On Sept. 29, 1946, the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League secured a Negro World Series victory by defeating the vaunted Kansas City Monarchs, 3–2. The series had gone to the wire; over seven games the Eagles and the Negro American League’s top team had bounced from New York to Newark, K.C. to Chicago, and back to Newark, trading runs and wins and losses, too. But in the end, Newark prevailed, and for Effa Manley, the team’s co-owner and business manager, the championship was a welcome reward and much-needed validation. Since 1935, Manley and her husband, Abe, had dumped thousands and thousands of dollars into their team while navigating the ups and downs of segregated baseball. Already reveling in the increased profits of the World War II years, courtesy of defense hiring that filled Black fans’ wallets with cash, the championship was but another revenue driver and a sure sign that the team’s fortunes would only climb higher.

Except … they didn’t.

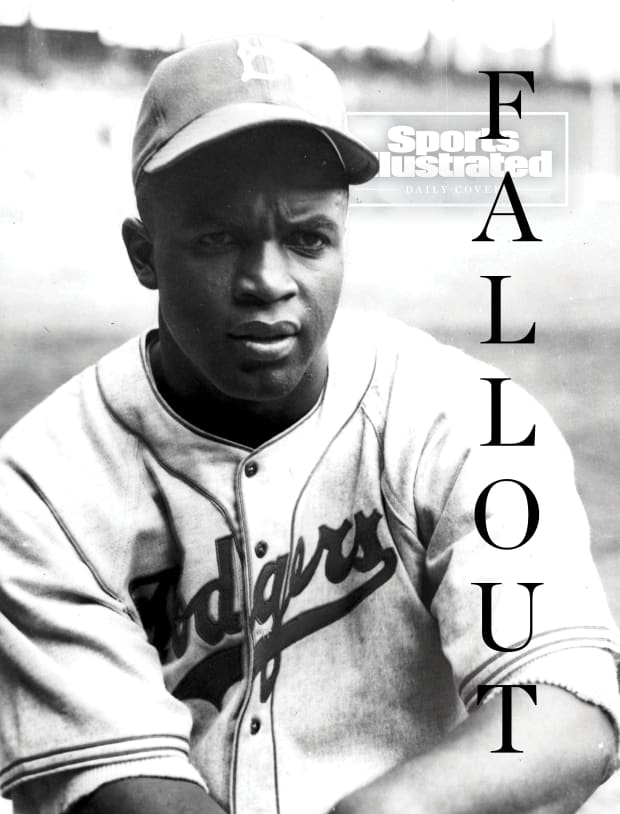

Just five days after the Eagles became the champions of Black baseball, the Montreal Royals of the International League clinched their own championship title by winning the Junior World Series. The Royals, the Triple A affiliate of MLB’s Brooklyn Dodgers, were the last minor league stop for many major league hopefuls. But there was one player on the team unlike the others, one whose motivations extended beyond the simple act of ascending to the sport’s highest peak. Jackie Robinson wasn’t just playing for himself, for his individual stat line or for his personal bank account. He was playing for Black people across the country, people who saw Robinson’s efforts as emblematic of what was possible in their own segregated corners of American society.

Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

But Robinson’s success was far from guaranteed in 1946. Two other Black players—pitchers Johnny Wright and Roy Partlow, both former Negro Leagues standouts—had played alongside Robinson that year, and both were demoted to the Class C Royals of Trois-Rivières, Quebec, during the season. For all the talk about whether Robinson was the most talented Black player in the Negro Leagues—and the general consensus that he wasn’t—his ability to perform under the racism and high scrutiny of that first year in white baseball seemed to confirm that he at least had the proper comportment. Indeed, Branch Rickey’s great experiment began at Montreal’s Delorimier Stadium, not Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, and Robinson passed with flying colors. En route to the Royals’ first Junior World Series championship in team history, Robinson led the league in batting average and fielding percentage. Robinson wouldn’t be called up to the Dodgers until April 10, five days before the start of the 1947 season, but already everything had changed.

