Splattered with bird feces, the family at the center of The Boy and the Heron, Hayao Miyazaki’s new animated masterpiece, can’t contain their joy once they return to 1940s Japan after getting lost in a fantastical, timeless realm somewhere between life and death.

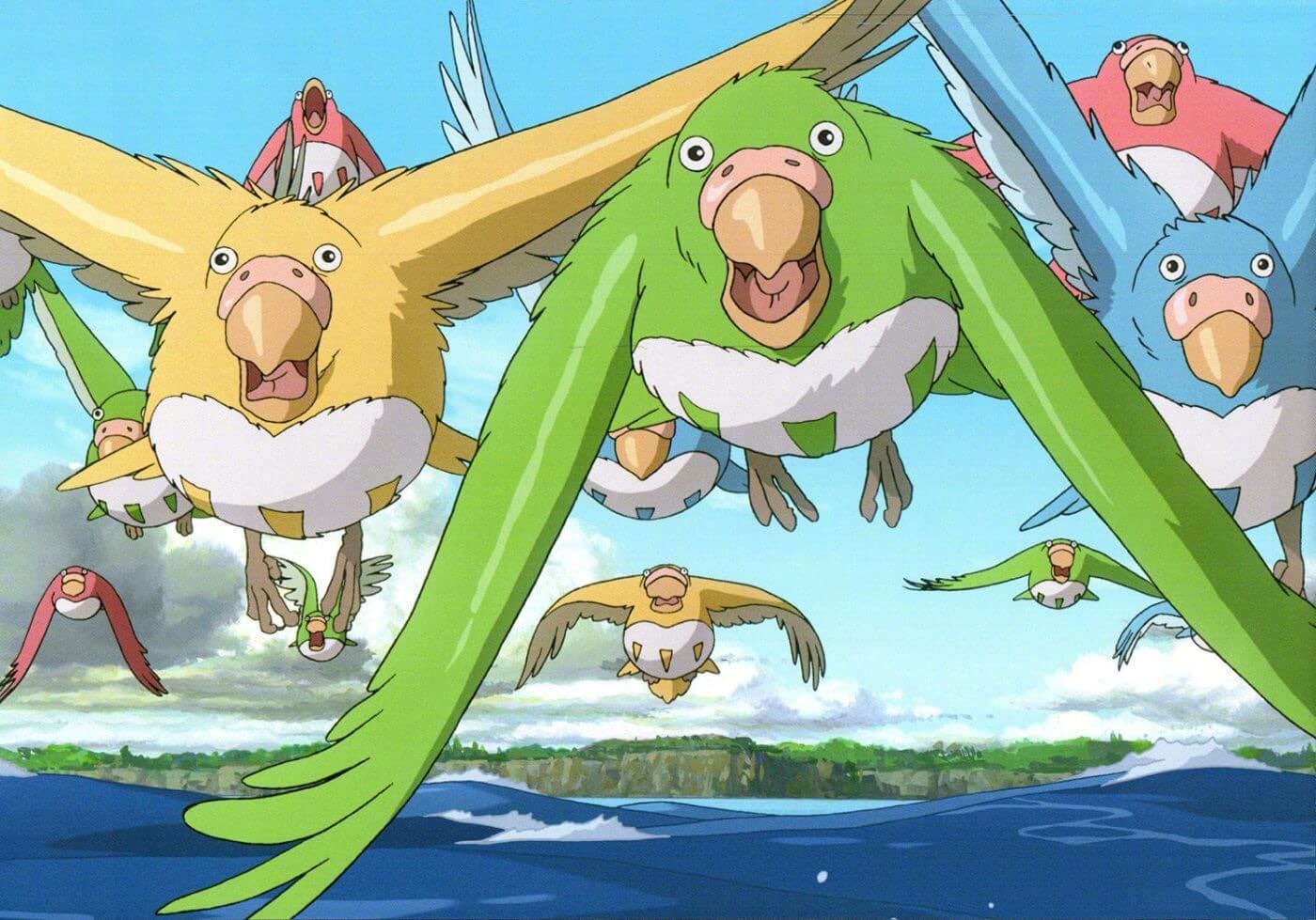

In this transition, a group of parakeets — which just moments earlier were human-sized warriors who could speak — revert to their standard small form upon entering our world. As such, their instinct is to empty their bowels as they take flight.

