The influence of American music on British acts – and vice versa – is well documented and has been going on since the birth of rock ’n’ roll in the ’50s. The tables were turned in the ’60s with the British invasion, led by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Who. But since the ’70s, it’s fair to say that the influence going back and forth across the Atlantic has been evenly balanced.

In spite of the global cross-pollination of musical influences, there remain acts who are massively successful in their native territories yet fail to achieve very much of note any further afield. Many British acts have achieved almost global dominance yet have failed to score more than a handful of hits, at best, in the United States.

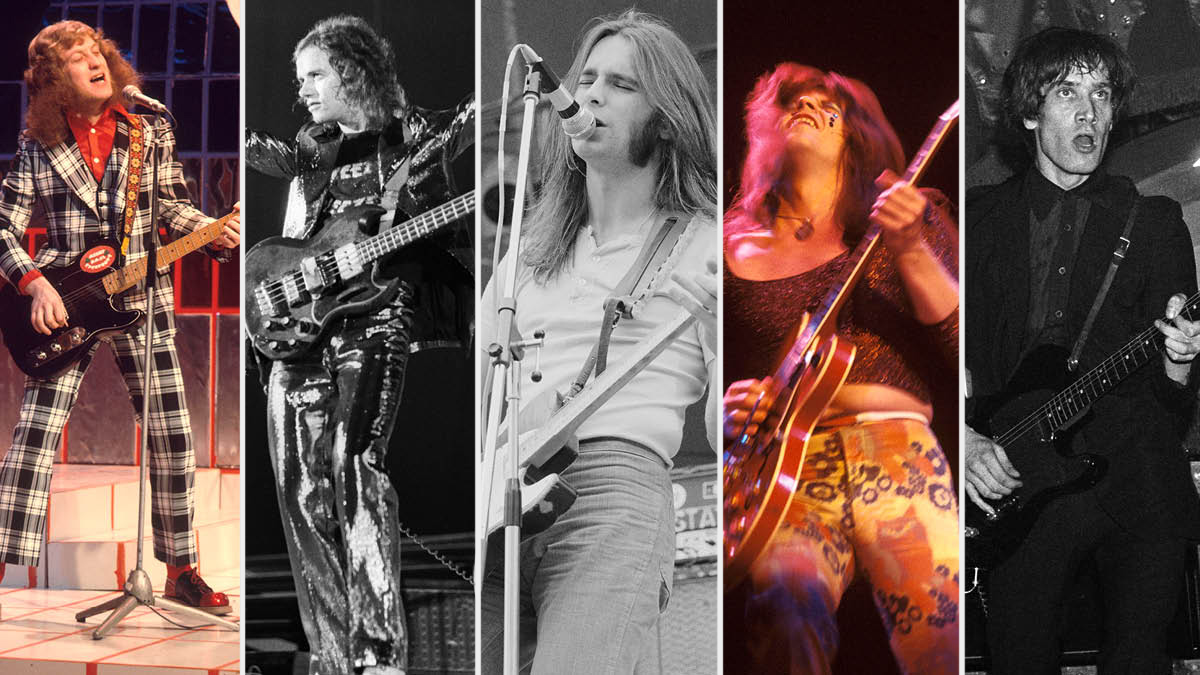

From a sales point of view, the figures speak for themselves: Status Quo are still active and have racked up total sales of approximately 118 million. Slade split up in 1992, having scored sales of more than 50 million worldwide since their first hit in 1970. Sweet were glam-pop superstars in the early ’70s, scoring an amazing run of 16 hit singles between 1971 and ’78, with album sales in the region of 35 million.

Dr. Feelgood’s sales were relatively modest compared to the three previous chart heavyweights, but as precursors to the punk explosion in Britain, they heralded a vital new approach to making music. Songs cut to the bone, running at three minutes or shorter, and with an image that was lifted by numerous punk acts.

Their influence spread across the Atlantic to America, when Blondie’s drummer, Clem Burke, brought their debut album, Down by the Jetty, back to New York with him in 1975. It became glued to turntables at parties with all the prime movers on the NYC punk scene in attendance – and taking notes.