On Opening Day of the ’47 Negro Leagues season, Newark set an attendance record of 12,552 fans. This was still more than two months before Larry Doby left to join Cleveland’s MLB team, becoming the first Black player in the American League, so the core of Manley’s championship roster was still there. But the early fan support was a false positive. As the season wore on, the enthusiasm for the Eagles wore off, and fans no longer cared as much about Doby or Monte Irvin or Max Manning. They wanted to see Robinson—the man who had become the Great Black Hope, the man who would prove Black worthiness with his bat and glove.

By fall, even after a strong follow-up season, Newark’s numbers were bleak. Opening Day’s record attendance aside, the Eagles managed only 57,100 ticket sales over the season, a 53% drop from 1946’s total of 120,293. And they weren’t alone in their misfortune. Up and down the Eastern seaboard, fans with the option of seeing Robinson and the Dodgers or one of the all-Black major league teams of the Negro National League were choosing the former. In ‘48, after another year of hemorrhaging, the Manleys decided to sell their team. With the New York Black Yankees and Homestead Grays also departing the NNL, the once-thriving organization was forced to fold, and its remaining few teams were absorbed by the Midwest’s Negro American League.

It was the worst-case scenario for Black baseball and a sure loss for the community at large—even as they celebrated the win of Robinson’s debut, even if the total fallout was yet unknown. Manley’s departing words, published on Sept. 21, 1948, in the New York Age conveyed as much. “Baseball is a rich man’s game,” she said. “Ruppert had his beer, Wrigley had his gum, Abe and I have only each other. I am not worried about myself, but I am concerned about the 400 men and their families who depend on the Negro Leagues.”

Before and immediately after Robinson’s MLB debut, 75 years ago today, there was scattered skepticism about the true impact of integration on Black baseball and those who earned their living from the industry. But in 1947, it was hard for many to see past the hopeful image of Robinson, clad in his crisp Dodger whites, blue No. 42 on his back. In 1947, there was no way to know that, three quarters of a century later, MLB’s integration efforts would remain largely symbolic, that even Robinson’s commitment to turning the other cheek and smiling through the pain couldn’t pry open the door to MLB front offices for more than a handful of token Black hires, land a single Black person in an owner’s box or ensure that Black players would represent more than 8% of the league.

