Commercial and art photography are typically situated in opposition. But for a host of contemporary photographers, the fusion of commercial, editorial and personal work opens a rich dialogue between these seemingly disparate parts. We profile five photographers that have each forged a multifaceted, distinctive career in image-making. For some, this involves maintaining a consistent aesthetic and conceptual approach, whether photographing a luxury car or a stack of papers. Others seek inspiration in the contrast, finding value in both the creative boundaries provided by commercial work and the limitless possibilities of their personal practice. These artists celebrate the power of collaboration, whether learning from the teams that shape commercial projects alongside them, or welcoming art directors into the often-solo pursuit of documentary photography.In branching across traditionally separated formats and regimented methods of working, these photographers discover innovative new ways of making pictures in a world that is already saturated by them.

Mattia Balsamini

Mattia Balsamini began his career assisting David LaChapelle, a photographer who has successfully straddled the commercial, art and celebrity worlds. Since then, Balsamini has worked for commercial brands such as Lamborghini, Valentino and Swatch and collaborated with the likes of MIT and Nasa, while also relishing the chance to develop his own style through editorial commissions. ‘It gives you the opportunity to try new things within your aesthetic. It teaches youto think fast. I really learned how to be a photographer through editorial.’

The objects in Balsamini’s works, whether cars, scientific equipment or tiny watch parts, take on monumental form, flooded with atmospheric shadows and saturated colours. His distinctive visual style runs seamlessly through many of his projects, no matter the client or focus. ‘Commercial work is not just about making money; a lot of us actually want to blend. People who make images are interested in content, shape, the mystery of things. The world is so interesting, it’s all worth being represented.’

His recent book Protege Noctem was co-authored with writer Raffaele Panizza. The pair travelled around the world to speak with scientists and those ‘defending darkness’ by protesting against the excessive use of the artificial light that wreaks havoc on surrounding habitats. This project blended all his obsessions: technology and the way things work; atmosphere; poetry and magic. He enjoyed the limitlessness of the project, which has an environmental focus and has also fed back into his commissioned work. ‘After that book, my commercial work was really shaped by the shadow, the imperfection, those colours,’ he says. ‘These personal projects help you explain to yourself who you are as a photographer. You recentre. And you put everything you’ve learned from commercial work into that.’

Tina Tyrell

Tina Tyrell shoots characterful portraits of well-known faces – Mark Ruffalo striking a saintly pose or Lily Gladstone igniting a flame near her cupped hand – alongside her own experimental pieces, which include found film, documentary photography and staged family shots. For Tyrell, working across the commercial and art worlds means moving between analogue and digital. ‘I’ve been in this bisected headspace forever,’ she says. ‘In high school, I learned with black and white film. This is where I feel most comfortable. Within a few years of becoming an adult and trying to have a career, that all became irrelevant because everything was digital.’ While her editorial images have a very different feel to her personal work, she looks for a sense of human relation across all of it. ‘I love photographing people,’ says Tyrell. ‘I find connection there, and that transcends between practices. When I get a commercial project, it’s usually a celebrity mixed with a fashion brand. But almost always it’s a person, and I can create a story with a person.’

Tyrell continues to work with film for her personal pieces. She is compelled by the archival nature of photography, and is particularly drawn to images that have a timeless feel. Children sometimes feature, captured in a split second through her lens before they change and grow. Her image from a youth climate march, for example, depicts the back of a young woman’s head as she strides forward. Another series was inspired by her discovery, in a West Virginia barn belonging to her relatives, of a box of 4 x 5 Kodak negatives featuring images of the Manhattan townhouse of her husband’s great-grandfather. She printed them and presented them alongside photographs of her own children standing in front of the barn. ‘The more commercial one side of my work is, the more liberated I feel to be as poetic and nonsensical as I want to be on the other,’ she says.

Gabby Laurent

Gabby Laurent’s personal work often focuses on herself as a subject, taking a performative role, tumbling and leaping in front of the camera. Her playful images explore themes of domesticity and motherhood, and she also embraces the physical side of image-making, whether that means framing her C-prints with upholstered fabric or using cut-outs to create striking in-camera effects.

