It will take a massive shift in the way government and its agencies work with all New Zealanders to achieve the laudable goals of this week's emissions plan and Budget funding, writes Rod Oram

Budget 2022 and the Emissions Reduction Plan suffer from the same problem. They are written well. But they are read badly.

The writers offer compelling goals for us as a nation, and logical architecture for how we could achieve them.

But too many readers, at least in their public pronouncements, fail to offer well-evidenced views on whether these are the right ambitions and actions. They rush straight into criticising specifics, and to declaring their choices of sins and omissions.

Constructive criticism is vital to spur us to do better. But if we don’t take the first step, we’ll never agree on our goals. Then we won’t work together effectively. So, we won’t achieve much.

No doubt a lot of people are put off by the complexity and detail of the Budget and the Plan. But both are highly accessible thanks to their layering of information from brief summaries to long expositions and abundant detail.

The ERP is the primary document. It proposes goals and pathways which, if we execute them well, will make Aotearoa more sustainable in many aspects of our environment, economy, society and culture over coming years and decades.

Thanks in no small measure to the deeply researched recommendations by the Climate Change Commission to the Government, it is one of the most succinct, logical and integrated expressions any country has produced to date on its climate challenges and opportunities, albeit expressed only in broad terms.

That’s my verdict after years of reading such documents from around the world. Acknowledging, of course, the task is easier for us than for bigger and more complex entities such as the UK or European Union.

While the Budget is also strategic about those goals, it essentially describes only how the Government will collect money and spend it on them. In this Budget Finance Minister Grant Robertson has struck the right balance between spending to keep our current economy and society running, while investing more than ever before in the future of both.

But that latter spend will have to ramp up enormously, once we have detailed climate-driven transformation plans across government, business and society at large. This is the link for the Budget overall and this is the link for the spending on climate-related measures.

But the Budget tells us little about how we’re going to do it. The Plan offers more on that. But there’s still lots for us to work out together. To do that, we have to make a massive shift in culture and practice in the way government and society work together – more on that later.

This is a task for all of us. Everyone has hopes, fears and ambitions on climate; and each of us can play our tiny part in helping collectively to rise to Aotearoa’s climate challenges and opportunities.

