A 23-year western drought has drastically shrunk the Colorado River, which provides water for drinking and irrigation for Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California and two states in Mexico. Under a 1922 compact, these jurisdictions receive fixed allocations of water from the river – but now there’s not enough water to provide them.

As states try to negotiate ways to share the decreasing flow, the U.S. Department of the Interior is considering cuts of up to 25% in allotments for California, Nevada and Arizona. The federal government can regulate these states’ water shares because they come mainly from Lake Mead, the largest U.S. reservoir, which was created when the Hoover Dam was built on the Colorado River near Las Vegas.

These five articles from The Conversation’s archive explain what’s happening and what’s at stake in the Colorado River basin’s drought crisis.

1. A faulty river compact

The idea of negotiating a legally binding agreement to share river water among states was innovative in the 1920s. But the Colorado River Compact made some critical assumptions that have proved to be fatal flaws.

The lawyers who wrote the compact knew that the Colorado’s flow could vary and that they didn’t have enough data for long-term planning. But they still allocated fixed quantities of water to each participating state. “We know now that they used optimistic flow numbers measured during a particularly wet period,” wrote Patricia J. Rettig, head archivist of Colorado State University’s Water Resources Archive.

Nor did the compact encourage conservation as the West’s population grew. “When settlers developed the West, their prevailing attitude was that water reaching the sea was wasted, so people aimed to use it all,” Rettig observed.

Read more: Western river compacts were innovative in the 1920s but couldn't foresee today's water challenges

2. Temporary cuts aren’t big enough

Western states have known for years that they were taking more water from the Colorado than nature was putting in. But reducing water use is politically charged, since it means imposing limits on such powerful constituencies as farmers and developers.

In 2019, officials from the U.S. government and the seven Colorado Basin states signed a seven-year drought contingency plan that temporarily reduced states’ water allocations. But the plan did not propose long-term strategies for addressing climate change or overuse of water in the region.

“Since 2000, Colorado River flows have been 16% below the 20th-century average,” wrote water policy experts Brad Udall, Douglas Kenney and John Fleck. “Temperatures across the Colorado River Basin are now over 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 degrees Celsius) warmer than the 20th-century average, and are certain to continue rising. Scientists have begun using the term ‘aridification’ to describe the hotter, drier climate in the basin, rather than ‘drought,’ which implies a temporary condition.”

Read more: Western states buy time with a 7-year Colorado River drought plan, but face a hotter, drier future

3. The looming threat of dead pool

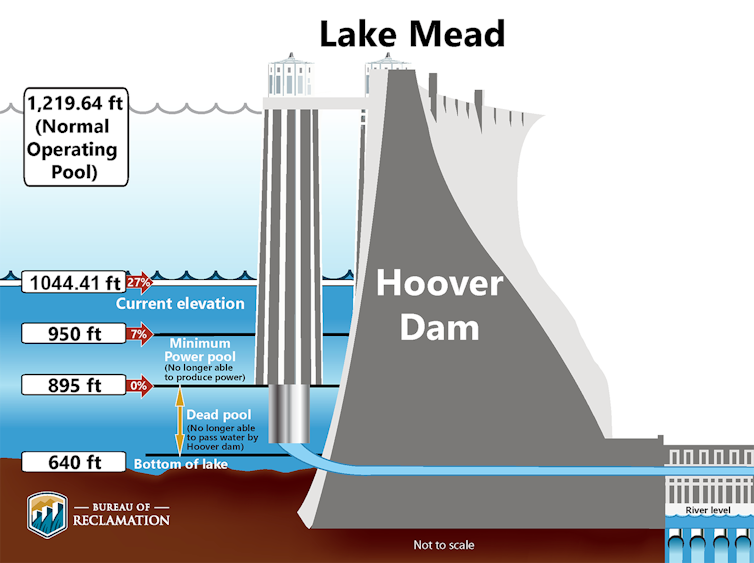

Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the other major reservoir on the lower Colorado River, were created to provide water for irrigation and to generate hydropower, which is produced by the force of water flowing through large turbines in the lakes’ dams. If water in either lake drops below the intakes for the turbines, the lake will fall below “minimum power pool” and stop producing electricity.

If water in the lakes dropped even further, they could reach “dead pool,” the point at which water is too low to flow through the dam. This is an extreme scenario, but it can’t be ruled out, University of Arizona water expert Robert Glennon warned. In addition to drought and climate change, he noted, both lakes lie in canyons that “are V-shaped, like martini glasses – wide at the rim and narrow at the bottom. As levels in the lakes decline, each foot of elevation holds less water.”

Read more: What is dead pool? A water expert explains

4. Why hydropower matters

Climate change and drought are stressing hydropower generation throughout the U.S. West by reducing snowpack and precipitation and drying up rivers. This could create serious stress for regional electric grid operators, according to Penn State civil engineers Caitlin Grady and Lauren Dennis.

“Because it can quickly be turned on and off, hydroelectric power can help control minute-to-minute supply and demand changes,” they wrote. “It can also help power grids quickly bounce back when blackouts occur. Hydropower makes up about 40% of U.S. electric grid facilities that can be started without an additional power supply during a blackout, in part because the fuel needed to generate power is simply the water held in the reservoir behind the turbine.”

While most hydropower dams are likely here to stay, in Grady’s and Dennis’ view, “climate change will change how these plants are used and managed.”

5. The resurrection of Glen Canyon

Lake Powell was created by flooding Glen Canyon, a spectacular swath of canyons on the Utah-Arizona border. As the lake’s water level drops, many side canyons have reemerged. Effectively, climate change is draining the lake.

This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to recover a unique landscape, wrote University of Utah political scientist Dan McCool. “But managing this emergent landscape also presents serious political and environmental challenges.”

In McCool’s view, a key priority should be to give Native American tribes a meaningful role in managing those lands – including cultural sites and artifacts that were flooded when the river was dammed. The river has also deposited massive quantities of sediments in the canyon behind the dam, some of which are contaminated. And as visitors flock to newly accessible side canyons, the area will need staff to manage visitors and protect fragile resources.

“Other landscapes are likely to emerge across the West as climate change reshapes the region and numerous reservoirs decline. With proper planning, Glen Canyon can provide a lesson in how to manage them,” McCool observed.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.