Nothing in animation is accidental, especially not in the painstakingly crafted works of Miyazaki. And this scatological detail, as off-putting as it could seem, represents a marked differentiation between the “other side” and our reality. In our human timeline, there are hurtful, unpleasant, and even violent experiences we must occasionally confront. But in that moment, the characters ignore the viscous substance running down their faces, quite literally smiling through the shit, happy to be reunited with those they left behind.

Fantasy and reality have always commingled in Miyazaki’s films. For Miyazaki’s protagonists, the fantasy can be a temporary and useful balm for real pain. Yet his heroes and heroines realize the value of life is in living it down here with the rest of us mortals, complications and all. Miyazaki has long tacitly expressed that his wondrous lands are not places for one to reside in but only to visit as a way to learn something about oneself or to overcome a difficult passage.

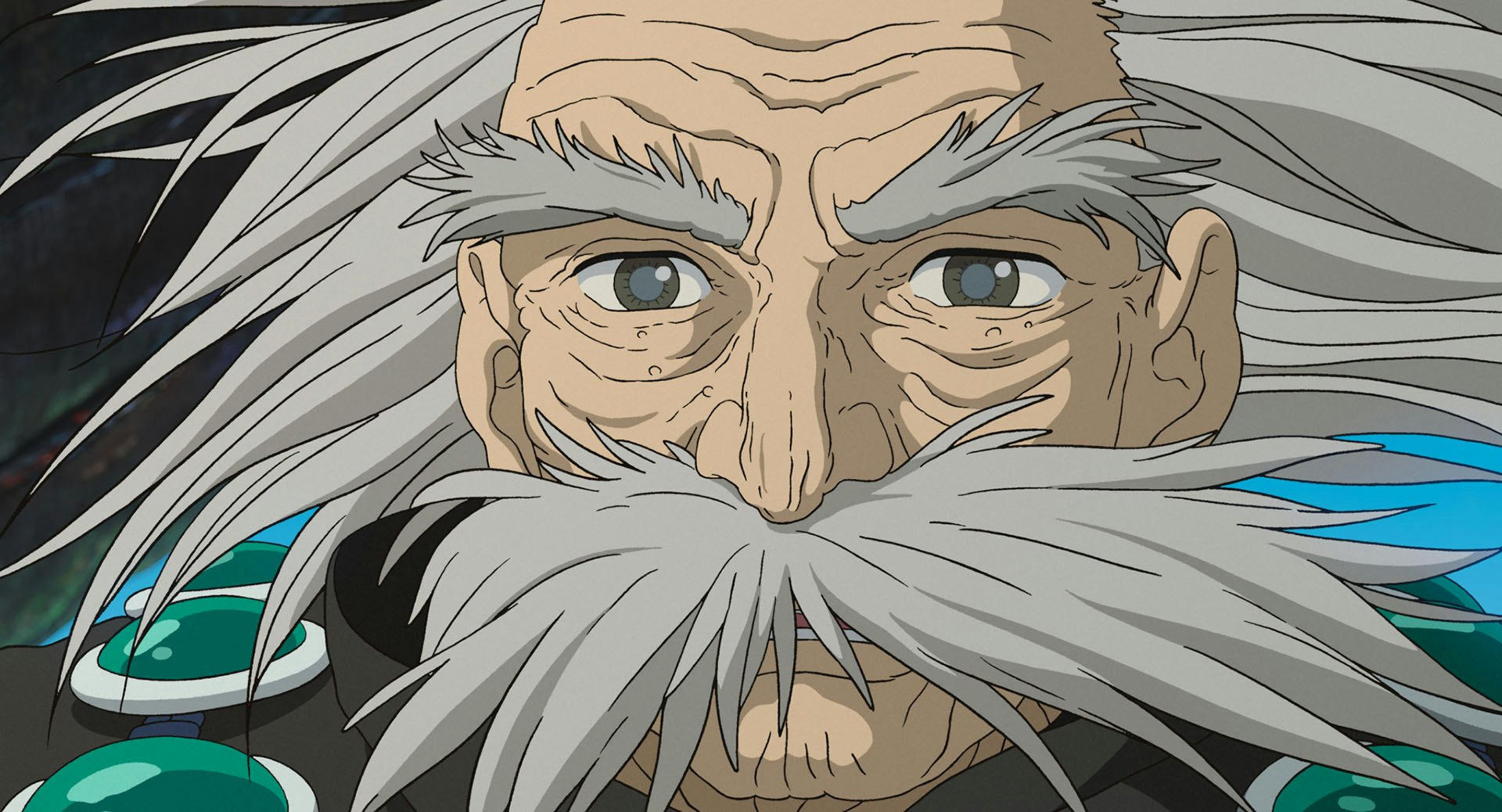

In The Boy and the Heron, this decision to choose a side is made explicit. Even when given the chance to stay and spend time with a younger version of his mother in a breathtaking alternate universe, Mahito, an 11-year-old boy already aware of the suffering of losing someone, still chooses to come back to reality. This puzzles Granduncle, his wise old ancestor in charge of safeguarding the magical cosmos. Having lost sight of who he was before setting foot in the other side, Granduncle can’t comprehend why anyone would travel back to a place plagued with chaos and horror. Perhaps he’s forgotten that amid the devastation, there are glimpses of the sublime. Knowing how a loved one’s absence feels, and understanding someday this separation will inevitably be permanent, is what makes a long-awaited embrace so charged with emotion.

But throughout his past films, Miyazaki has shown how real the temptation of the “other side” is. Extraordinary feats take place in these fantasy worlds, which offer a chance at a blank slate away from the burdens of quotidian agony.

In Spirited Away, for example, Chihiro serves as our guide throughout an otherworldly adventure populated by bewildering friends and foes. But her goal remains steadfast despite the allure of the witch Yubaba’s domain. She must rescue her parents and escape back into the life she knows. The biggest threat she faces is that she could get settled in her new identity and completely lose all memories of who she was once, and even her name.

The experience changes Chihiro in that she gains a new level maturity and a greater appreciation for what she might have previously taken for granted. But the lessons will only prove their importance when she is back with her parents and in her new home.