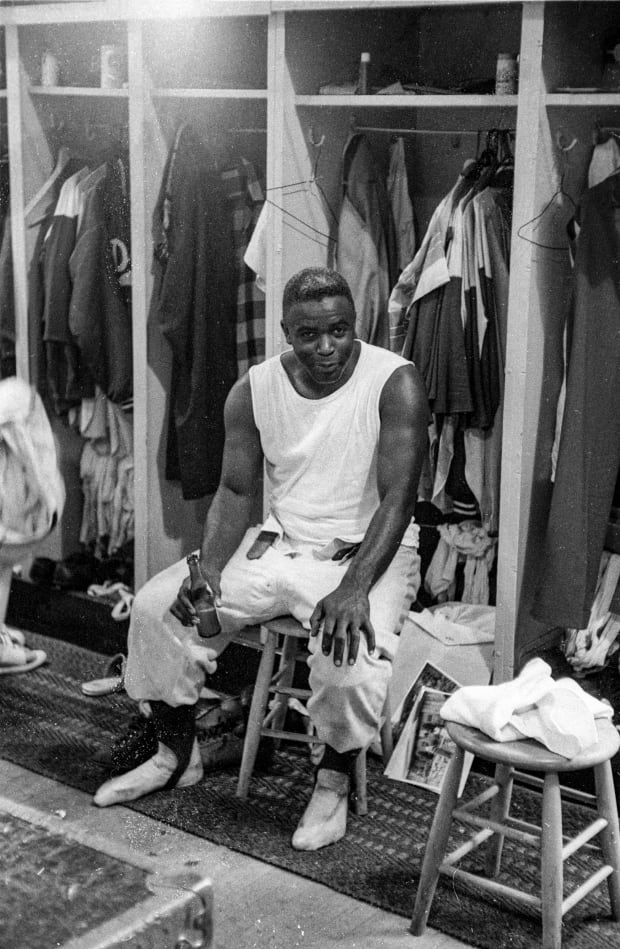

John G. Zimmerman/Sports Illustrated

The speedy collapse of the Negro National League was in direct contrast with the long and arduous road to integration. The push for Black inclusion began in the 1930s, inspired, in part, by the sporting successes of world heavyweight champion boxer Joe Louis and the Black members of the ’36 Olympic track and field team. Just as the Brown Bomber’s wins were seen as collective victories for all Black people, the medal-winning performances of Jesse Owens, Archie Williams, John Woodruff and others—including Jackie Robinson’s older brother Mack—were a pointed attack against racist attitudes both in Germany and at home. They also presented indisputable evidence that Black people could no longer be relegated to second place, in life or in sport. That was the hope, at least, because even as Black athletes began to make strides in the boxing ring and on the track, America’s pastime remained determined to bar them from its fields.

In 1939, Wendell Smith of The Pittsburgh Courier began publishing the results of his informal poll of MLB players, coaches and managers. How would they feel about playing with or against a Black player? Or managing one? The responses were varied but overwhelmingly positive, if not confusing. If players like Dizzy Dean and Honus Wagner supported the idea of Black players in Major League Baseball, and managers like the Dodgers’ Leo Durocher would be more than willing to coach a Black player “if the bosses said it was all right,” who was really responsible for continuing to darken MLB’s shameful color line?

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the former judge named MLB’s first commissioner, in 1920, took much of the blame. In 1938, Yankees outfielder Jake Powell mentioned during a pregame radio broadcast that he liked to stay in shape by “beating n------ over the head with my blackjack.” The station cut the audio immediately, but the damage was done. Protests ensued, forcing Landis to suspend Powell for 10 days. It wasn’t enough for some within the Black community who wanted him to receive a lifetime ban from the sport, or for the majority who still questioned why Black people weren’t allowed in the league at all. In 1942, when Landis finally made his first official statement on the matter of race in MLB, he effectively passed the buck to the owners, asserting that he worked for them and could in no way dictate their hiring decisions.

And such was the story for many years. As external pressure against MLB continued to mount, white executives continued to shake it; public appeals from members of the press—Black and white—were ignored, and private meetings weren’t worth the time they took to organize. In March 1942, Herman Hill, a Los Angeles–based correspondent for The Pittsburgh Courier, requested a tryout with the White Sox for Jackie Robinson and a Black pitcher named Nate Moreland. The Sox, who were at spring training in Robinson’s adopted hometown of Pasadena, Calif., promptly declined, with manager Jimmy Dykes saying it was “strictly up to the club owners and Judge Landis to get the ball a-rolling.” The next year, at MLB’s annual winter meetings, a contingent of Black reporters and newspaper publishers presented an even-handed case for integration. While the presentation was well received, it resulted in more inaction. Landis issued the reminder that “each club is entirely free to employ Negro players to any extent it pleases,” while the owners of said clubs failed to show any real interest.

Raymond Doswell, historian and vice president of curatorial services at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, wonders whether MLB’s constant deflection may have lulled Negro Leagues team owners into complacency, if the assumption that integration would always be a dream prevented Black baseball execs from adequately preparing for an inevitable reality.

“I think there was enough rumbling around the leagues, especially among the key teams, that [integration] could have been a possibility,” he said. “On the one hand, they should have been better prepared as business people.

“But at the same time, it’s 1945, and in spite of all the efforts of Blacks during the war, and the rumblings of integration and things like that, I think it fair to say that integration, as a whole, probably looked pretty bleak to a lot of observers living through it.”