Slade, Quo and Sweet all came up through the same club circuit in the U.K. in the ’60s. They knew each other from the numerous occasions when their paths would cross, and all served their time honing their songwriting chops and learning how to work a hostile crowd.

Dr. Feelgood came up through the U.K. pub rock circuit, which was largely based in London, and saw an explosion of back-to-basics rock ’n’ roll and vintage Stonesy R&B, played in sweaty barrooms to rabid punters, desperate for a fix of something other than the glam pop excesses of the early ’70s or the tired old prog and pomp rock dinosaurs. If this sounds like a familiar tale – the birth of punk – you’re right.

Except for one key point: It wasn’t the likes of the Sex Pistols and the Clash who started that ball rolling; it was the brutal, relentless bands such as Dr. Feelgood, and their contemporaries, Ducks Deluxe, the Count Bishops and Eddie and the Hotrods who paved the way.

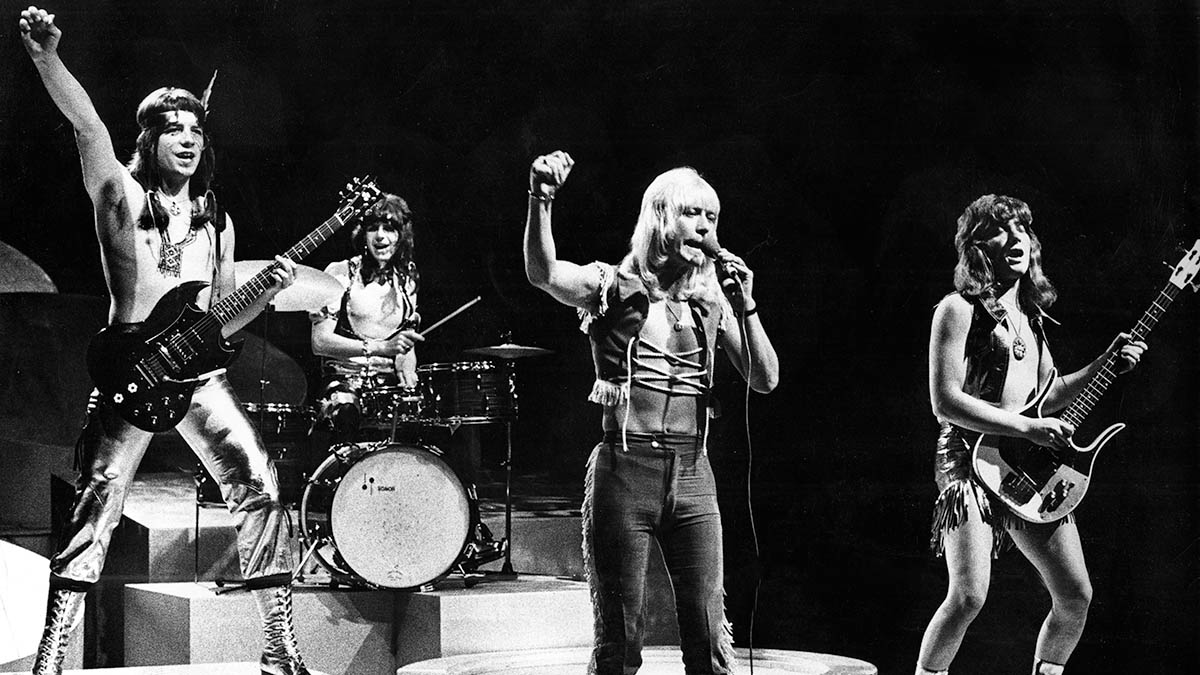

Slade had formed from the coalition of two bands, the N’Betweens and the Vendors. Having released a handful of singles between 1966 and ’69, the band signed to a new label, Fontana, changed their name to Ambrose Slade and released their first album, Beginnings, in 1969.

The album, which was made up of covers of the American hard rock acts such as the Amboy Dukes and Frank Zappa, wasn’t successful, but the arrival of new manager (and former Animals bassist) Chas Chandler, the man who guided Jimi Hendrix to stardom, changed everything.

He took over the reins, instructed the band to start writing their own material and watched them explode into the most successful singles band in the U.K. between 1971 and 1974, outselling everyone from David Bowie to T. Rex. They even became the first band since the Beatles to score a single entering the charts at Number 1, a feat they repeated three times.