‘My personal work is very singular,’ she says. ‘It’s for me, I don’t do it to please anyone else. It comes from a very unconscious place.’ By contrast, commercial shoots, photographing for the likes of Simone Rocha and Stella McCartney, involve a team working towards the same goal. Despite their divergent process, she finds a through line between the various applications. ‘I do find commercial shoots are quite performance-based,’ says Laurent. ‘There’s a model, there’s make-up. Commercial shoots have to be very convincing, but it is still a performance. As the photographer, you need to understand how to direct that.’

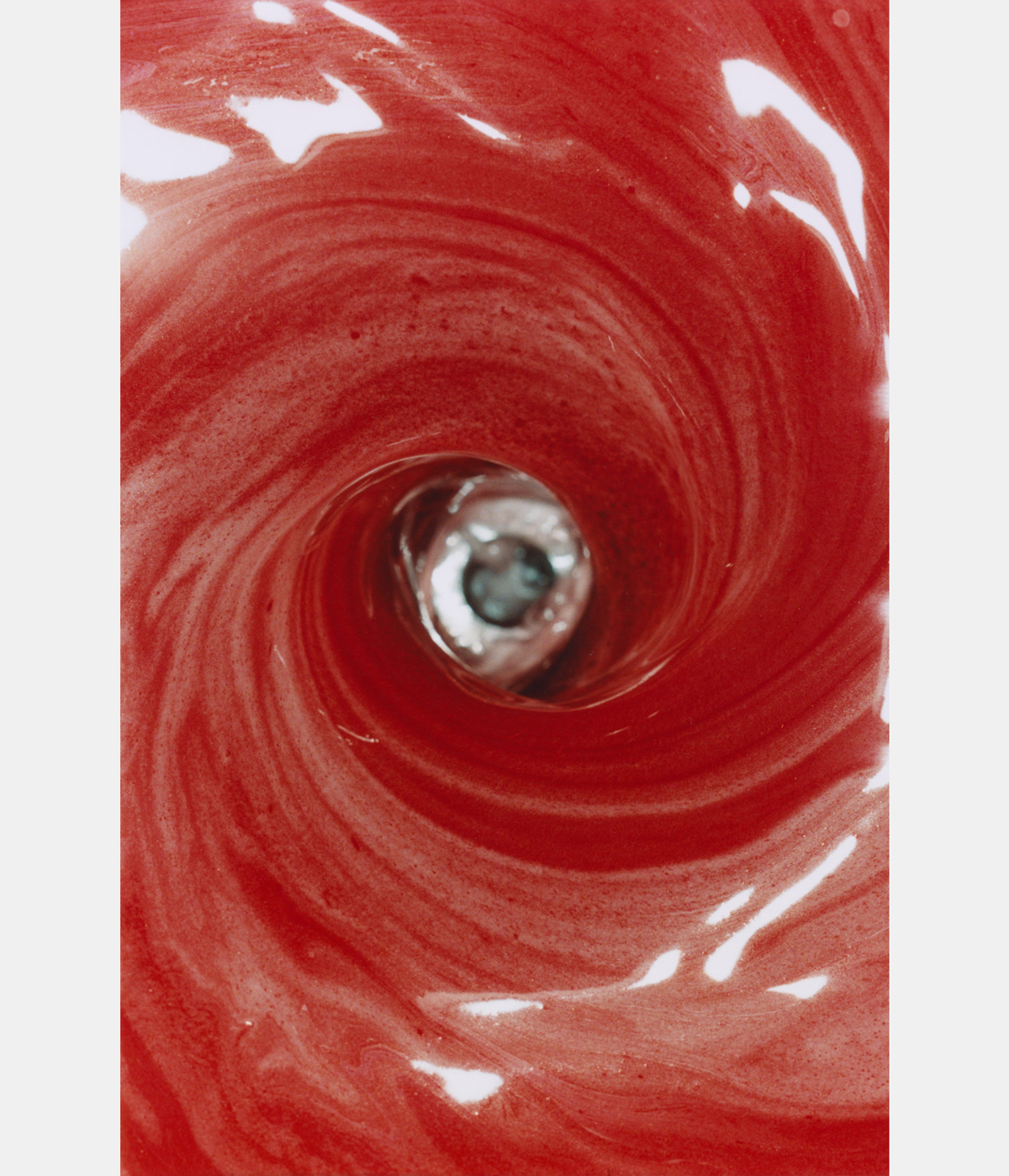

Laurent sometimes collaborates with family members for her personal work. Her unborn child features in some images as a pregnant bump, while her recent ‘Red Whirlpool’ series was created with her daughter. They poured milk, food dye and water down the sink, capturing the surreal swirl as it tumbled down. ‘I love that it was a collaborative piece with her,’ she says.

While her personal work reflects the radical feminists of the 20th century who mixed performance and domesticity, it is also a product of her current experiences. ‘My world at the moment does have a lot of the domestic in it,’ says Laurent. ‘Part of it is a practical issue of when I get to make my own work. Especially when you have children, you take your time when you can get it. This is my internal world at the moment and, very practically, home is where I am a lot of the time.’

Kohei Kawatani

Everyday and luxury items receive similar attention in Kohei Kawatani’s dynamic digital photographs. As an artist, he has won prizes at the Japan Photo Award 2019, and the Kassel Dummy Award 2020 for ‘Tofu-Knife’. This series features items such as rubber gloves, houseplants and stair rails, logged with scientific precision and shot in a manner that conjures up both art objecthood and commerciality. He has also worked for Loewe and cult Japanese confectionery company Unique Human Adventure.

