The story so far: A key reason India fell short of achieving its ambitious plan to install 175 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy from solar, wind, biomass and hydro resources by the year 2022 was the sluggish pace of its rooftop solar power installation programme, which generated a mere 5.87 GW against a target of 40 GW by the end of the year.

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy later underlined the “tardy pace of progress” of the programme in a report and asked the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) to ensure wider adoption of grid-connected rooftop solar photovoltaic projects (RSPV) to achieve the target before the revised deadline of March 2026.

Over the past decade, the government has undertaken a series of measures and pushed through policies to make rooftop systems more accessible and affordable, but the target remains far from achieved. In a fresh attempt to spur activity in the segment and improve the share of solar power in the grid, the Centre last month unveiled the Pradhan Mantri Suryodaya Yojana (PMSY) to tap into the vast potential of rooftop projects in residential areas. The scheme found a special mention in the interim Budget 2024, with Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman reiterating PM’s commitment that the scheme would help one crore families get up to 300 units of free electricity per month with savings of up to Rs 18,000 annually.

Also Read | A sunshine initiative: On the government’s rooftop solar panel plan

What is a rooftop solar system and how does it work?

Vacant spaces on the ground, and rooftops of houses and commercial and industrial (C&I) buildings receive abundant raw solar energy which can be harnessed to produce solar power. When solar photovoltaic panels that convert sunlight into electricity are placed on the top of such buildings, it is known as a rooftop solar system. A RSPV system can be either grid-connected or a standalone unit known as an off-grid solar system.

As the name suggests, an off-grid solar system is not connected to any wider electric supply system. Instead, it uses storage devices like batteries that are expensive and bulky. While such a system is self-sustaining, it only stores electricity produced in the unit.

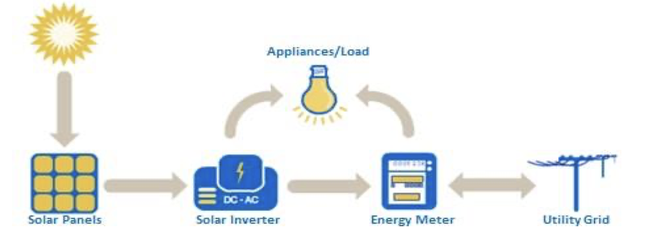

A grid-connected rooftop solar system, meanwhile, feeds solar energy into the utility grid. Typically, such a system includes solar PV modules, an inverter, a module mounting structure, monitoring and safety equipment and meters. An inverter converts the DC power generated from solar panels to AC power, which is then fed to the grid, while meters keep track of the electricity injected and drawn from the utility grid.

In a grid-connected rooftop solar system, if the plant produces more solar energy than the installer uses, the surplus is exported to the grid. On cloudy days when solar energy is unavailable, power is drawn from the grid. A bi-directional or net meter installed on the premises of a consumer records the energy flow in both directions and the net energy used is calculated at the end of the billing period. A consumer has to pay for the net energy units used, which is the difference between total imported units and exported solar units. This is called net-metering.

A grid-connected solar power system reduces the consumption of electricity provided by corporate or state power suppliers and helps a consumer save on electricity costs.

In the case of gross metering, while the homeowner has to pay for the power drawn from the grid at rates applicable to consumers in the category, the State power distribution company (discom) pays the rooftop solar PV homeowner for the power injected into the grid as per the power purchase agreement.

Presently, there are two models for the installation of a rooftop solar system. In the CAPEX model, a consumer bears the cost and owns the system. In the RESCO model, the system is owned and maintained by a third-party developer from whom a consumer can purchase the generated energy by paying a pre-decided tariff every month.

What is driving India’s solar power plan?

India gets around 250 to 300 days of sunshine per year; equivalent to about 2,200–3,000 sunshine hours in a year depending upon the location. In terms of energy, it receives around 5,000 trillion kWh of solar energy every year, and the incidence ranges from 4 to 7 kWh per square metre per day in most areas. Since this translates to immense potential, the government has undertaken a series of policy measures and provided financial incentives, keeping solar energy at the forefront of the push to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2070 and meet 50% of its electricity requirements from renewable sources.

