“The steaks trailed smoke when they brought them out,” says Billy Joe Martin, who watched the sirloins emerge from the kitchen hissing and steaming, like a locomotive, a bovine train now transporting him to another time, another place.

Billy Joe and his father always sat at the bar at Steve’s Sizzling Steaks. Even the name comes out hissing. From his stool in that wood-paneled room in Carlstadt, N.J., on the Route 17 run-up to the George Washington Bridge, Billy Joe could look past the bartender to two framed photographs on the back wall: one of Babe Ruth and one of Billy Martin, the manager of the Yankees. There were other photographs, of other famous people, on other walls. “But behind the bar,” says Billy Joe, “there were just two: Babe Ruth and my dad.”

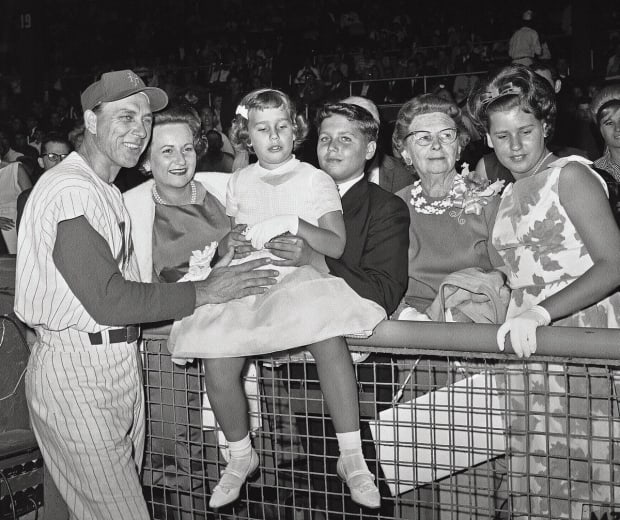

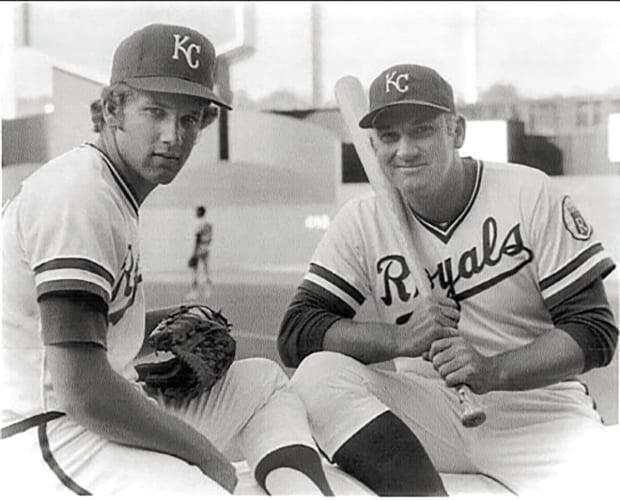

Courtesy of the Killebrew Family (Killebrew); Jim Kerlin/AP (Hodges); Courtesy of the Martin Family (Martin); Bettmann/Getty Images (Killebrew)

Whenever Billy Martin and Billy Joe went to Steve’s, owner Steve Venturini appeared, summoned by staffers whispering on the phone that the skipper was in today. “Tell Billy Joe about the Babe,” Billy Martin would say to Venturini, who took over the steak joint in 1936 and became a fishing buddy of Ruth and Ernest Hemingway. The stories were really for Billy Joe’s father, who was star-struck by only one human being. “My dad had a man crush on the Babe,” he says.

As their steaks sizzled, father and son listened to Venturini describe the great man’s Ruthian appetites, his preferences in steak, beer, whiskey and waitresses, how the Babe would wake up in a steakhouse booth at 6 a.m. to go fishing with Steve, then get dropped at the dock in time to hit two dingers at Yankee Stadium. Billy Joe sat enraptured in the dark room, as if in a movie theater, a boy literally looking up to bartenders and ballplayers, in the only childhood that he knew, which was the world of Major League Baseball. He was belt-high, like a bad fastball, but spending his summers with the Bronx Zoo Yankees.