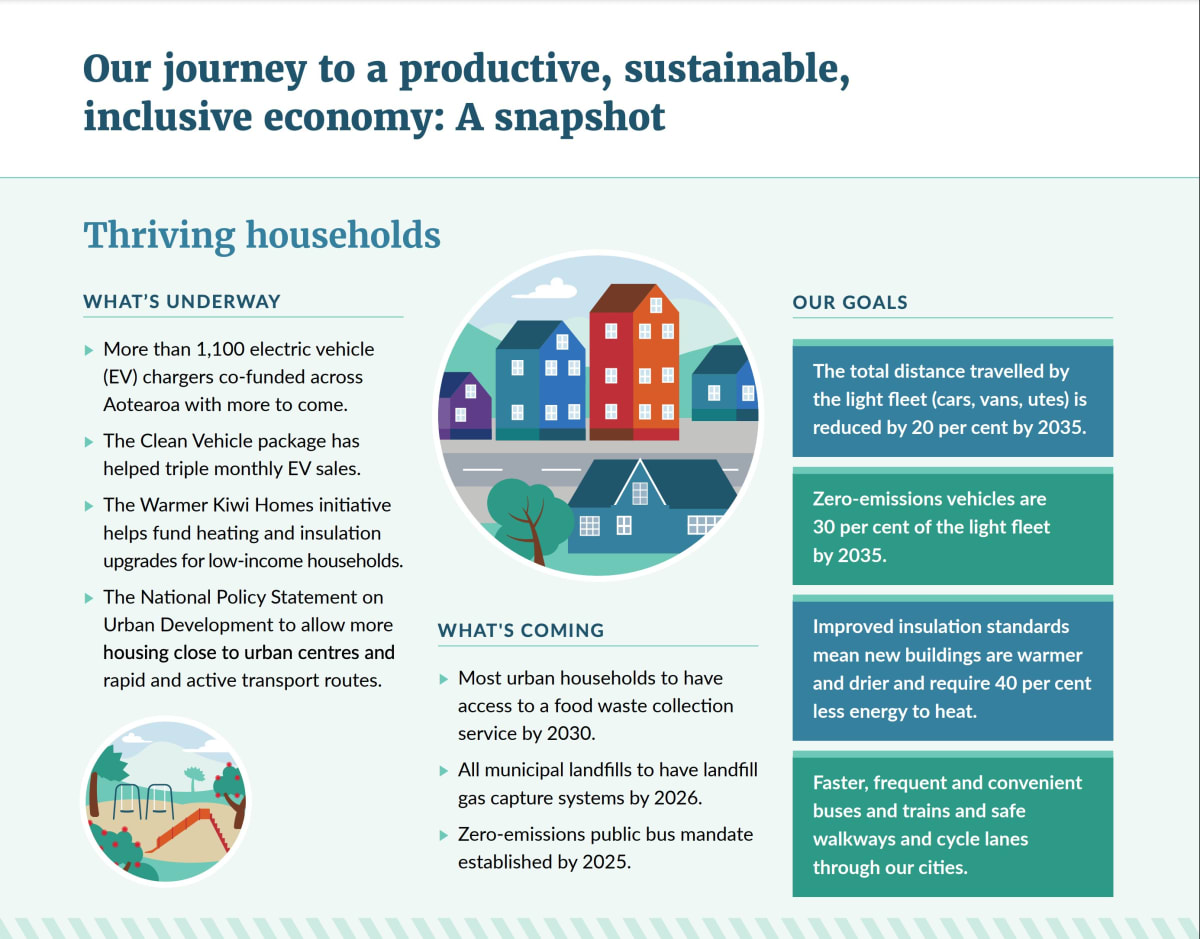

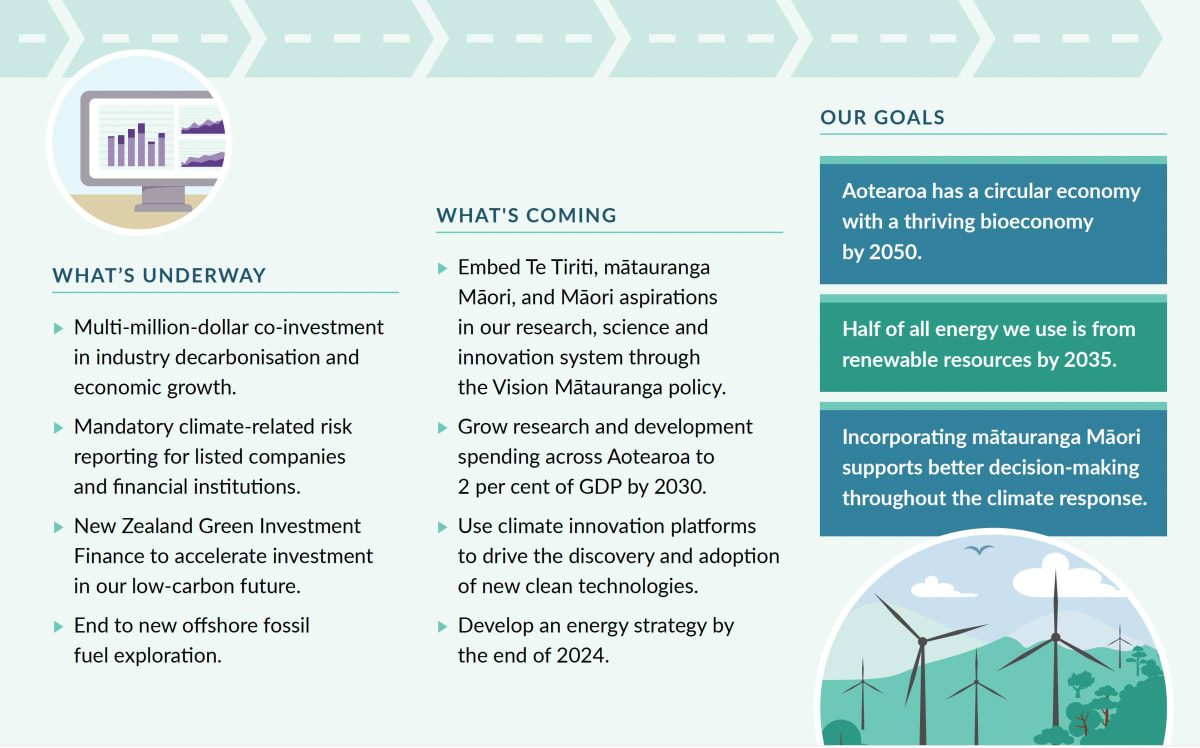

To start, you don’t even need to read the 12-page summary of the Plan. The graphics on pages 10 and 11 give you a good idea of where we’re heading. In each reproduced below, are just some of the main themes and goals. I hope you find something in them you want to live, benefit from, and spread the word about. That's how real climate action happens - with each of us taking responsibility for what we want and can do, however small or large our contribution might be.

The first graphic covers our built-environment. The themes range from the deeply systemic – how we design and improve our towns and cities in ways that reduce their emissions – to the highly specific – how we upgrade our homes so they are warmer and healthier and more energy efficient. Achieving the four goals highlighted (there are more in the full Plan) would make our lives much more pleasant at home, and around our communities, and help us tackle the climate crisis.

The second graphic covers our natural environment. Nature-based solutions is the most important goal here. These help us restore ecosystems so we reduce the causes of the climate crisis (by, for example, sequestering atmospheric carbon in trees). In turn the healthier ecosystems offer us more protection from and adaptation to the effects of the climate crisis such as flooding.

Globally, nature-based solutions will likely contribute one-third of emission reductions, scientists estimate. This pathway is perfect for us, since we have the largest stock of natural capital per capita in the world (bar oil and gas nations), the World Bank estimates.