India, one of the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, has set a target of 500 GW from non-fossil sources by 2030. For this, the country aims to install 485 GW of renewable energy capacity. Solar energy has emerged as a major prong of India’s commitment to achieve these ambitious targets.

In 2010, the Centre launched the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM) to focus on the promotion and development of solar power. The country had less than 20 MW of solar energy capacity at the time. After the Narendra Modi-led government took over in 2014, it set a target of 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022 and revised the earlier goal of the mission of 20 GW of solar power to 100 GW, with no change in the timeline. Apart from solar power, the goal was to install 60 GW from wind, 10 GW from bio-power and 5 GW from small hydro-power. The government launched a grid-connected rooftop solar programme in December 2015 with incentives and subsidies for the residential and institutional sectors. The second phase of the project was launched in February 2019 to achieve 40 GW capacity from rooftop projects by 2022. The remaining 60 GW was to come from utility-scale or large-scale power plants (solar parks). The Centre included the provision of a subsidy of up to 40% for solar installations in the residential segment.

Between 2011 and 2021, the sector grew at a compound annual growth rate of around 59% from 0.5GW to 55GW, as per a report of JMK Research and Analytics and the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). Tariffs fell from Rs 9.28/kWh in 2011 to Rs 2.14/kWh in 2021, while annual capacity addition grew from 0.2 GW in 2011 to 11 GW in 2021 during the same period.

Consequently, the government increased the installed solar energy capacity target to 300 GW by 2030. The Ministry also introduced an e-marketplace for consumers, vendors and representatives of banks providing loans to simplify the procedure for installing rooftop solar plants for residential consumers. By the end of 2022, India had installed a total renewable energy capacity of 120.90 GW. Solar power capacity hit 62 GW and India emerged as a global leader in solar energy capacity, ranking 4th in the world.

The rooftop sector, however, recorded underwhelming growth, achieving just 7.5W of the 40 GW target. This time, the Centre changed the timeline, giving a four-year extension to the rooftop programme till March 2026, without any financial implication or change in the total target capacity.

Despite government nudges, solar power installed capacity had reached only 73.31 GW, with rooftop solar around 11.08 GW by December 2023. Commercial and industrial (C&I) consumers led rooftop solar growth with approximately 80% share in the rooftop solar market.

In its report, the IEEFA attributed the tepid growth of rooftop solar to limited consumer awareness, inconsistent policies, high capital cost and a dearth of suitable financing options. “Policy uncertainty and regulatory pushbacks have been a major factor limiting growth in rooftop solar… More importantly, restrictions and/or ambiguity on provisions such as banking of electricity and net metering have undermined rooftop solar opportunities in India,” the report added.

The scheme relied upon discoms for installations, but with large subsidies available on supplied electricity as well as low consumption of power in the majority of Indian households, the segment failed to take off as planned. De-centralised electricity from RTS systems also took away consumers from discoms who have high monthly consumption.

“Cost savings are the main driver for consumers to adopt solar. However, with lowering of net metering and limiting of banking provisions, the opportunity for cost savings is significantly reduced, especially for large and medium industrial consumers,” the IEEFA report adds.

The continued underperformance of the rooftop solar segment has thus exposed the gap between potential and performance with wide implications for India’s sustainability plans, especially against the backdrop of an ever-growing power demand.

Where does the rooftop solar programme fit in India’s green ambitions?