The secret to Slade’s success was their songs, penned by singer Noddy Holder and bass player Jim Lea, who was the musical brain behind the band. A virtuoso violinist as a schoolboy, he abandoned the staid world of orchestral ensembles for the hedonistic joys of the three-minute classic.

Lea wrote all the music and often came up with key phrases for choruses and titles, leaving singer Holder to fill in the gaps with bawdy tales and a mirrored top hat full of double entendres…

Piledrivers

Slade made their first earnest attempt to try to break open the world’s biggest market – the U.S. – in 1974. Holder remembers how different the American audiences were from what they’d been used to everywhere else in the world.

“It was a very strange experience,” he says. “Half the audience was out of it; they were just stoned out of their trees. We were an out-and-out rock ’n’ roll band trying to get audience participation going, but the audience just didn’t have any energy. Visually, I think we probably looked like four spacemen up there.” [Laughs]

The Americans didn’t get us at all. Instead of playing to a rabble-raising crowd, all you could smell was pot

Jim Lea

Lea agrees: “The Americans didn’t get us at all. Instead of playing to a rabble-raising crowd, all you could smell was pot. We were really big on getting the crowd involved live. We really made that a big part of our act from day one – maybe we even invented it. When we got to America, no one was doing that, really pulling them in and getting them to be a part of the show, singing and stamping and clapping along. Nod was fantastic at that.”

Interestingly, there were plenty of key figures in the audience taking notes, including future members of Mötley Crüe and Kiss. Noddy again: “Gene Simmons and Nikki Sixx told us they’d seen us live when they were younger. Kiss were a perfect example of taking our thing to the nth degree – people were waiting for a change, and that worked well for Kiss. Then there was the MTV thing, which didn’t exist before. We’d have been perfect MTV fodder.”

Status Quo, to this day one of the biggest bands in the world, had a couple of minor American hits at the tail end of the ’60s with Pictures of Matchstick Men in 1968, six years after they formed in 1962.

That single and its followup hit, Ice in the Sun, were very much of their time – a mix of light psychedelia and pop that bore little resemblance to their later blues ’n’ boogie approach, which has served them well since Down the Dustpipe broke into the U.K. charts in 1970.

Quo realized that all they really wanted to do was wind their amps up to the max and rock out, abandoning the pop elements and replacing them with their own particular blend of heads-down, no-nonsense, boogie. The cover of the band’s 1972 album, Piledriver, tells you all you need to know, without even needing to hear a note of their music.

Quo managed the neat trick of keeping the blues and rock elements of their music real, while also knowing their way around a memorable melody. The riff masters have scored an amazing total of more that 70 hits to date – and counting.

Founding member, guitarist and singer Francis Rossi remembers their first forays into the U.S. circuit. “When we first went to America, I remember we went to this Travelodge in La Brea [in Los Angeles], which was a shithole, really, but light years ahead of what we’d been staying in in England – 24-hour TV, beautiful showers, etc., but the funniest thing was when the phone rang in the room and Rick [Parfitt, rhythm guitarist] and I just looked at each other and went, ‘Fuck, it’s just like on the TV.’ [Laughs]

Everything was almost a little intimidating to a degree – the accents, the full-on confidence everybody seemed to have

Francis Rossi

“Everything about America was so wow, you know? For most bands going over to America in the early ’70s, it was the first time we’d ever been there, so all we knew was what we’d seen on TV and movies. It wasn’t really that common to go to the States for a holiday back then.

“The first time we went to California, we just thought, ‘Wow, for fuck’s sake!’ I loved it, but you certainly wouldn’t have wanted to be poor in California in 1973. [Laughs] What that meant was that everything was almost a little intimidating to a degree – the accents, the full-on confidence everybody seemed to have.

“I think, though, with hindsight, that if we’d had someone based over there, working for us, he could’ve given us a shakeup, maybe said, ‘Come on, you fucks, pull it together,’ you know?”

Rossi thinks that’s one of the key reasons Quo didn’t break the U.S. market. “Our manager told us we needed management in the U.S. When the idea was presented to me back in about 1971, I didn’t realize the importance of having representation in the States and rejected the suggestion.