“I was 12 years old,” says Billy Joe, now a 57-year-old man who goes by Billy Martin Jr. “I was just going to the shop with my dad.”

Irene Hodges was 18 years old when she visited her father at his shop in New York City on a fall day in 1969. A raucous workplace celebration was underway. The firm managed by Irene’s dad—the Mets—had just won the World Series. Irene and her 19-year-old brother, Gil Hodges Jr., braved the crossfire of champagne corks to get to their father’s office, where the silent phone on Gil Hodges’s desk drew the attention of their mother, Joan.

“Gil,” Joan told her husband, “you should call your mother.” Gil’s mother was at home, watching the celebration on TV in Indiana, where Hodges began his long journey to secular sainthood, first as a Marine in World War II, then as a beloved member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, then as a player for the original Los Angeles Dodgers and the original New York Mets, and finally as manager of those Amazin’s.

Gil thought for a moment and said: “That’s a long-distance call. I think I should make that one at home.”

Irene Hodges is now 71 and living again in the house where she grew up, in Flatbush, where she’s caring for her 95-year-old mother. It’s the same split-level to which Gil Hodges returned in the 1960s after managing the Mets, in the same borough where he played first base at Ebbets Field, 75 feet from Jackie Robinson, once upon a time. “He used to walk to the stores around here,” says Irene. “He was part of the church, part of the community, did the same things anyone else would do. He’d go to the butcher, go to the supermarket. People would shake his hand, put an arm around him and say, ‘Hey, Gil, how are you? Good luck tonight; we’re rooting for you.’ It was never intrusive, never threatening.”

It was a 20-minute drive home from Shea Stadium on that crisp Thursday afternoon 53 years ago, and Irene is now thinking of the lost world it betokened—of long-distance calls, rotary-dial phones, World Series day games and baseball at the center of attention. All of it has long since passed from this world, as has her father, but that day in 1969 keeps his memory alive. “He had just won one of the biggest World Series in New York history,” Irene says of that phone call to her grandmother. “But that didn’t change the essence of the man. He was still going to do the right thing.” In his moment of professional triumph, Gil Hodges called his mother from home. Says Irene: “That’s the perfect story of who my father was.”

He was a man who never swore, at least not at home. (“He probably did in the clubhouse,” she concedes, and perhaps in combat in Okinawa.) He didn’t countenance lying. (“There was no coming back from that,” she says.) She traveled to Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Fla., for spring training every year. “We played with Carl’s children, Jackie’s children,” she says, referring to Furillo and Robinson, the Dodgers of the 1950s, immortalized as the Boys of Summer. “It was a wonderful time to grow up.”

AP

These are the boys and girls of the Boys of Summer, the grown men and women who were children in a golden age of baseball in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, who had a child’s-eye perspective of the game and its trappings, for better and sometimes for worse. And like most adults who have lost a father, regardless of how many years have passed, they miss their dads.

Harmon Killebrew, who frequently brought his sons, Cam and Kenny, into the Twins’ clubhouse, drew them aside when they were still boys and said: “You’re gonna hear a lot of things and see a lot of things in here, but that’s not the way we talk or act. It’s just ballplayers letting loose.”

“And we did see and hear a lot of things,” says Cam. “A lot of swearing and a lot of horseplay. It was just a different way of growing up.”

Billy Joe Martin was sitting in a locker in the Yankees’ clubhouse on the road when Dave Winfield, wearing only sandals, walked past. Billy Joe peered over a magazine at the 6' 6", 220-pound exemplar of athleticism. The Yankee in the next locker lowered his newspaper, too, and watched Winfield walk to the shower. Yankees scout Gary Hughes had told Billy Joe the key to evaluating baseball players: “Trust your eyes.” Unknown even to himself, Billy Joe was already trusting his eyes. “Winfield was one of those guys, like Deion Sanders, your eyes just went to him,” he says. “You could spot them from the upper deck.”

