In this series, writers nominate a book that changed their life – or at least their thinking.

Sixty years ago, when the historian E.H. Carr famously asked What is History?, he determined the answer to be a constant dialogue between the present and the past. The past is “what happened”, he explained. “History” is the process of its analysis and inquiry.

The History discipline of Carr’s era is readily recognisable today. The subject we study at school and university is still framed by rules of research and evidence, as well the critical examination of sources and the teaching of skills.

But it has been increasingly pushed and prodded since the 1960s by new methods of interpretation and analysis. These approaches prompted vital historical revisions and asked important questions of the discipline.

If public archives selectively prioritised the histories of leading public figures, as feminist, working class, migrant and Indigenous historians insist, then whose perspectives might have been excluded? Whose voices have we failed to listen to?

They’re questions that resurfaced for me when I first read Tony Birch’s collection of poetry, Broken Teeth, in 2016. I had been working on a history of Australian History, which sought to tell the various ways Australia’s national story had been imagined. But in contemplating Birch’s work, I was forced to reimagine the scope of the project.

To me, his poetry felt as powerful as any of the history books I had been studying, not only with its commentary on “what happened”, but as a statement on historical practice.

Deeply affecting

Broken Teeth includes quiet, sometimes haunting pieces about family, love, and place. We see the texture — sometimes sparse, sometimes richly imagined — of Melbourne, including slices of family life, Merri creek, and chroming kids. It also covers the territory of History, perhaps unsurprising given Birch’s training as a historian at Melbourne University.

There’s a touching tribute to the Japanese historian, Minoru Hokari, who Birch gently farewells in verse, as well as a cool depiction of an anatomy museum that echoes Wiradjuri writer Jeanine Leane’s account of colonial archive-keeping in Cardboard Incarceration.

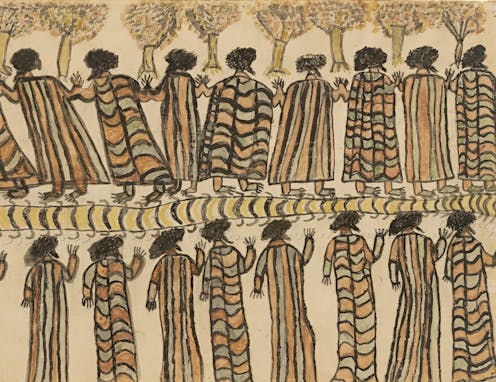

Other pieces relate the history of the Wurundjuri leader, William Barak, who led the Coranderrk mission in the late 19th century and fought for Aboriginal recognition.

But it’s the poem Footnote to a History War (archive box no. 2) that shakes me out of my disciplinary comfort zone. Based on letters between Aboriginal people who were living on reserves and missions and the Victorian government agencies which oversaw them, the “conversation” that correspondence produces is deeply affecting.

Two verses cited here give a sense of what Birch describes as the poem’s “call and response structure” between “the voice of the archive” and “the voice of Aboriginal people”:

iv

my colour debars me

my child is dead

& I am lostwe are broken into parts

our home left in the wind

& it grows colder heremy wife is aborigine

I am half caste

and I am, Sir, dutifully yoursI await your response

v

he wears a suit [issue no. 6]

hat [issue no. 7] & possesses

one pair of blanketsshe has on loan

one mullet net &

two perch netstheir children are gone:

one [toxaemia]

one [pneumonia]one [ditto]

Over ten parts, Birch’s Aboriginal correspondents and their institutional “protectors” paint a harrowing picture of government control and Indigenous desperation. These were lives under constant surveillance and regulation for much of the 19th and 20th centuries. The fact they were assiduously recorded in official archives, but largely absent from Australian History during the same period, is an example of the discipline’s striking hypocrisy.

I can’t help but wonder how I catalogue this piece of work? Is this “poem” also a work of “History”? Can I add it to my canon of Australian historiography? In the end, I do just that.

‘Licking at the edges’

Part elegiac tribute, part stunning critique, Footnote to a History War is an exploration of “the past”, as well as how that past has been archived, parsed, and controlled by History’s gatekeepers.

While its assemblage is creative, taking excerpts and placing them side by side to construct mood, form and shape in a creative process, the poem was built directly out of the archive and its emotion is not confected.

“A great poem cuts through the crap”, Birch writes in the preface to Broken Teeth. That’s exactly what I get from Footnote to a History War. Is it any wonder that the Gomeroi poet and legal scholar Alison Whittaker describes Aboriginal poetry as potent and powerful for the way it “licks at the edges of the colonisers’ language”?

As poetry, Footnote to a History War is both poignant and pointed. As a form of History, moreover, it leads us to confronting truths about the past, and the discipline itself.

Extract from Footnote to a History War (archive box no. 2) appears courtesy of the author.

Anna Clark receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.