“Unfortunately, what that meant was that whilst we were getting support and promotion during the time we spent in America, we had nobody working for us at all when we weren’t there. I think that happened to a degree for Slade and the Faces as well.

“There was also the well-known fact in the ’70s that if you wanted to get radio play you very often had to sweeten the deal with a couple of grams of coke for the DJs when you gave them the album – all those kinds of things that we didn’t have in place. I think, looking back, we should have been prepared to give away a percentage of our management for some U.S. representation, [because] if things had taken off, it would have paid for itself many times over.”

The Sweet Life

Sweet were ’70s glam-rock superstars around the world and had more success than Slade and Quo stateside, but nothing like the level they enjoyed in dozens of other countries. They had one of the strongest images at a time when British pop music was overflowing with outrageous, over-the-top acts.

Singer Brian Connolly cut a distinctive figure, and with his long blond hair, he was an instant teen heartthrob. The rest of the band adopted the glam look wholesale, with bass player Steve Priest unafraid to take things to the extreme, even dressing up as a camp Adolf Hitler on one memorable TV performance.

Guitarist Andy Scott, the last man standing, as the three other band members have now passed on, continues to tour with a new lineup of Sweet, playing festivals all over Europe.

Scott remembers that Sweet spurned the first chance they had to crack America for a deliberate career-driven reason. “Little Willy reached Number 3 in 1973, but we didn’t go to America to promote it, as we were advised that if we did, we’d forever be associated with that song, and it would probably limit our future opportunities,” he says. “Following that, Blockbuster just about scraped into the top hundred, but then Ballroom Blitz broke the top 10 again.

“We didn’t travel over to work in America until 1975, when Capitol, our American label, released a different version of our Desolation Boulevard album, which did really well. It included Fox on the Run, which reached Number 5 in the U.S. charts and also included Ballroom Blitz from a couple of years earlier. It made for a strong album as there were quite a few hits on it from the U.K. and America.”

We had quite a big stage show, with films projected behind us, a huge lighting show, a drum solo... and a 6-foot-high penis that would spray the audience when we did our version of J.J. Cale’s Cocaine

Andy Scott

Sweet committed a lot of time to touring America in the mid-’70s. “We did a warm-up show in Seattle then did our first really big date at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in 1975,” Scott says. “It sold out in minutes and there was a huge buzz about us. We got a fantastic response.

“We followed that with a headlining tour. When we were playing America in ’75 and ’76, we had quite a big stage show, with films projected behind us, a huge lighting show, a drum solo where Mick [Tucker] would play against himself on the screen and a 6-foot-high penis that would spray the audience when we did our version of J.J. Cale’s Cocaine. I think if we’d been taking that show out six or seven years later, things could have been quite different for us.”

Nikki Sixx has often mentioned the influence Sweet in particular had on his vision for the kind of band he wanted Mötley Crüe to be – a blond singer fronting a band with three black-haired musicians.

“Yeah. I was told, and I’m not certain it’s true, that when [Sixx] placed the advert for a singer for the band, it said, ‘Glam rock band in L.A. Wanted: lead singer – Brian Connolly, please’ – or words to that effect,” Scott says.

There can be no doubt from a musical and visual perspective that the Crüe of Too Fast for Love (1981) clearly drew a huge inspiration from the Sweet, although perhaps the addition of a hint more metal was the extra ingredient that was required to take them to stadium-filling rockers. That and the push of MTV, which is something Holder thinks could’ve made a huge difference for Slade.

“We were ahead of our time,” he says. “The visuals and everything – we would have been perfect for MTV.” Scott is in total agreement: “MTV would’ve been a game-changer for us when you think about how visual we were, with Brian’s image and Steve’s outrageous visuals.”