Kawatani enjoys the slippage between high and low culture. ‘Loewe makes such expensive stuff, so you show it the opposite way. The kitsch way,’ he says. ‘I’ve imported the idea of changing value from the art world. Like Duchamp or Warhol, the cheap thing becomes special. I like changing perspectives. I’m not a serious guy! Sometimes it has a concept and sometimes it just looks good.’

Kawatani didn’t study at art school, which he thinks gives him an individual approach. His images feel most at home online, especially on social media, and he has mixed feelings about printing images to sell. ‘The important part for me is making the images. I am very suspicious about selling prints from a digital camera. An edition is like a fake,’ he laughs. Rather than reject this format, he is interested in exploring the meaning of printed digital images, the results of which will be on show at Tokyo gallery Parcel next autumn. Likewise, he welcomes the messily entangled nature of commerce and art, mirroring the reality of our world. ‘Capitalism is getting bigger, and working in the commercial industry gives me a unique perspective on this. Photographers are the only artists who can work so easily from both sides. What is important for clients is changing, and I can learn a lot through their thinking. The trend is for dark or rough images. Maybe it’s reflecting the conflict in the world.’

Kalpesh Lathigra

Kalpesh Lathigra has worked for 30 years as a war photographer and celebrity portraitist. His documentary practice has taken him from Romania to Afghanistan, and he has photographed a host of famous faces, such as Joan Collins, Carey Mulligan and Idris Elba, without the usual glitz and photoshopping, for ‘A Democratic Portrait’. He found a new way of working after meeting Eugenia Skvarska at Central Saint Martins as a guest lecturer for her MA fashion communication studies group. With Skvarska as art director, the pair decided to photograph her native Ukraine. ‘I wasn’t interested in the idea of warfare or conflict in the direct sense,’ says Lathigra. ‘I was interested in Eugenia’s story and her relationship with the country.’