Kenny Killebrew found freedom in the upper deck or any other cheap seats. He usually sat behind home plate at Twins games when he wasn’t working in the commissary at Metropolitan Stadium, making the food the vendors sold. Kenny couldn’t eat that food. He and his siblings were raised on a strict diet: no sugar, no caffeine, no candy, none of the things on offer at the ballpark where his father played third base. At home, Harmon Killebrew made wonderful ice cream with peaches or raspberries. He made root beer sweetened with honey. But Kenny, like every other kid at the park, craved a Coke and a hot dog.

So occasionally he’d sneak to the stadium’s less desirable seats, where he’d enjoy an illicit Frosty Malt, an ice cream confection whose circular lids could be thrown like Frisbees. Those lids littered the warning track, calling out to Kenny in his seat behind the plate. On June 22, 1971, against the visiting A’s, Kenny absconded to the left-field bleachers. He’d never sat in them before—right field was his junk-food refuge—but in the bottom of the sixth inning on that Tuesday night he was there sneaking a hot dog as if it were a cigarette when his father connected on a pitch from Daryl Patterson. By some small miracle of fate, aided by the Twins’ abysmal attendance, 13-year-old Kenny caught the 498th home run of his father’s career.

Ecstatic, Kenny raced to the top of the tunnel that led from the dugout to the clubhouse, where security knew him. Harmon was summoned by a guard in midgame. The slugger put his massive hands on his hips and said with a singsong note of suspicion: “What were you doing out there, Kenny?”

“He knew,” says Kenny. “He knew.”

Forty-nine long days later, on Aug. 10, 1971, Harmon hit his 500th home run, then only the 10th man to have done so. Sometime in the hours that followed, Cam answered the home phone, tethered to the wall by 50 feet of coiled cord: “Killebrew residence.” An operator asked the teenager whether his father was available.

“Who should I say is calling?”

“President Nixon.”

Courtesy of the Killebrew Family

In startling ways, the children of baseball were confronted by their fathers’ fame. Teenage Ken Killebrew was driving with Harmon from Los Angeles to Idaho and stopped at the Golden Nugget casino in Las Vegas for sourdough pancakes. “We go in, we’re having pancakes, and I see Robert Wagner,” says Kenny. Wagner so frequently appeared on the console TVs of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s that his Zenith-framed face was like a family portrait in many American homes. “So Robert Wagner comes over and says, ‘Harmon, how you doing?’ ” Ken says. “And my dad stands up and says, ‘Hey, Bob, good to see you.’ ” Ken howls. “Bob. And I’m like, You gotta be s---ting me.”

Cam Killebrew played baseball at BYU. He was having lunch with his parents at the Sundance ski resort when Robert Redford walked over and introduced himself. “Harmon,” Redford said, “Big fan.” Harmon, ever polite, told Bob he’d seen all his films.

Hall of Fame baseball players and A-list actors were kindred spirits in many ways. For more than 20 years, Telly Savalas lived in a third-floor suite at the Sheraton next to Universal Studios, where he filmed Kojak in the 1970s. He watched so many ballgames at the hotel’s bar they eventually renamed the joint Telly’s. His love of the game drew him to Harmon’s charity golf tournament in Idaho, where the two developed a friendship. They were two of America’s most famous bald men, accustomed to room service and pillow mints, and remained close until Savalas’s death, in his suite at the Sheraton, in 1994. Harmon and Savalas once vacationed together in the Philippines. “They probably wouldn’t be too proud of it now,” says Cam, “but they met Ferdinand Marcos on that trip.”

Kleptocrats, Kojak, cowboy actors, all the biggest Bobs—they were drawn to baseball players when athletes, politicians and fictional gumshoes dominated the three-network monoculture. “I met James Garner of The Rockford Files when he played golf with my dad,” says Irene Hodges.

Billy Joe Martin was 9 when General Patton knocked on the door of his family’s hotel room in the Bahamas. It was actually the movie star George C. Scott, filming The Day of the Dolphin on Abaco. “He was a baseball fan who wanted to meet my dad,” says Billy Joe. “That kind of thing happened all the time.” Billy Joe went to the set and sat in the director’s chair. The memory endures nearly half a century later. “I got to pet the dolphin,” he says.