Explore: Never-Before-Seen Photos of Jackie Robinson from 1956

Mark Kauffman/Sports Illustrated

Ultimately, it was a perfect storm of events that forced MLB’s hand and led to the blurring of its generations-old color line. There was World War II, which placed the United States firmly on the side of the “good guys”—and consequently displayed its glaring domestic hypocrisies. New York was the first state to enact legislation that attempted to atone for past racist sins. But by the time the Ives-Quinn Anti-Discrimination bill was signed into law March 12, 1945, thereby prohibiting race discrimination in hiring, Branch Rickey was already two years into a plan to integrate the Dodgers. His motivations were initially rooted in performance: The current roster was badly in need of a refresh, and while he had full intentions on revamping the team with younger, fresher players, he told the team’s board members that his plan “might include a Negro player or two.” Brooklyn’s brass, no doubt envious of the cross-town Yankees and itching for their own World Series title, agreed. That left Rickey to do what he did best, what he’d turned into an art while building the Cardinals dynasty in St. Louis a decade before: secure the best talent, and spend as little money as possible in the process.

Players jumping from team to team had always been an issue in Black baseball, and when Rickey signed Robinson without compensating—or even contacting—the Kansas City Monarchs’ ownership, co-owner Tom Baird had to admit that he didn’t actually have a signed contract with the infielder. They’d agreed to terms via telegrams and letters, a series of communication that Baird considered binding. It’s possible that a judge would have agreed, but the Monarchs owners didn’t dare take the Dodgers’ boss to court to find out.

Though the constant pleading and protest had yet to manifest anything tangible for pro-integrationists, they had become the dominant voice in the conversation. Even Black reporter Joe Bostic pivoted from his 1942 assertion that “entry of even ONE Negro player on [an MLB] team would serve completely to monopolize the attention of the Negro and white present followers of Negro baseball…” and his 1943 suggestion that integrating with “an entire Negro-owned, controlled, and personneled team” would be the ideal way to keep money and jobs in the Black community. By April ’45, Bostic and Jimmy Smith, a sportswriter for The Pittsburgh Courier’s Harlem bureau, had adopted the approach of others in the industry who believed that the best way to expedite integration was to showcase top individual talent. Nothing came of it, but their arranged tryout for Negro Leagues pitcher Terris McDuffie and outfielder Dave “Showboat” Thomas at the Dodgers’ spring training camp was but another crack in MLB’s all-white veneer.

So that fall, once the wheels of integration were clearly in motion, questioning how it happened would have been deemed akin to not wanting it to happen at all. Doswell notes that “almost immediately after Robinson signed, teams locked up their players in paperwork,” but there still wasn’t a single Black team owner willing to decry the overall integration effort, not after so many years of stops and starts and so much heartbreak. Already, the Negro Leagues owners had been accused of caring more about their personal profits than the progress of their people. They’d also watched as Satchel Paige faced the ire of the Black community when he publicly wondered about the travel accommodations for Black players on white teams and suggested that any MLB offer he received would need to match the considerable salary he was making on his side of the color line.

For owners of Negro Leagues teams, the post-Robinson survival strategy seemed to be “watch and wait,” and, the longer they waited, the more frustrated they became with what they saw. Rickey grabbed one Black player after another, all the while castigating Black baseball in the press. Despite failing to sign a Black American player to his team, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith publicly condemned Rickey’s refusal to fairly negotiate with Black team owners. Griffith profited handsomely from the rental of Griffith Stadium to Negro Leagues teams; his motivation for commenting was thus financial, not moral. Rickey, meanwhile, made his opinion of Black baseball leagues clear: “Clark Griffith, to the contrary, I have not signed a player from what I regard as an organized league.”

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Rickey’s continual assertion that the Negro Leagues were illegitimate and “in the nature of a racket” didn’t just bruise the egos of the men and women who’d defied incredible odds and exhibited extreme resourcefulness and creativity to build successful teams and leagues. It also justified their exclusion from MLB, even as some of the players they’d discovered and developed were considered worthy of inclusion—then and in the future.

