matter of common sense, elementary school libraries should have different standards from high schools. And some books are so graphic that parents should have a say in whether even their older child can check them out.

But the bottom line remains. When school boards and principals hear challenges to books or consider restrictions on curriculum, they need to understand the very purpose of their educational project. It is not, as the Island Trees district declared back in 1976, to protect children from "moral danger." It is to prepare citizens for pluralism. Our nation's schools must not suppress "expressions of feeling with which they do not wish to contend."

American students are being taught that speech is dangerous. They are learning that the proper response to an offensive idea is to ban the idea and punish the speaker. And who taught them these lessons? Both the parents who sought to protect their children and the educators who forgot their central purpose.

The post The Dangerous Lesson of Book Bans in Public School Libraries appeared first on Reason.com.