Baseball was not just a show but The Show, entertainment on the grandest scale. Irene’s birth was on the front page of the Daily News in 1951, six months before the Giants’ Bobby Thomson hit history’s most famous home run, against the Dodgers. Irene’s dad began the long walk from first base to the center-field clubhouse at the Polo Grounds before Thomson made it to first base.

On a Tuesday night in 1977, 14-year-old Billy Joe Martin went to visit his father at his office. Billy Joe watched Game 6 of the World Series from his seat near the home dugout at Yankee Stadium. That summer, the Bronx had burned with urban fires. New York City endured bankruptcy and blackouts. Billy Joe and his mom, Gretchen, stayed at the family’s offseason home in Texas most of the so-called Summer of Sam. But now, as Reggie Jackson hit one, then two, then three home runs on consecutive pitches, the teenager couldn’t imagine being anywhere but the Bronx. A security guard told him, as the evening wore on and a joyful menace suffused the air, that he needed to get to the clubhouse for his own safety. “But I didn’t want to miss the show,” he recalls. Fans tore up sod and snatched other holy relics—caps and jerseys—directly off the fleeing Yankees. Cops swung batons as Billy Joe scampered to the clubhouse. “It was awesome,” he says. “I had my first champagne that night, with Willie Randolph’s little brother.”

So many of their memories are sensory: tastes, sounds and smells. Cam Killebrew’s earliest baseball recollection is walking into Griffith Stadium in the nation’s capital as the 5-year-old son of the Washington Senators’ slugger: “Colorful signs, cigar and beer smells, a lot of green painted wood. Comiskey Park had that same green paint.”

Billy Joe remembers the very moment he realized what a privileged world he had entered: as a teenager, in a Yankees uniform, shagging flies at Fenway Park while wearing Thurman Munson’s catcher’s mitt. A batting-practice ball hit the Green Monster and made that distinctive thunk. The carom of the baseball was like Newton’s apple falling from a tree. “It all hit me right there,” says Billy Joe. “Wow, man, Babe Ruth used to run around this outfield. And the DiMaggio brothers, and Ted Williams, and the Mick. I got goosebumps. My knees were wobbling on the next fly ball. Holy cow, I’m lucky.

Cam Killebrew was sitting in the Twins’ dugout in Minnesota when his dad called him to the batting cage. “Mickey wants to say hey,” Harmon said. Mickey Mantle came out of the cage, called for a baseball from the BP pitcher, asked a reporter for a pen and wrote: TO CAM, YOUR FRIEND, MICKEY MANTLE. “I was 12 years old,” says Cam. “I still have the ball.”

Courtesy of the Martin Family

But baseball dads were gone when other dads were home: nights and weekends. “I wish my dad managed the Texas Rangers,” a boy told Billy Joe when he was a kid in Arlington, and Billy Joe replied: “Sometimes I wish my dad worked for General Motors.”

Billy Martin saw Billy Joe play one game in four years of high school. The man famous for his brawls and his temper was managing the A’s, who were playing in Arlington that night. His presence was soothing to his son. “My father never yelled at me,” says Billy Joe. “Never. He went out of his way to show me love and support because he knew he couldn’t be there all the time. He had the ability to turn it on and off. I think he had to, to keep from going totally crazy.” Billy Joe hit the first pitch he saw that night to the wall and went 5-for-5. It was the best game of his career. His taskmaster coach didn’t ride him that game. “He was probably worried my dad would beat him up,” says Billy Joe.

Harmon Killebrew came to only one of Cam’s high school games, and in that game the boy, who hadn’t whiffed all year, struck out looking. Cam still maintains it was a bad call, and he said so at the time to the umpire. Harmon called his son over immediately. “You will never argue with an umpire again,” he said. Cam never did.

