Pereant qui ante nos nostra dixerunt: may those who utter our words before us perish. This lighthearted Latin curse speaks a truth many readers and writers have felt: to have our thoughts articulated by someone else.

Coenraad de Buys is unruffled by such a possibility. He is the antihero of Willem Anker’s award winning 2014 Afrikaans novel, Buys. Vagabond philosopher that he is, Buys reflects on the nature of memories. Their substance is flaky; their origin sometimes obscure. You might glimpse them in a glass darkly or even find them outside your own mind – in the books you read. When this happens to Buys, he feels

as if the stories of others capture something of my own life … the outlines of a conversation, a fly on the edge of my hat, but not the words.

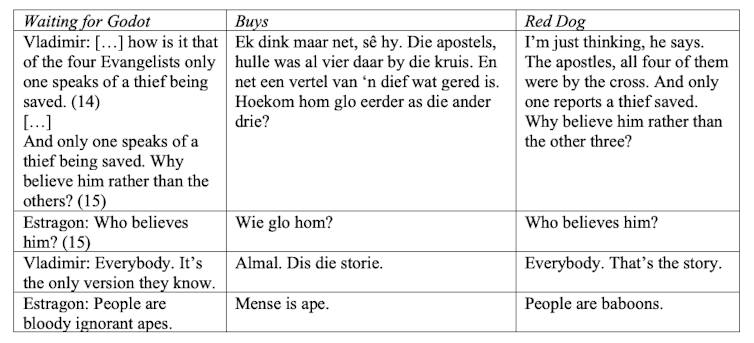

This musing occurs during one of the novel’s rare moments of uneventfulness. Nothing happens; no one comes or goes. Maybe that’s why the text opens onto four pages of near-undiluted dialogue from celebrated Irish author Samuel Beckett’s 1952 play Waiting for Godot. Of course, it’s one thing for a character to be cavalier about the words of others, and quite another for an author.

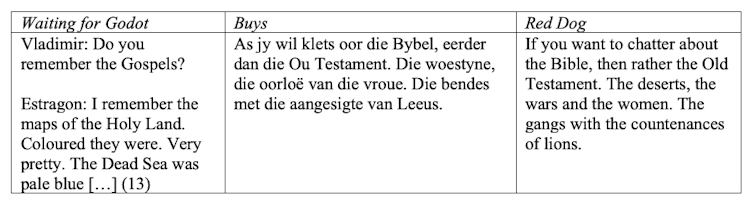

According to my analysis, at least 78 lines from Beckett’s play are reproduced in Buys without significant alteration – a fact which, if noticed, has not been noted to my knowledge.

The Afrikaans text carries no acknowledgement of Waiting for Godot, nor does it acknowledge Beckett’s influence. The English translation, Red Dog (2019), also doesn’t credit the play, though Beckett is mentioned with US writer Cormac McCarthy as an author whose “remains” might be recognised.

The McCarthy affair

Not long after the English text appeared, a reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement and The Guardian noted close correspondences with McCarthy’s epic novel Blood Meridian.

The reviewer took issue with Red Dog’s “clunky act of mimicry” and questioned whether McCarthy was sufficiently acknowledged. He writes that Anker walks a fine line between appropriation and plagiarism.

This drew a defence from the book’s translator, Michiel Heyns. Anker himself explained that these correspondences belong to the book’s “playful rewritings and quotes (which), when noticed, would enrich … broader conversations”.

Enter Beckett

I said earlier that Buys opens onto Waiting for Godot. A more precise formulation: it yields the floor, gives itself over to Beckett without giving him any of the credit.

For scale and seriousness, consider that the amount of appropriated material exceeds the nearly 60 uncredited ‘borrowings’ recently identified in Australian author John Hughes’s prize-withdrawn novel, The Dogs. It also exceeds what Faber and Faber, Beckett’s publisher, considers “fair use”.

Putting aside the question of copyright, the sustained nature of the reproduction of Godot perhaps offers its own curious form of mitigation. Surely Anker wants us to pick up on this wholesale transfer? And isn’t it a truth universally acknowledged that a writer in possession of an individual talent might sometimes be in want of a riff?

In defence of Anker?

That was more or less US-born poet T.S. Eliot’s position, himself no stranger to charges of unscrupulous liftings. But Eliot gets off by having practised what he preached:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn.

Now, one could mount an unorthodox defence and claim that Anker is a bad writer. You could argue that he has simply failed to pressure-cook his source into something rich and strange. Embarrassing, true, but the plea would at least reduce the charges from ethical to aesthetic badness.