The third graphic covers high value exports and innovation. While effective climate responses by many of our sectors will drive both elements of economic prosperity, the graphic focuses only on agriculture. After all, the sector is responsible for half our emissions and half our exports. The graphic offers only a few of farmers’ many key climate risks, responsibilities and opportunities, subjects I’ve written extensively on, for example, here. But it captures the nub of the issues. Responding positively to these is the best business opportunity our farmers are ever going to have.

The fourth graphic gives us three of the biggest, overarching goals; four policies underway; and four big themes for further work. All are vital in their own way. They capture some of the crucial elements in our response to the climate, and the great benefits we will harvest from acting vigorously and effectively.

Best of all they point to two huge advantages we have compared to most other countries: our abundant natural capital and our indigenous knowledge. Together, they will make us a more sustainable, equitable and prosperous society.

For a fuller picture, read the 12-page summary of the Plan. Or even, better the full Plan, or at least its 23 case studies of encouraging climate action underway across the economy and society. Searching on the words 'case study' will flick you from example to example through the 348-page document. Or search for your favourite topic or sector. This link takes you to both documents and an online summary.

But the single most worrying paragraph in the whole document is this one on page 24:

“This is an all-of-government plan involving many agencies, departments and ministries, and their ministers. Making it work requires new ways of coordinating effort across government, as well as between government and Māori, local government, the business community and civil society.”

Brave words. But the government - politicians and civil servants - are failing to live up to them. While they picked up many recommendations from business and civil society organisations, they still treated it as a government document-in-the-making.

‘It’s your role to advise us. It’s our role to make policy’ was the essential attitude. Far too often, people in government were too secretive, too untrusting, too hard to engage with, a number of people and organisations who worked with them have told me. They worry these attitudes are persisting as work to flesh out the Plan progresses.

We the public crowd sourced the ideas for the Plan - with more than 10,000 submissions on the draft Plan alone. It's our Plan. So, come on, government, help us help you crowd source our actions.

We must work together. These are intensely interdependent climate / economic / social / environmental / cultural issues. They are so complex, the time to solve them so short and the resources so scant, we must simultaneously design and act in collaborative, trusting, and iterative ways.

There was no word on that in the Plan. But don’t blame this Government or generation of civil servants. It’s deep in our political culture. It was even worse from the late-1980s to the early-1990s when a tiny group of politicians, civil servants and business leaders rammed through economic reforms. The fundamental changes were urgently needed. But some dysfunctional processes and damaging decisions forced heavy collateral costs on people and the economy. Ultimately, they denied us some of the gains we would have otherwise made from reforms.

We are now at an even more critical juncture in our history. There is just enough time left for the government (politicians and civil servants) to radically change their culture so they work collaboratively with the rest of society. Then together we can grow this skeletal Plan into a powerful driver of transformation.

Two other crucial players have to change their cultures too if they want to play constructive roles.

National, in all its utterings on climate over the years, has clearly shown it has no idea of how effective climate action works abroad in politics or business. For example, Chris Luxon, National’s leader, branded as corporate welfare the Plan’s public investment to help some companies take big technology leaps to reduce their emissions and increase their competitiveness. He said they can well afford to make those investments themselves.

He would have known as a recent chief executive of Air New Zealand and a former executive of Unilever (one of the world’s corporate leaders on climate) that was utterly untrue. Business-as-usual absolutely won’t deliver transformations such as Sustainable Aviation Fuel. Yet he still indulged in that cheap, facile political lie. If Luxon wants to know what all-stakeholder action on a gnarly climate issues looks like, he should spend 5 minutes looking at the UK Jet Zero Council website. Every participant in the supply chain from fuel companies to airlines, and the relevant minister plus airports and others in between, is represented. Together they are working on building fast a string of SAF plants in the UK at around US$1 billion a piece.

The other player is Fonterra, which with its farmer-shareholder-suppliers is completely responsible for some 20 percent of our entire economy’s emissions. Its complete silence on the Plan spoke volumes. It wouldn’t even be bothered to say ‘thank you’ for $710 million from taxpayers over the next four years for a new Centre for Climate Action on Agricultural Emissions.

That was no surprise since Fonterra has zero credibility on climate. It still refuses, for example, to set goals for reducing its own emissions of methane, one of the most potent of greenhouse gases. If it doesn't cut them New Zealand will fail to meet its international climate commitments. That would do untold damage to our reputation and economy. And to the business of Fonterra and its farmers too.

Likewise the few lukewarm responses from elsewhere in the farming sector showed they still believe they are the best in the world, and they have loads of time yet to gradually clean up their act.

Clearly, they are unaware of many examples of climate leadership around the world by farmers, food companies, such as Nestlé, Fonterra’s largest customer, and new food tech companies such as Mosa Meat in the Netherlands.

So, a Plan, a Budget…and massive, urgent work for us all.