In the mid 1960s, the American actress Joan Copeland was finding it increasingly difficult to secure parts. One day, though, she was up for a major television role and met with the writer, producer and sponsor. They were enthusiastic. Rehearsals were planned.

Then she was asked if she was related to the playwright Arthur Miller. She confessed that he was her brother. She never heard from them again. Copeland was not alone. Other actors, directors and producers found themselves blacklisted, alongside others from Broadway and Hollywood, who had been members of the communist party in the 1930s and 1940s, or espoused radical causes.

Meanwhile, people were summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) or its Senate equivalent. The latter was chaired by a junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy. There, they were required to confess to their “sins” and to name others who had been party members.

During the second world war, the Soviet Union had been an ally to the United States. After the war, however, it was seen as the enemy. In August 1949, four years after Hiroshima, the then USSR exploded an atom bomb at a remote test site in Kazakhstan.

A year later, McCarthy claimed to have a list of 205 state department employees who were “known communists”. US president Dwight D. Eisenhower failed to denounce him and, indeed, supported legislation which facilitated investigations into communist activities. Two spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were unearthed (he, it later transpired, guilty, she not) and executed.

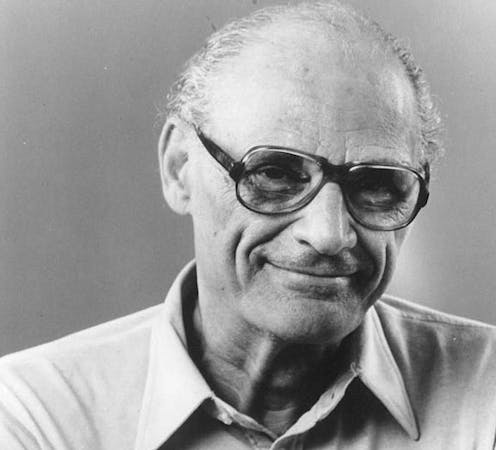

Arthur Miller’s inspiration

Miller watched on as those he admired were named. Lee J. Cobb, who had played protagonist Willy Loman in the original production of Miller’s Death of a Salesman, held out for two years, but finally capitulated and offered up names for fear his career would end – as the careers of many writers, actors and singers did.

In response, Miller decided to investigate writing a play about an earlier witch hunt, which had occurred in Massachusetts in 1692. Before setting out to look through records in Salem, however, he was called by his friend, Elia Kazan, the director of Death of a Salesman.

He went to meet him in his nearby home, only to be told that he had decided to name names, as had Clifford Odets, the playwright who Miller had most admired.

On his return from Salem, Miller turned on his car radio and heard the names Kazan had offered in a supposedly secret hearing, just as the names of those who were supposedly witches in Salem had been read out in the court. Ten years passed before Miller could bring himself to speak to Kazan again.

Miller wrote The Crucible with a sense of urgency. Two of his central themes – betrayal and guilt – were braided together in a play which reflected his belief (underscored, for him, by the Holocaust) that civilisation is fragile.

He was writing, Miller told me, at the “edge of a cliff”.

Miller also confessed to me that he was not prepared for the hostility with which the play would be received. As the audience realised that they were being invited to see a parallel between the events of 1692 Salem and the Hollywood witch hunt then being played out in contemporary America, in his words, they froze.

Standing in the lobby as they left, he was ignored by those he had thought his friends. Actor Madeleine Sherwood, who played Abigail Williams, had a similar experience.

The Crucible’s legacy

The Crucible went on to be Miller’s most produced work. The central character, John Proctor, believes it is possible to declare his own separate peace, as others are swept up by moral anarchy masquerading as justice. But he comes to understand that no man is an island.

The play, it seems, could be reinvented in every country at every time. In China, it was seen as a comment on the Cultural Revolution, in which the young gained power over the old. Its portrait of a man who marches to a different drummer, who resists the power of the state to define reality, found parallels around the world.

Miller was not called before the HUAC himself until 1956 and then largely because of his relationship with Marilyn Monroe, as the committee was desperate for publicity. He refused to name names and was cited for Contempt of Congress, sentenced to prison and fined, though this was reversed on appeal.

In 1999, Elia Kazan was awarded a lifetime achievement Oscar. The theatre was picketed by many of those who had been blacklisted. Inside, some refused to stand or clap. Miller, though, supported him. The fault, he insisted, lay not with Kazan, but with those who put him and others in a position where betrayal seemed an option.

Christopher Bigsby has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.