Ping! An invitation has landed in your work inbox (is it really an invitation if attendance is compulsory, though?) The subject: “Office team-building away day!” What follows is a packed itinerary mixing jollity and hardcore business strategy. Your morning call time is 7.30am, when you’re expected to be at the station for the first train out of the city, and you won’t return until at least 12 hours later (overnight trips appear to have been vetoed, a decision that may or may not be linked to the mutterings you’ve overheard in the communal kitchen about “what happened last time”).

If you’ve had an office job over the course of, say, the past two decades, it’s pretty likely that you have received an email much like this one. Team building has become a mainstay of our modern working life; you might embark on such sessions annually, twice yearly or even monthly, depending on your HR team’s zealousness. In theory, these sessions can build morale, strengthen bonds between colleagues and help workers feel more valued, as well as allow them to think about their work in a different way.

However, when it comes to away days, retreats and group bonding, the corporate world seems to be divided into two very vocal camps. There are those who thrill at the idea of, say, spending the afternoon in an escape room with a motley crew of office characters, or racing their work nemesis through an inflatable assault course. And then there are those who are chilled to the bone by the words “icebreaker game” – the ones who can’t imagine anything worse than having to come up with two truths and a falsehood for a lo-fi version of Would I Lie to You?, with Keith from senior management in the Rob Brydon role.

When YouGov surveyed Brits about their attitude to team building in 2022, the results were predictably mixed. While 44 per cent of participants said that these exercises had helped their group work together better, 50 per cent disagreed. Some 60 per cent said that they had found the experience “embarrassing or cringe-worthy”. And anecdotally at least, it seems to be those episodes that stick in our memory and potentially colour our attitudes. One colleague has been put off the whole thing ever since she went on a boat trip with former co-workers, run by a shouting man who seemed better suited to running a boot camp. As they approached the dock, he yelled for her to “quick, get out!” – “so I just lost my head and jumped out of the boat into the Thames, fully dressed”.