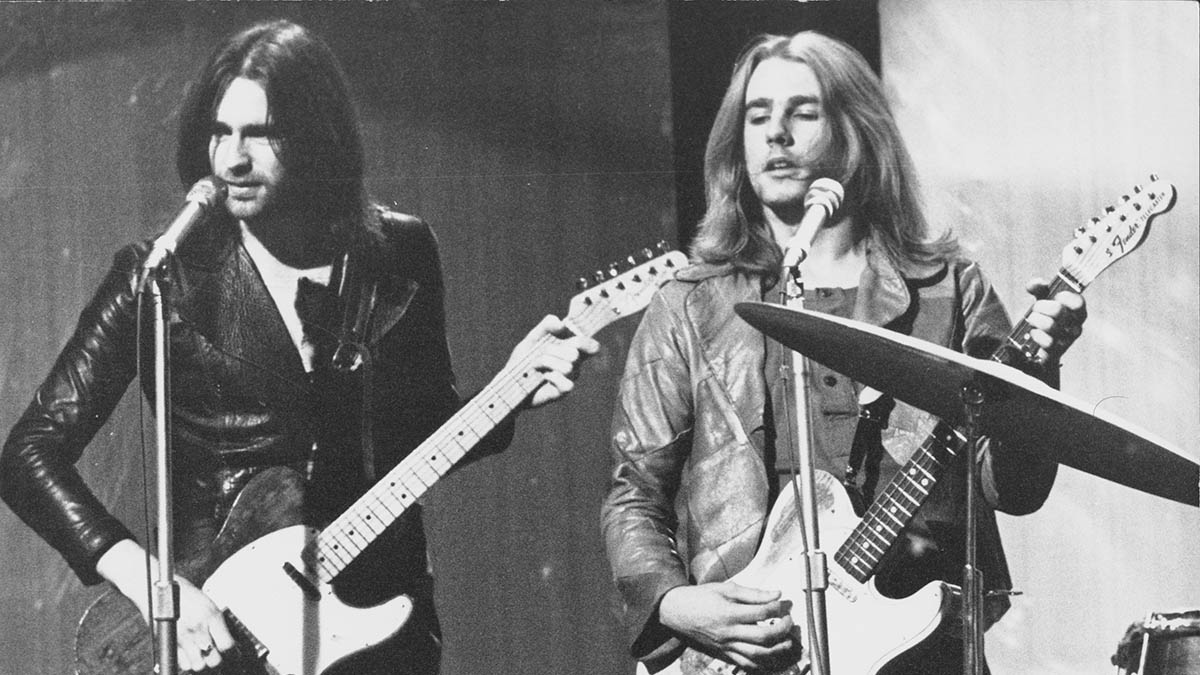

Dr. Feelgood came along after the glam years that saw Slade and Sweet explode into megastars, and just before the punk explosion. The visual chemistry between the band was beyond intense. Lee Brilleaux, who died in 1994 from lymphoma at age 41, had an aggressive vocal style that was mirrored in his image, looking permanently on the edge, ready to do some serious damage to anybody who might want to disagree with him.

Guitarist Wilko Johnson’s feverish darting across the stage would occasionally be punctuated by leaps into the air, and the rhythm section looked like a pair of gangsters from London’s East End. Johnson, who we interviewed not long before his November 2022 death at age 75, recalled that everything was in place for the Feelgoods to crack the U.S. market.

“When we signed with United Artists, our deal was for everywhere in the world except America,” he said. “We were really making an impact and consequently we attracted a lot of attention from some American record labels.

“The key moment was when we played the big party for Led Zeppelin after they’d done their five Earl’s Court [London] shows in May 1975, and Robert Plant had asked if we’d play the huge party afterwards. There were a lot of big names from the American industry there. Ahmet Ertegun was really excited by us and was interested in doing something, and CBS eventually signed us after that.

“We’d released our first album, Down by the Jetty, at the start of 1975 and we’d release our second, Malpractice, at the end of the year. Next thing we knew, we were flown over to their annual convention to play a spot. They were all into us and were planning to really get behind us as a band.”

Meeting SRV in Austin

Plans were set in motion to expose American audiences to the unparalleled might of the live Feelgoods experience. “We actually did two fairly substantial American tours in 1976 after we played at the convention,” Johnson said. “We played all over the States, including the so-called hip venues like CBGB and the Roxy.