That Haku, a spirit, has accompanied her since childhood, even if not tangibly, suggests Miyazaki strongly believes the line between both sides, the fantastical and the factual, is not as concretely delineated. Magic is there for as long as you need it, namely — as it’s often the case with protagonists in the master’s tales — during the perilous process of growing up.

That’s also the case in My Neighbor Totoro, where the adorable forest spirits help young Mei and Satsuki deal with their mother’s illness and their relocation to a new town. Or at the end of Castle in the Sky, when Sheeta and Pazu must let go of the floating city. Once the young sorceress in Kiki’s Delivery Service overcomes her tribulations, Gigi, her cat, loses the ability to verbally communicate with her, reinforcing the impermanence of these whimsical lifelines in Miyazaki’s oeuvre. They serve their purpose and then they disappear.

Then there’s porcine pilot Porco Rosso, who at one point considers giving up, enticed by the opportunity of joining with his friends in the afterlife, but instead comes back down to the ground, even if unsure as to whether being alive is worse. And in Ponyo, the titular mermaid-like creature relinquishes her powers to stay on land with Sosuke. Time and again, Miyazaki’s characters, willingly or not, evolve and leave behind the enchantment.

What’s unique about Mahito in The Boy and the Heron is his resolve. Even before he plunges into the unknown, he knows he can’t stay there and that what the other side offers could never replicate the true love of his mother in the time they shared together in our imperfect real world. Instead of the dreamscape, he picks the difficult option: to walk along his stepmother, his father, and his soon-to-be-born brother in our harsh reality.

There’s a moment in the Spirited Away making-of special that succinctly encapsulates Miyazaki’s conviction in the insight we gain from the failures and triumphs of living in the present. As he tries to explain to a group of animators how Chihiro inserting a healing concoction into the dragon form of Haku should look like, Miyazaki is baffled that none of them has firsthand experience feeding a dog medicine. Their work in the film, even if it’s drawing imaginary creatures, can only project truthfulness if it derives it from real life.

For an artist so impossibly gifted at worldbuilding and engendering awe-inspiring scenes, Miyazaki seems to repeatedly tell us that the most marvelous of miracles is in fact our individual bravery to keep on, while knowing that hardship inevitably waits ahead. As his 2013 “final” film eloquently noted by way of a poem, “the wind rises, we must try to live.”