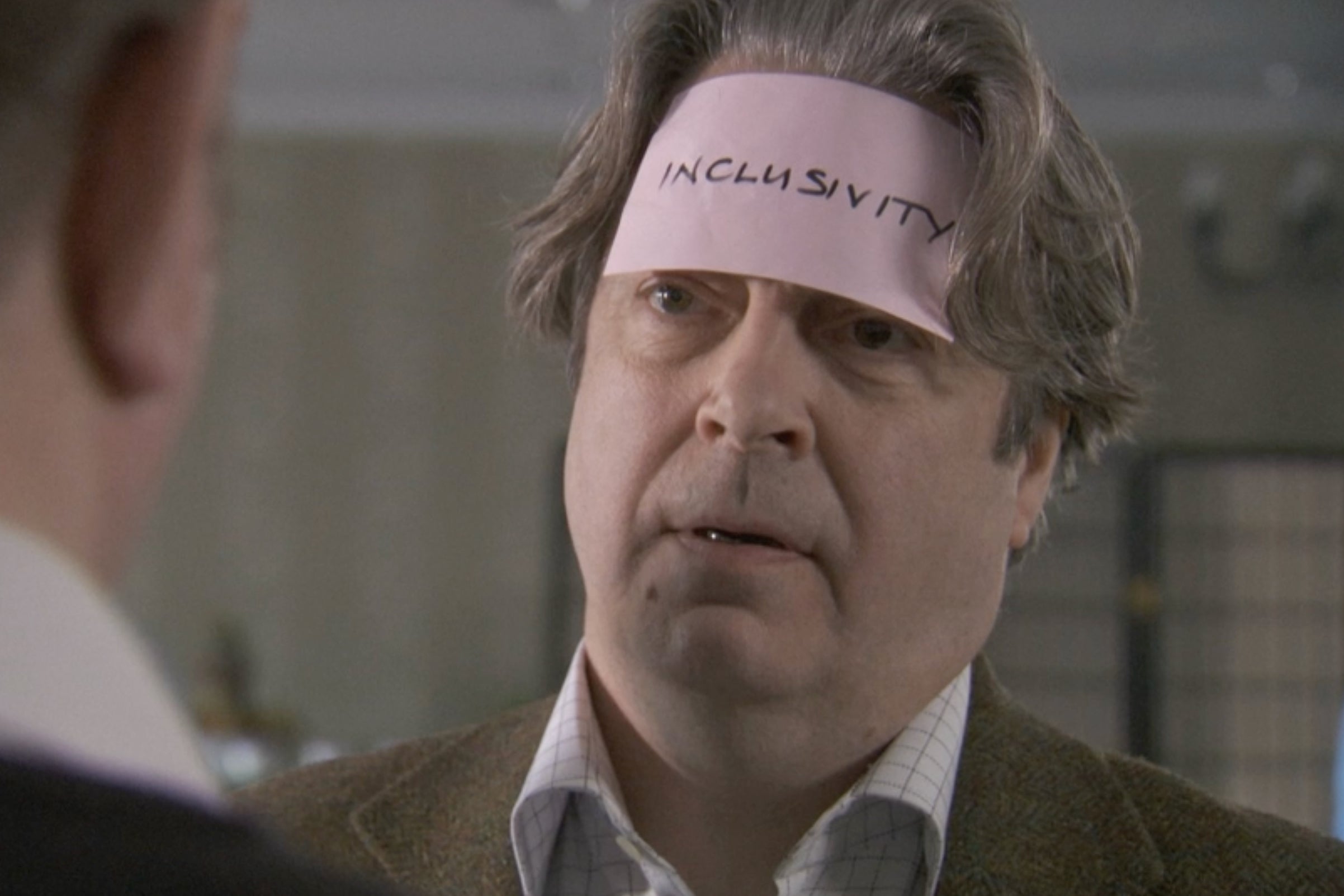

In fact, getting soggy appears to be a strange commonality. There are countless tales of raft-building gone comically awry and face-planting in muddy assault courses. Emma Elms, journalist and founder of Sparkle and Dust Fashion, recalls how she and her colleagues headed to the seaside and were tasked with making an advertising video for their glossy magazine (very Apprentice). “My team of six got very carried away and my boss asked me to don a Bridgerton-style period costume, get in the sea, then be lifted out of the water by our finance guy, as if we were having the romance of the century. I obediently went ahead and allowed myself to be dunked in the sea… Even worse, it was a very boozy trip away, so my main memory is that, as he ‘rescued’ me, our finance man oozed alcohol fumes from every pore.” Then there are the more banal tropes, such as having to stand in a circle, catch a ball from your colleague and come up with a “big idea” (as illustrated in a particularly toe-curling episode of The Thick of It, when an MP and his advisors head off to a “Thought Camp”).

So how did the workplace equivalent of a stag or hen do – often involving organised fun, a group of people you probably wouldn’t normally socialise with and, sometimes, more alcohol than strictly necessary – become so commonplace? The emphasis on encouraging goodwill between teams can be traced back to a series of experiments carried out at the Western Electric factory in Hawthorne, Illinois in the Twenties and Thirties, known as the Hawthorne studies. Researchers changed certain conditions to see how they impacted productivity: they tweaked the factory lighting, altered working hours, and amended how they consulted with employees – as well as how they were supervised. The conclusion? That the practical changes were less impactful than the more psychological ones: when the workers felt more valued by their bosses and took pride in their collective achievements, they actually performed better.

Later, after the Second World War, the sense of military-style camaraderie began to permeate our ideas about work. “There was that ‘brothers in arms’ element that people started to want to replicate,” says Charlie Sampson, executive director of leadership development at employee engagement consultancy scarlettabbott. Then, in the Sixties, concepts like personality profiling – quizzing employees on their temperament with the aim of better understanding how they’d work in a group – became popular. From the Eighties onwards, we see team building emerge as an industry of its own. “It was almost like, ‘We should be doing this, because everybody else is doing it,” Sampson says. It’s around this point that “a lot of what people associate with the ‘dark side’ of team building, very much the things like raft-building and making stuff out of toilet rolls” start to crop up.