Trouble is, Anker isn’t a bad writer – quite the opposite. This is borne out by the awards Buys has won: among them the UJ Prize (2015), Hertzog Prize (2016), K. Sello Duiker Memorial Award (2016) and, of course, Red Dog’s longlist nomination for the Man-Booker International in 2020.

Add to this the voice of Anker’s translator, Heyns, who cites the author’s “incredible linguistic dexterity” as a charm against temptations to literary theft:

Anker is more than capable of writing his own novel.

It may then be asked: why doesn’t Anker do so throughout? Why copy Beckett so closely and at such length?

Comparing the texts

What about allusive aptness? After all, the ‘borrowings’ occur at a moment when Buys and another character are waiting on a farmer who never shows. This lull makes them attentive to their existential plight and to the received wisdom that blunts a critical faculty. The niggle, though, is that these ideas occur only because of Godot’s presence. They are themselves a received wisdom blunting Anker’s creative faculty:

The acknowledgements

Late to the party, I had started reading the novel towards the end of May 2022, unaware of the earlier accusations. About halfway in – before I noticed the Godot snatchings – I flicked to the back pages. Here I encountered the “Acknowledgements”:

As far as other quotations, references and rewritings are concerned: Omni-Buys saw it all, read every word. He eats as he reads. As he plunders mission stations and cattle kraals, so he plunders the texts of others far and wide in order to tell his own tale. Should you then in his retelling stumble across the remains of other authors, regard it as the homage of a scoundrel.

(I reproduce Heyns’s translation but without mention of Beckett and McCarthy, since these do not appear in the Afrikaans version.) I took this as an ingenious defence of the creative logic that lets the protagonist slip his temporal borders and rove trans-historically.

But after I encountered the Godot pages, it became clear that this insert was a get-out-of-jail card, an authorial self-pardoning. Anker isn’t speaking on behalf of Buys; he’s speaking on behalf of himself.

What to make of it?

There seems to me three ways of responding. The good-faith reader will say, sure, while the Afrikaans text doesn’t cite Beckett, the oversight is corrected in the English translation.

They might add: we hardly expect novelists to declare influences and sources that go into the making of their work. Isn’t intertextual play the beating heart of the modernist tradition to which Buys brings tribute? Half the pleasure in reading a work of literature is that it enlists our participation.

Consider also how Anker takes Godot’s Bible and transforms it to match the wilderness of late 1700s/1800s South Africa, and also Buys’s untamed psyche:

A sceptical reader must agree that this is a fine bit of transposing. But this isolated example shows exactly how minimally other phrases have been changed.

Forget the not-insignificant fact of the missing acknowledgement in Buys. Set aside the puzzling fact that an out-of-copyright addendum receives full bibliographic treatment (a quote from German physician and explorer Hinrich Lichtenstein) while Godot doesn’t. Also disregard the grim view that the Beckett estate is likely to take. You are still confronted with Buys’s baffling disavowal:

It’s as if the stories of others capture something of my own life … the outlines of a conversation, a fly on the edge of my hat, but not the words.

Given the barefaced translation of Beckett that soon follows, “but not the words” reads either as suppression or provocation. Albeit in a different language, it’s exactly the words of Beckett that manifest on the page.

The third position is that of the “ruimhartige” reader. This word occurs in Buys. It’s much more expressively generous than its English counterpart, magnanimity (generosity). To be ruimhartig is to be disposed to complexity – as a principle of compassion but also of intellectual broadmindedness.

Such a reader will respond to the good-faith argument by following it through to its logical conclusion: if Anker declares his debt and wants us to see the presence of Godot, it comes at the cost of his own achievement. For who, following Beckett nearly word for word, would not pale by comparison? Homage to the master means damage to the pupil.

Except, of course, if the homage remains unrealised. By trading on the beauty of Estragon and Vladimir’s exchanges, by drawing from the well of Beckettian despair, and by securing a buy-out through a cover-all acknowledgement, Anker has his cake and eats it too.

A ruimhartige view must also admit the possibility that Anker was seduced by his very seductive creation. Buys declares himself to be a rover, a plunderer. He acts with impunity not only in the world of the novel but across time.

Having written a conceptual “grensroman” (border novel), Anker has been charmed by the idea that boundaries don’t exist. He has spoken the pereant curse without considering that the already-said might come back to haunt him.

Disclosure: While writing this article, the author was contacted by the publisher of Buys, NB Publishers, who requested he submit a report detailing his analysis. This he did as a freelance consultant.

Rick de Villiers does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.