When the Dodgers left Brooklyn for L.A. in 1958, the Hodges family moved with them. Irene was 7. She made her first communion in California. They rented a house in Long Beach, but Joan Hodges, a Brooklyn native couldn’t adjust to the palm trees and sunshine and surf. Joan Lombardi was a Dodgers fan before she met Gil. She was working at Martin’s department store on Fulton Street when her friend and coworker Peggy mentioned that her apartment building on Pacific Street had just gotten two new tenants: Gil Hodges and Eddie Miksis of the Dodgers. “Peggy knew that my mother loved the Dodgers so much she used to skip school to go to the games,” Irene says. Peggy invited Joan to her building. Joan Lombardi became Joan Hodges.

Like any Brooklynite, Joan was heartbroken when the Dodgers, and the Hodges family, moved to Los Angeles. “My mother had never been that far away from her parents,” Irene recalls. “She wouldn’t even unpack.”

And so the Hodges family stayed in Flatbush the following seasons, visiting Gil in L.A. over the summer. In 1962, Irene’s father signed with the expansion Mets but moved to Washington, D.C., a year later to manage the Senators. She wept. “You want to eat, don’t you?” Joan asked Irene by way of consolation.

“She’s an Italian mom from Brooklyn,” Irene says. “It’s always about food.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

They’re friends now, these children of the game. Like the leather laces of a glove, some are tight, some are loosely tied, but all are bonded by baseball. Among their acquaintances are familiar surnames: Kelly Drysdale. Roger Maris Jr. The Mantle boys. Irene lost touch with the children of the Dodgers diaspora but not with the former president of the Gil Hodges Fan Club. Sixty years after 15-year-old Joann Duffy of Long Island organized Gil Hodges Night at the Polo Grounds, she and Irene remain Facebook friends. “As I got older, I very rarely told anyone who my father was,” says Irene, whose closest friends remain her grade-school classmates. “They either had to ask me or they never found out.”

This discretion is familiar to any child of a famous parent. Billy Joe was a student at Texas Tech in 1986 when he was asked to appear on a new talk show, for a segment called “Children of Controversial Figures.” On a lark, he allowed producers to fly him to Chicago, where he met Bobby Knight’s son on The Oprah Winfrey Show. They hit it off. “I instantly bond with other children anytime I meet ‘The Son of . . . ,’ ” says the son of Billy Martin.

When George W. Bush owned the Rangers and was merely the son of the president of the United States—and not yet president himself—he gave Billy Joe a bro hug at a ballgame. They’d never met before but appeared to share some secret knowledge. Billy Joe realized, “I might have a little bit of an idea of what it’s like to be the son of the president.”

Indeed, there is now a club for the progeny of former U.S. presidents. The Society of Presidential Descendants is a year-old, invitation-only association whose mission is “to share a camaraderie” among this unique cohort, which is also what these baseball descendants like to do. Feeling their own mortality and, in this lockout-delayed season, the mortality of the game they love, some of these friends talk about starting a podcast, writing a book together or forming their own fraternal order to keep alive their own memories, and those of their parents. “It’s such a pleasure as adults to talk to each other about how cool our dads were,” says Ken Killebrew.

Not all baseball kids are the children of ballplayers. The circus has many performers. Billy Joe met Dave Pepe in 1975 when both were newly minted teenagers at Yankees spring training in Fort Lauderdale. They were the blue-collar baseball kids in a school full of children whose wealthy parents wintered in Florida. Dave’s dad, Phil, covered the Yankees for the Daily News. The boys bought their first vinyl LPs together that spring—ZZ Top’s Fandango! and Nazareth’s Hair of the Dog. Billy Joe and Dave are now business partners, baseball agents who follow the advice Billy Joe got as a kid from Gary Hughes in the Yankees clubhouse: “Trust your eyes.”

Courtesy of the Killebrew Family

Mickey Mantle and Billy Martin won four World Series together as Yankees teammates in the 1950s and remained best friends until Martin’s death, on Christmas night of ’89, in a single-car crash in upstate New York. Martin was buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery in suburban New York City, beneath a stone that reads UNTIL WE MEET AGAIN. After his father’s service, Billy Joe walked the 99 paces or so from Billy’s grave to the final resting place of Babe Ruth—“It’s the throw from home plate to second base,” says Billy Joe—and paused over one of the baseballs placed around Ruth’s headstone. HEY BABE, someone had written on it. SHOW THE KID AROUND. Billy Joe was suddenly overcome, thinking of his father and his father’s idol and those adolescent nights at Steve’s Sizzling Steaks.