“We found, when we got to America, that we were meeting a lot of bands who knew our music and were really into us like the Ramones and Talking Heads. It looked like things couldn’t fail for us. [Laughs]

The thing about Down by the Jetty was I fought for us to play it live, in the studio, with no instrumental overdubs, and I also insisted we do it in mono. My ego was unrestrained at that time

Wilko Johnson

“I remember we did get to see some of our heroes. I saw Jimmy Reed at Antone’s in Austin with the Fabulous Thunderbirds backing him. I remember meeting Jimmie Vaughan’s brother, Stevie Ray, who said, ‘Aren’t you in Dr. Feelgood?’ and asking us about Down by the Jetty, being amazed that we recorded it in mono.

“It kind of showed the reach that album had. The thing about that album was I fought for us to play it live, in the studio, with no instrumental overdubs, and I also insisted we do it in mono. My ego was unrestrained at that time. [Laughs]

“Once we’d just released Stupidity, our live album that went straight to Number 1 in the U.K. in 1976, CBS wanted us to make our next album, which would turn out to be my last for the band, Sneakin’ Suspicion, with an American market in mind. They found us an American producer, Bert DeCouteaux, who’d worked with a lot of great artists.

“They didn’t release the first three albums, so the intention was to launch us with Sneakin’ Suspicion to the American audience. We were getting a fantastic response everywhere we played in America. I can remember when we played the Bottom Line in New York it was exceptional.

“I think our timing was perfect, getting in on the punk/new wave movement; we’d been influential to both in the U.K. and, it turned out, in New York as well.”

Inter-band problems and some unfortunate management decisions started to undermine the band, and surefire success started to look like a distant dream.

“One part of one of our tours was where we were supposed to support Kiss at a stadium show in Mobile, Alabama. We weren’t fans of Kiss at all. [Laughs] Something happened at the venue with our manager and the band or their management, and he came back to tell us we weren’t doing the show.

“I remember CBS turning up and their guy was absolutely beside himself – he couldn’t believe we were pulling out. [Laughs] The funniest part of that experience was that our next date was scheduled for Memphis, and I was sitting there pondering the whole fuckup when I realized, as a huge Dylan fan, that I was stuck inside of Mobile with the Memphis blues again.” [Laughs]

Things took an even worse turn soon afterwards. “Unfortunately, things weren’t happy in the band. I was freaking out a bit because we were doing all this touring, but I was also under pressure to come up with the songs for the fourth album. There was a lot of friction in the band, and the divide came down to the rest of the band against me.

“Everything was boiling over when we were recording Sneakin’ Suspicion at Rockfield Studios in Wales. Things came to a head when they were all drunk and doing coke and I was speeding, and by the morning it came to the point where they threw me out of the band.

“Naturally, CBS were freaking out then, as they’d got rid of the band’s only songwriter. [Laughs] They’d put a lot of money into us, and they could see everything was falling apart. Everything was pointing in the right direction, but the band imploded. By the time the dust had settled, they had a new guitarist, but the momentum was gone, and I formed a band called the Solid Senders, which I don’t have fond memories of.”

Coincidentally, at the same time Dr. Feelgood were attempting to make headway in America, Slade had decided to spend a couple of years living there, thinking the only way to really make an impact was to apply the same intense touring workload that had enabled them to dominate the U.K. and most of the world.

Holder: “Our U.S. manager said we need to spend more time touring the States, so we made that decision to spend two years of solid gigging in America.

It improved us as a band because we had to work hard to win over U.S. audiences in some areas, but we really were the wrong sort of band for a lot of places. The East Coast and Midwest were great, but the West Coast was just too laid back, too much into the singer/songwriter vibe. We were considered too heavy for AM radio, but FM was playing our album stuff, which was weird as we were considered a singles act.”

Quo and Slade played some dates together in America in the mid-’70s. Noddy remembers: “Francis Rossi said that if we weren’t careful we’d end up losing our home audience. He told me that Quo were going back to the U.K. because it seemed too risky to endanger their success everywhere else for the sake of cracking America.”

We thought what if we spend X years chasing that American dollar and we don’t break through, we could end up losing some of what we already had

Francis Rossi

Rossi remembers the conversation: “I did think there was a danger of them losing their core support if they spent too much time away from the U.K.” In fact, Slade’s sales and chart placings did start to slip at that time, but whether that was due to their absence or just the changing tastes of a fickle record-buying public is impossible to say.