In the most disturbing of coincidences, it was another Dodgers exec, general manager Al Campanis, who further emphasized the supposed inability of Black people to lead baseball clubs. “I truly believe that [Black people] may not have some of the necessities to be, let’s say, a field manager, or perhaps a general manager,” Campanis told Ted Koppel in April 1987, just ahead of the 40th anniversary of Robinson’s Dodgers debut. “How many quarterbacks do you have; how many pitchers do you have that are Black? The same thing applies.”

Koppel’s question—“Why is it there are no Black managers, no Black general managers, no Black owners?”—was delivered 15 years after Robinson himself expressed disappointment that his beloved sport had yet to fully welcome his beloved people. “I am extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon,” he said before Game 2 of the 1972 World Series, in what would be his last public appearance, “but must admit that I am going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third-base coaching line one day and see a Black face managing in baseball.”

There had, of course, been Black managers, general managers and owners in the Negro Leagues, but at no point during the integration debate did anyone suggest that the process include individual owners or front office employees. MLB did make an early exception to its all-white leadership rule, however, when Alex Pompez, the Cuban owner of the Negro National League’s New York Cubans and a convicted racketeer with ties to mobster Dutch Schultz, was hired by the New York Giants to oversee scouting and operations in Latin America. Numerous Negro Leagues owners, including Abe Manley, had used cash made through illegal lotteries to finance their teams, but in the case of Pompez, a sketchy past mattered less than an ability to source cheap talent.

MLB teams continued to scour the remaining Black clubs for players (Henry Aaron left the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League to sign with the Boston Braves in 1952), but those players were Black Americans, and the managers and executives who’d cultivated them were largely ignored. As a result, they were unable to serve as necessary safeguards between Black players and the often unwelcoming world of white baseball. Wright and Partlow, Robinson’s minor league teammates, knew this all too well. Unlike with Robinson, who could take the sneers and jeers in stride while setting records and logging wins, the bright lights of integration’s stage were too much for Wright and Partlow to bear—especially while playing for Royals manager Clay Hopper, who was staunchly opposed to integration. Wright and Partlow both struggled on the mound, and, after finishing the ’46 season in Quebec, they returned to the Negro Leagues in ’47.

But the option to return to Black baseball soon disappeared, and the Black players who didn’t get the call to go to the majors, or who were unwilling and/or unable to navigate the persistent hostilities in MLB (it took until 1959 for every team to sign at least one Black player and many more years after that for the league to do away with its unspoken quota that limited Black players to a handful on any given roster), saw their careers torpedoed with the demise of the Negro Leagues. Even now, with the number of Black MLB players as low as it was in the ’50s, it’s not hard to trace the line back to those days, when the color line was never erased but simply redrawn, making space for a few athletes willing to look past the league’s ugliness, while leaving the vast majority—managers, executives, owners, and some players, too—on the outside.

Richard Meek/Sports Illustrated

When Robinson addressed the crowd at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium on October 15, 1972, he was 53 and in failing health; he’d grown and matured and had the benefit of hindsight tucked tightly in his heart. Any wishful thinking Robinson may once have harbored, any hope of Black inclusion and equity to be catalyzed by his harrowing sacrifices had long dissipated. In his autobiography, I Never Had It Made, published less than two weeks after that game and just four days after Robinson’s death, he acknowledged that, back in ’47, he had simply been a small actor in a larger drama, one that valued green dollars more than Black equity. “As I write this twenty years later,’’ he wrote, “I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, in 1919 at my birth, I know that I never had it made.’’

This—as much as his Junior World Series Championship with Montreal, his Rookie of the Year win with the Dodgers or his stolen base title that first year in the Majors—is Jackie Robinson’s legacy. It is the unceremonious death of the Negro Leagues and the failure of MLB to truly open its arms to all the Black participants in the sport who loved baseball and had nowhere else to turn. It is the harsh reality that today, 50 years after Robinson’s autobiography was published and 75 years to the day after he first took the field at Ebbets, as Major League Baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson Day, with players wearing his No. 42 and the league offering its obligatory thanks to his courage, Black people in that very baseball league still don’t have it made.