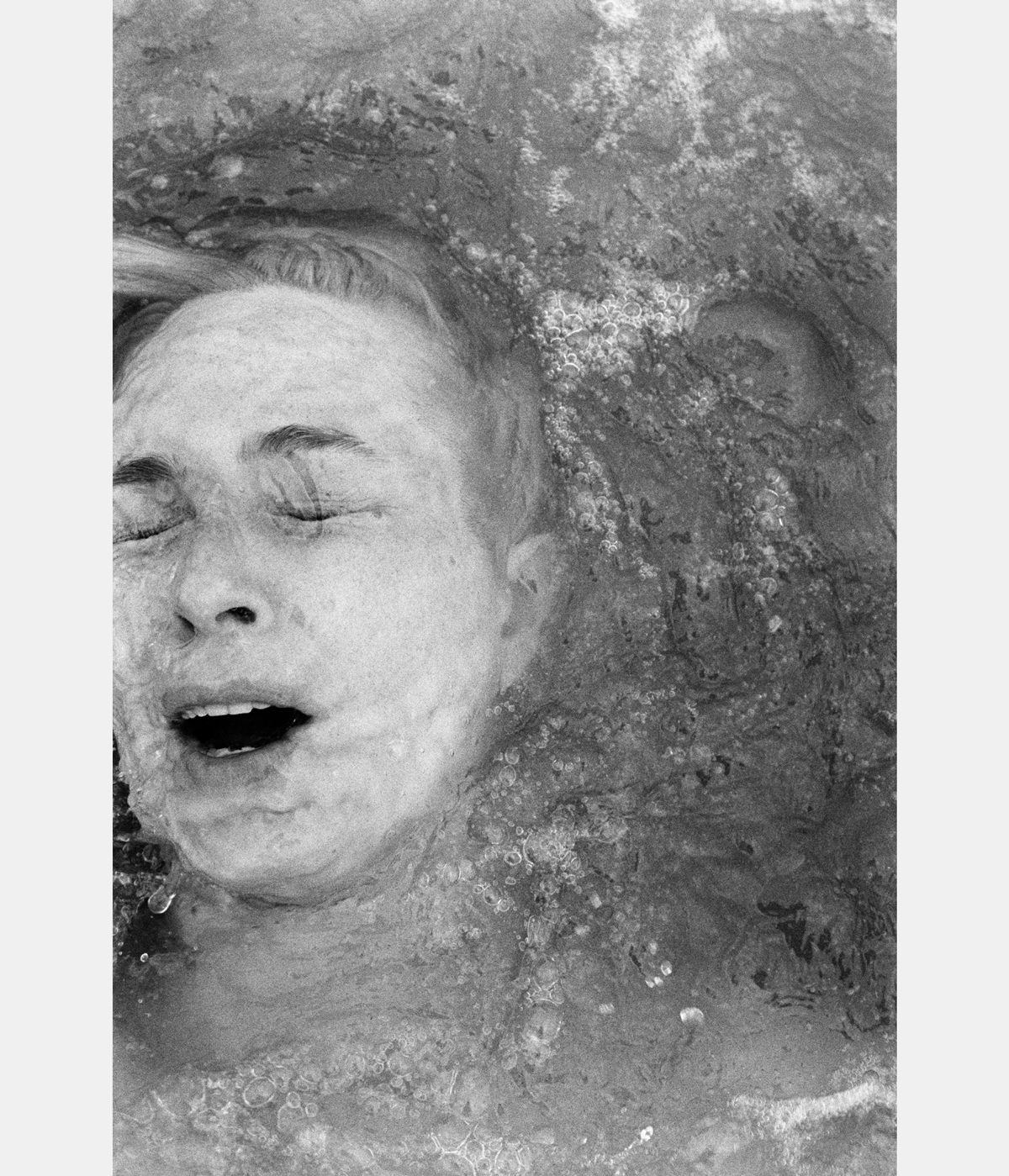

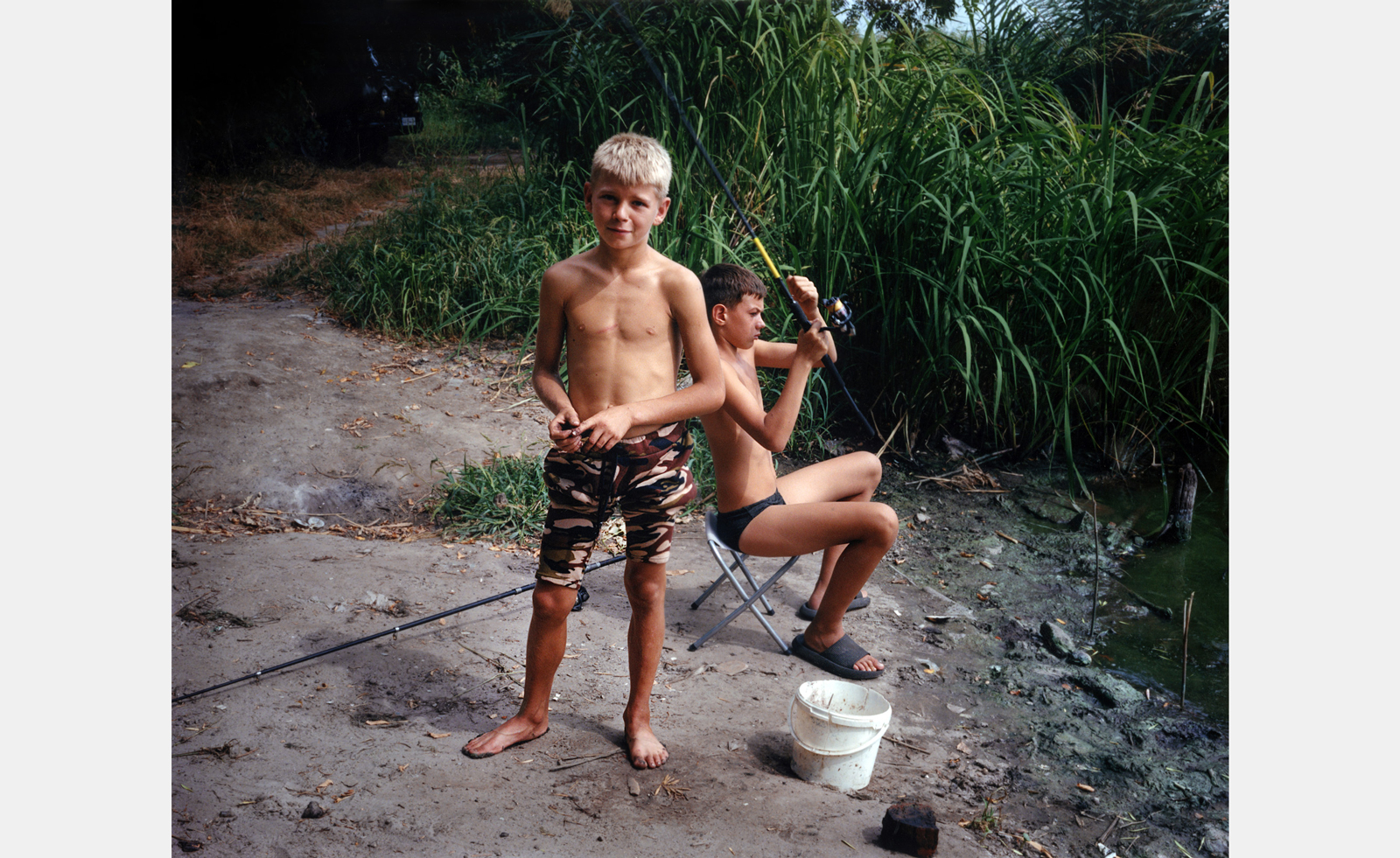

The project is focused around the Dnipro river, which cuts through the centre of the country. ‘You can’t even imagine what’s happening among this beauty,’ says Skvarska, who paused her fashion and art direction practice after Russia’s invasion. ‘Compared to the war, fashion didn’t feel like it mattered.’

It was important for both that they didn’t just show the devastation happening to the country, but also its landscape and people. Partly to combat trauma fatigue that viewers have towards images of ruination, they also wanted to hold together the region’s pain with its hope and history. Lathigra would often zoom out from sites of destruction, showing them instead in the background or off-centre. ‘This is cultural diplomacy,’ says Skvarska. ‘People don’t know anything about Ukrainian culture. Building this story piece by piece, showing the resistance of people who swim in the river during the summer, time with family, is fascinating.’ Lathigra describes this as ultimately Skvarska’s project. ‘There was a time when I’d be globetrotting place to place. It was the idea of the Western gaze. Today we have the tools that people on the ground can tell their own stories.’

A version of this article appears in the January 2025 issue of Wallpaper* , available in print on international newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today