“I remember the notion was that you’d work a territory back and forwards and then move on to another then consolidate what you’d done,” Rossi says.

“I was looking at a map of California and I thought we aren’t even going to live long enough to do justice to California – it’s that big. [Laughs] We had a discussion as a band that we were doing really well everywhere else in the world, making great money, that we thought what if we spend X years chasing that American dollar and we don’t break through, we could end up losing some of what we already had.”

When Status Quo opened up Live Aid in 1985, it seemed the perfect chance to try to capitalize on their higher profile. Rossi recalls: “Live Aid didn’t make any difference. We didn’t even really want to do it, so we just said we’d go on first to get it out of the way, but ironically, that opening clip was what got shown all around the world time and again on news channels.

“It didn’t have any impact on our sales – not that we were doing it for that reason anyway – we just did it as a favor. If we’d been thinking about capitalizing on opportunities I suppose we could have done some stuff in America on the back of it, but that never entered our minds.

“Having had this discussion, though, you’ve really made me think whether we should have gone back and tried to have another go at America. I know there are a lot of bands in America, rock and punk, that have told me they really liked what we did, and I always have to ask them how they even knew our music.” [Laughs]

Slade returned to the U.K., having to finally admit defeat on their quest to replicate their worldwide success in America. They found that the changed music scene in the U.K. in the mid-’70s, with the U.K. in the grip of punk, wasn’t as welcoming as the scene they’d left a couple of years earlier.

“I don’t know if it was our absence, or just that things had changed so much in the U.K.,” Holder says. “There was a whole disco explosion as well, which really wasn’t something that had anything to do with a band like Slade.” Lea agrees: “I think that’s right, in a way.

“When there’s musical uncertainty it always seems to turn to dance music. With a band you get a group of guys together with personalities, you know, but the dance/disco thing was very producer-orientated. Things weren’t noisy anymore. The Bay City Rollers did really well in the U.K. and in America, and I suppose they kept a small bit of that glam spark going – but tastes did change.”

Sweet found that while they had a degree of success in America, sales back home were slowing down for them as much as they were for Slade. Unfortunately for Sweet, relationships in the band also started to fall apart, which hastened their demise. Connolly left in 1979, which was a hard blow to sustain, but then when Priest left in 1981, it caused the band to temporarily split.

“Ed Leffler, who was a well-known figure who’d worked with the Beatles and the Osmonds (and later Van Halen), managed us when Desolation Boulevard came out and we were doing quite well, really,” Scott says.

“What he said, we did, because we had a lot of faith in him, but that ended up to our detriment, because by the end of the decade we had fuck all left in our pockets because we’d spent too much money touring. We tried to pull things together again a few times over the years with Steve, but he never really wanted to commit to playing.”

Having had this discussion, you’ve really made me think whether we should have gone back and tried to have another go at America

Francis Rossi

If there is a common theme amongst why Slade, Sweet and the Feelgoods didn’t take America by storm in the way that they’d become accustomed to elsewhere, it seems to be a matter of bad luck – or simply bad timing.

For Slade and Sweet, the arrival of MTV 10 years sooner was probably all it would’ve taken. For the Feelgoods, relations had deteriorated too far by the time the opportunity arrived. For Status Quo, a pragmatic decision was taken that has perhaps been proven to be the correct choice with hindsight, as they continue to fill stadiums around the world.

Rossi is somewhat rueful when he looks back, though: “I think, again with hindsight, that it was probably a mistake to opt out of trying to crack America and continue to work the rest of the world.

“I guess we possibly worked the other markets where we were doing very well to death, but it’s easy to look back and see what you should have done differently. We were doing exceptionally well everywhere else, and of course we all had families, and security is important to some degree, and we decided to take things the way we did.”

The four bands discussed here are arguably the four most important British bands to fail to really make an impact in America, but there are many more acts worthy of further investigation, including the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, Wizzard, Cockney Rebel, Mud, Japan, the Jam, Ian Dury and the Blockheads, the Stranglers, the Buzzcocks and the Specials, to name just a handful.