When local bureaucrats in Hennepin County, Minnesota, seized an elderly woman's home over a small tax debt, sold it, and kept the profit, they likely had no idea they would set in motion a series of events that would cripple the practice known as "home equity theft" across the country.

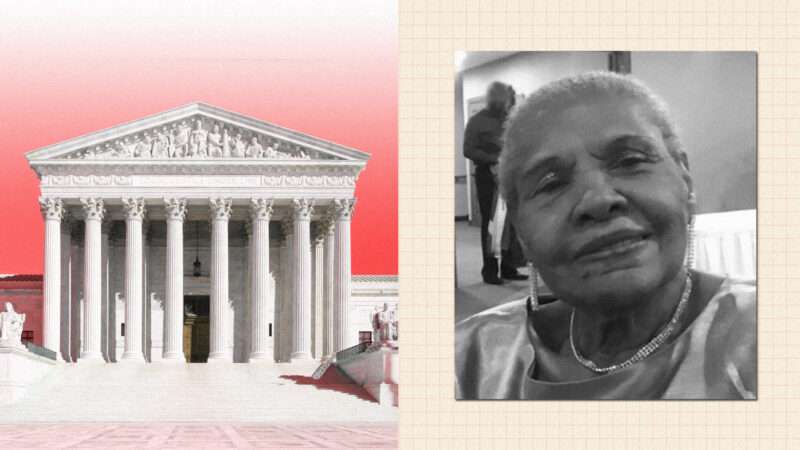

Yet that's what happened. The Supreme Court on Thursday unanimously ruled that the government violated the Constitution when it took possession of Geraldine Tyler's condo over an overdue property tax bill, auctioned the home, and pocketed the proceeds in excess of what she actually owed.

Tyler, who is now 94 years old, purchased the Minneapolis-area condo in 1999. But a series of events, including a neighborhood shooting, prompted her to relocate to a retirement community in 2010, at which point it became difficult for her to pay both her new rent and the property taxes on her former home. She accrued a $2,300 tax bill, which turned into an approximately $15,000 bill after the government added on $13,000 in penalties, interest, and fees. Local officials then sold the home for $40,000—and kept the remaining $25,000.

Tyler spent years arguing that such a taking was unconstitutional. But despite the case appearing fairly black and white from the outset, she had no such luck in the lower courts. When her case went before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit, its ruling was also unanimous—in favor of the government. "Where state law recognizes no property interest in surplus proceeds from a tax foreclosure-sale conducted after adequate notice to the owner, there is no unconstitutional taking," wrote Judge Steven Colloton.

The Supreme Court forcefully overturned that decision today. "A taxpayer who loses her $40,000 house to the State to fulfill a $15,000 tax debt has made a far greater contribution to the public fisc than she owed," wrote Chief Justice John Roberts for the Court. "The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar's, but no more."

At the heart of the case is the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment, which stipulates that "private property [shall not] be taken for public use without just compensation." In explaining the justices' decision, Roberts traced the spirit of the law back to the Magna Carta, then to English law, and ultimately to the States, buttressed by several Supreme Court precedents which, as Roberts wrote, "have also recognized the principle that a taxpayer is entitled to the surplus in excess of the debt owed."

Tyler is far from the only victim of this practice. Home equity theft is legal in Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Dakota, and the District of Columbia, although today's ruling should hamstring those forfeiture schemes.

How home equity theft has been executed across those states varies widely, although the life-wrecking consequences remain consistent. In Nebraska, for example, local governments sell tax debt to private investors behind a homeowner's back. The homeowner eventually receives a letter, after three years have gone by, giving them 90 days to satisfy the full tax burden, which has continued accruing over those three years, along with 14 percent interest and additional fees. Over those three years, the debtor does not receive notification from the government of his ballooning debt, as the private investor quietly continues satisfying it.

In 2013, for example, Kevin Fair of Scottsbluff, Nebraska, quit his job to become the full-time caretaker to his wife, Terry, who had been diagnosed with a debilitating form of multiple sclerosis. Without a steady source of income other than Social Security, he fell $588 behind on his property taxes. When he finally received notice from Continental Resources, the private investor that covertly bought out his debt, he could not afford the total, which came out to $5,268.

His house, however, is worth $60,000, and Continental Resources told him it intended to take the whole shebang. "In Nebraska…people are shocked about how the law actually operates," Jennifer Gaughan, chief of legal strategy at Legal Aid of Nebraska, told me in January. "It's usually elderly people…people who own their homes outright who don't have a mortgage, and there's usually some kind of intervening situation." In Kevin Fair's case, it was his wife's illness. She has since died.

Prior to oral arguments before the Supreme Court last month, a cross-ideological coalition of organizations assembled in favor of Tyler. Few things are transpartisan these days. But it took a 94-year-old woman and a nearly 10-year crusade to establish the obvious: that the government should not be able to steal home equity from its own citizens.

The post The County Sold Her Home Over Unpaid Taxes and Kept the Profit. SCOTUS Wasn't Having It. appeared first on Reason.com.