Billy Joe Martin was a young man, just 25, when his father died and bore a striking resemblance to him. He was working at a TV station in Dallas, where once a month he’d get a call from his dad’s former coworker, inviting him to dinner, which meant asking permission to leave the station in mid-afternoon. Dinners with Mickey Mantle started with cocktails at 3:30 p.m. At one of those dinners, the most famous baseball player of his generation reached across the table, pawed at Billy Joe’s face and said: “Take those damn glasses off.” When Billy Joe removed his glasses, a tear rolled down Mantle’s cheek. Said Mickey: “Now you look like that dago I miss so much.”

Mantle died of cancer in 1995. His sons David and Danny remain close to Billy Joe, bound as children of the game but also as grown men who miss their dads. “Everybody always said, ‘Your dad was a god,’ and everything,” David Mantle told The Oklahoman, in his father’s native state, in 2016. “I think I heard that so much I believed he was God.”

Gil Hodges died of a heart attack at age 47 in 1972. At his funeral, Howard Cosell pulled Gil Jr. out of Our Lady Help of Christians in Brooklyn and led him to a car outside the church. In the back seat was Jackie Robinson. “Hysterical, crying,” Gil Jr. recalled in the 2021 documentary The Gil Hodges Story. “He leaned over, he gave me a hug and he said, ‘Next to my son’s passing, this is the worst day of my life.’ ” Gil Hodges was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery, a mile and a half from the site where Ebbets Field once stood.

For Irene, happy signs—often literal—of her father abound in Brooklyn. She gets a warm feeling driving over the Marine Parkway–Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge into Queens. P.S. 193 is the Gil Hodges School, near a section of Atlantic Avenue called Gil Hodges Way. Fifty years after his death, Irene’s dad will go into the Hall of Fame this month. When Hall chairman Jane Forbes Clark called to deliver the news, she made it as far as: “I’m so happy to tell you…” Irene began sobbing. Then Irene told Joan, “Nobody,” she says, “has waited longer than my mother.”

In the weeks after his dad died, Billy Joe Martin would give his name over the phone to pizza makers or delivery workers, and they would say, “Billy Martin? I thought you just died.” To avoid these exchanges, and to honor his father, he began going by Billy Martin Jr.

Billy Jr. is a father himself to three grown children whose every game and recital he made sure to attend. “I probably went overboard,” he says, laughing.

Years after Harmon Killebrew retired in 1975, his name would pop up in strange pop-cultural contexts. On Cheers, Carla reminded Sam of the time “Harmon Killebrew hit those three moon-shot homers off of you.” David Letterman devoted an entire episode of his NBC show to “Harmon Killebrew Night,” on which no less an authority than Liberace said: “He ranks right up there with Babe Ruth!” Harmon died in 2011, and Cam said that his surname, naturally, is recognized less frequently than it once was. But 30 years ago, Ken Killebrew started a business based on one of his dad’s old recipes, and Killebrew Root Beer remains a fixture in Minnesota, including at Target Field, where kids can shotgun it in bleachers.

The baseball children of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s are now in their 50s, 60s and 70s, but they keep their fathers’ names alive in novel ways. After Ken suffered some health scares, his wife, Mary Jo, bought him a companion dog, a King Charles–Shih Tzu mix named Harmony. Whenever Ken brought Harmony to the dry cleaner or the groomer, someone would ask: “Who do we have here?” Ken always replied, “This is Harmony Killebrew.” He seldom got a glimmer of recognition. Finally, he asked his doctor’s receptionist, to whom he had just introduced the dog, “Have you ever heard of Harmon Killebrew?” She hadn’t. “Have you ever heard of Mickey Mantle?” Ken asked, and she said: “Of course!”

“Well, Harmon Killebrew was my dad,” Ken said, “and he hit a lot more home runs than Mickey Mantle.”

“What can I say?” Ken sighs. “I’m proud of my dad.”