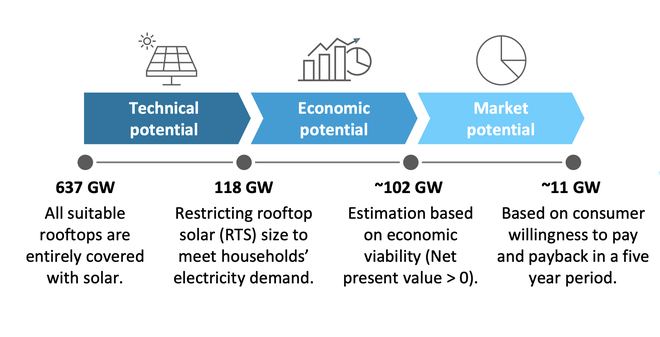

As per the latest estimates, India has installed around 2.7 GW capacity in the rooftop residential sector in 6.7 lakh households. An assessment by the Delhi-based think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) in November found that over 25 crore households in the country have the potential to deploy 637 GW of solar energy capacity on rooftops. Deploying one-third of this total solar potential could support the entire electricity demand of the residential sector in India. This could prove crucial as India is expected to have the largest energy demand growth in the world over the next 30 years.

However, the technical potential (the amount of solar power that can be feasibly installed) is much less. Most residential consumers across States fall into low-consumption slabs, especially in rural areas, making solar energy unaffordable without financial support.

Around 85% of the technical potential is concentrated in rooftop solar systems sized between 0-3 kW. Around 30% of the technical potential lies in the 0-1 kW category, but the category is not recognised in policy and subsidy schemes. According to the estimates provided by the Ministry, the cost of installing a 1-2 kW solar power system is approximately ₹45,000 per unit and units up to 3kW are eligible for a subsidy of about ₹14,000 per unit. The life expectancy of solar panels is around 25 years, and the payback period ranges from 3.5 to 4.5 years, provided there is proper maintenance.

Hence, consumers using as low as 1 kW require greater incentives to adopt rooftop solar. “The MNRE subsidy is effective for an RTS system size of 1-3 kW, and can increase the economic potential by nearly 5 GW by making systems economically feasible for more consumers with no change in system sizes above 3 kW,” the CEEW study concluded.

The Council further suggested targeted capital subsidies, particularly for RTS systems of size 0-3 kW and introducing low-cost financing options with a fast approval process and a separate line of credit for residential consumers.

The micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) sector, which accounts for roughly 30% of industrial energy consumption in the country, is another untapped sector. Estimates show that the 63 million MSMEs offer solar rooftop potential of 15-18 GW, which is more than 30% of the overall rooftop target of 40GW.

Promit Mookherjee, an Associate Fellow at the Centre for Economy and Growth, says a shift to rooftop solar could help the sector tide over frequent power cuts and reduce production costs by lowering expenditure on grid electricity, with the share of electricity cost in total operational cost higher for MSMEs compared to larger firms. MSMEs in the manufacturing sector mostly operate during the day, which means that rooftop solar would cater to their power demand without any significant change in operational patterns or investment in battery storage systems, he adds. Financing, however, remains a challenge for the sector. Many of these firms are not part of the formal economy and tend to have poor creditworthiness, he points out, suggesting a cluster-based approach to overcome technical and financial hurdles.

What is the new rooftop policy?

As part of the Pradhan Mantri Suryoday Yojana, the Centre will bear the entire cost of setting up rooftop solar systems for households that consume less than 300 units of electricity per month. The subsidy in the segment will increase to 60% from 40% and the remaining will be financed by a private developer affiliated to public sector units of the Power Ministry.

R.K Singh, Minister for Power and New and Renewable Energy, said that 60% of the cost of installation will be subsidised by the Centre and for the rest, the PSU will avail of a bank loan and repay from the cost of electricity used by the household over and above the 300 units. Since the customer will still be required to fund 40%, the scheme will pay itself back in 7-10 years, after which the consumer can sell electricity back to the grid and earn, he added.

This means that the scheme puts the onus of providing electricity to households on central government companies instead of individual power distribution companies. The change is likely to have a positive impact on the rooftop solar sector as distribution companies, most of which have been struggling with financial problems, haven’t shown much enthusiasm. So far, these distribution companies have been hesitant to switch high-consumption customers to rooftop solar schemes as it means a significant loss of revenue.