The industry, Sampson adds, has certainly “evolved since then” but is still “relatively in its infancy in terms of the skill and the structure and the approach that people take”. Often, you can break a team-building plan into two parts: “You have the emotive elements, so that’s things like building trust, vulnerability, openness, connection, the human elements. And then you have the cognitive elements, things like problem-solving, strategising, product development”.

One of the main mistakes made by bosses is that “they’re not clear on what we’re trying to develop here. Is it both? Is it one? Is it the other?” The end result is often a jumble that might be enjoyable in the moment, but is unlikely to actually do much long term. Another pitfall? Seeing team building as something that is done to a team, rather than with them: think of David Brent forcing his long-suffering colleagues to listen to his guitar playing in The Office. “They’ll say, ‘Right, we need to get together,’ and what often happens is they will suggest something that they like doing.” Sampson recalls one example of “a CEO who was a big fan of sailing”, so took his colleagues on a day out to sample his favourite activity. “Most of the team spent the whole day being seasick.”

The question to ask is: what, if anything, will be different as a result of doing this thing?

Often, too, there’s no sense of clarity for those taking part about why exactly this is happening. Why am I constructing a bridge from spaghetti? Why do my colleagues and I appear to have wandered onto the set of SAS: Who Dares Wins, complete with yelling instructors? Many activities, Sampson notes, take ideas and concepts from the military or professional sport. “Say you were in a rugby team, there’s a physical risk to yourself if your team doesn’t do their job. It’s obviously the same in the army. That doesn’t translate very well into the corporate world, because most of us in our jobs are not physically threatened. I think you’ve got to be very clear, if you’re borrowing from those worlds, about what’s the bit that’s useful and why are you doing it with the team?”

Leadership coach Jacqui Jagger, co-founder of Catalyst Careers, agrees that sometimes, the bigger message can get drowned out by noisy concepts. Quite literally, in fact. She can remember organising a leadership conference early in her career when she and her co-workers decided to put on a session with a steel band. “The whole point of it was that [attendees] worked individually on their own part of the overall piece,” she explains. Then, when they reunited to play a song, they’d realise what they could achieve when everyone did their allotted task. “But when people look back, they aren’t going to remember the message. They can remember having a ball of an afternoon – or thinking, ‘Christ on a bike, I’m at a conference, why am I being asked to play a steel drum?’” Since then, Jagger notes, she’s learned that the budget required for a splashy activity might be better invested on the basics such as “training, development, and support for leaders and managers” – because even if you have a great day, “If you then put those people back into a workplace with leadership that’s unskilled, it’s not going to be sustainable. It’s not going to last.”

So how can bosses and workers alike make sure that their next team-building jaunt is actually useful? “The question to ask is: what, if anything, will be different as a result of doing this thing?” says Sampson. “Whether it’s a day out, whether it’s something virtual, can you answer that question: what is the output of this and why are we doing it?” When he’s worked with groups as an external organiser, he has found it useful to have brief chats with the staff who will be taking part, to better gauge the dynamic and any underlying tensions, and then feed that back to the boss. “It comes back to [the leader’s] awareness and honesty as to whether they want to confront what could be some very difficult things. Not everybody wants to.”

This approach can help deal with the cynics, too. “I don’t think I’ve ever done a team intervention where there haven’t been cynical people in the room,” Sampson says. “I think the most important thing is to acknowledge the cynicism … just by saying to somebody: what have you done that was a complete waste of time [or] have you done something that you found helpful?” The aim, he adds, is to “place the psychological ownership” for the whole thing “with the team, rather than it being the boss’s job or something that’s done to them”. Maybe it’s time to start putting our scepticism to one side. Just please don’t make me play the steel drums.