In this series, writers nominate a book that changed their life – or at least their thinking.

I’ve always wanted to be a historian. From childhood, I was captivated by the idea of spending my days bringing the past to life. At first, I aspired to be a historical consultant on BBC period dramas. Later, I set my sights on becoming a professor.

I’ve dedicated my adult life to this goal. I jumped straight into studying history after leaving school and never really stopped. Over the 17 years since I was 17, there’s only been a single semester when I wasn’t a student or employee of a university history department.

If right-wing pundits are to be believed, this means my formative years have been spent amidst “cultural Marxists” bent on revolution. In the conservative imagination, humanities departments are where vulnerable youth are brainwashed into a radical leftist agenda. Of course, as those inside higher education know, this is a laughable notion. Today’s universities are neoliberal bureaucracies, profit-driven enterprises more akin to a giant corporation than a cultural wing of the communist party.

Read more: Is 'cultural Marxism' really taking over universities? I crunched some numbers to find out

Yet, it’s also true that, on this continent, the history profession is a self-consciously “progressive” domain. We critique the drum-beating nationalism of Anzac mythology. We’re proud of the discipline’s role in forcing truth-telling about frontier violence. We call for greater care for our environment and question the inequities of capitalism. Feminism is embraced and women loom large among the professional leadership.

All this makes it easy to imagine historians as the good guys, truth-tellers on the right side of history. All this made it easy for me to assume innocence and pretend my own craft of history-making is removed from the bloody histories we interrogate.

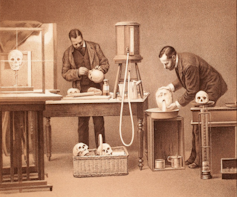

Of course, I’d long known that the university and its pursuit of knowledge was part of the colonial project. I knew archaeologists had stolen Indigenous remains and anthropologists had constructed Indigeneity as a savage Other. I understood that racism was given legitimacy by scientists measuring skulls.

But I stopped short of asking how my own discipline was and remains implicated in this colonising work. A century ago, historians had celebrated powerful white men and omitted everyone else, but surely things were different these days? In the 21st century, History (as a discipline) seemed a benign force, a champion of underdogs and a voice of truth and justice.

Blood on its hands

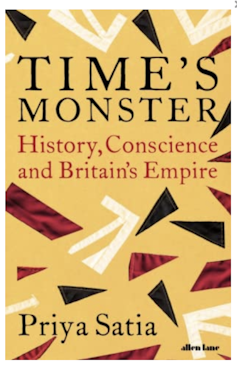

For these reasons, Priya Satia’s Time’s Monster: History, Conscience and Britain’s Empire landed like a bomb in my brain. In this 2020 book, Satia maps how the “historical discipline helped make empire – by making it ethically thinkable”. Far from being innocent observers, “historians were key architects of empire”.

Satia is not the first to identify links between history making and imperialism. Postcolonial historians like Dipesh Chakrabarty argued back in the 1990s that the history profession reflected and reproduced Eurocentric visions of the world.

Yet Satia, an award-winning Stanford professor who specialises in British history, has written the first book-length study that explains exactly how historians helped make empire. In painstaking detail, she shows that History has blood on its hands.

How did this work, exactly?

From the 18th century, historians taught us to understand the world as a story of progress. They popularised the now taken-for-granted idea that time operates as a linear pathway, moving from a backward past towards an enlightened future.

Political philosopher James Mill, for instance, writing in his hugely influential 1818 History of British India, explained that

every society may progress if it chooses, or can be shown how to do so, but it will then follow the same road which advanced societies have taken before it and acquire the same features which everywhere distinguish barbarism from civilization.

Progress is the idea of history as a story of perpetual change and improvement. It is time as a straight line, a highway from darkness to light. This meant that the future would always eclipse what had gone before.

Green-lighting conquest

This time-as-progress thinking gave a green light to conquest and exploitation by making them “ethically thinkable”. As Satia puts it,

[t]he major forces of [modern] history – imperialism, industrial capitalism, nationalism – were justified by notions of progress and thus liable to rationalisations about noble ends justifying ignoble means.

Destruction, violence, suffering – all were excusable because they were stepping stones towards a glorious tomorrow. Thanks to the progress narratives invented by historians, “dreams of utopian ends again and again justified horrific means.”

In other words, my profession forged ways of thinking that enabled the destruction of countless lives – not to mention the unfolding destruction of the planet itself. And although History has become more inclusive and critical of power in recent decades, its foundational assumptions remain largely unchanged.

Even as we expose frontier massacres, academic historians still reproduce the linear temporal scripts that oiled the wheels of territorial expansion and ceaseless economic growth. We remain wedded to ideas about time that made empire “ethically thinkable”.

As a result, History “has yet to come to terms with its role as time’s monster”. Preoccupied with our own embattled position in contemporary culture wars, today’s historians rarely acknowledge that our forebears were not, as Satia writes, “critics but abettors of those in power”. Unlike other disciplines such as anthropology, History has largely neglected to reckon with its own troubled history.

Different notions of time

After reading Time’s Monster, I can’t unsee History’s monstrosity. After 17 years of learning to think like a historian, I’m facing up to the violence implicit in my profession’s way of making sense of the world. It’s a great unlearning, a brain-stretching effort to think outside my established habits of thought.

As a result, I’m opening up to the possibility of radically different forms of history-making. What would it look like for History to truly reckon with and learn from its past? How could we make History anew?

According to Satia, “what is required is not so much progress as recovery from the imaginary of progress”. It’s crucial that we challenge the idea of “directional history” and “recover different notions of time”.

What if, instead of assuming that time tracks along a straight line towards the horizon, we could imagine time as cyclical, as many Indigenous societies already do?

Already there are moves in this direction. In Making Australian History (2022), Anna Clark eschews conventional chronology because it “inadequately incorporates other forms of historical temporalities, such as Indigenous histories that reach across time and space simultaneously.”

New scholarship

However, for different notions of time to truly take hold, white settlers like Clark and myself may need to take a back seat. We can create space for others, we can support others, but surely the beneficiaries of empire cannot ourselves disentangle History from its imperial roots.

Instead we need to look to voices like Margo Neale, whose 2020 book Songlines, co-authored with Lynne Kelly, shares First Nations conceptions of time and archives; Mykaela Saunders, whose 2022 essay Everywhen explains that, for Aboriginal peoples, “all things that have happened are still happening now”; and Samia Khatun, whose 2018 history Australianama is an effort to “take seriously the epistemologies of people colonised by the British Empire”.

Read more: Friday essay: how a Bengali book in Broken Hill sheds new light on Australian history

This new scholarship points to the possibility of making history that challenges rather than supports colonial ways of knowing. But this potential will only be realised if we challenge the whiteness of history-making on this continent.

Yves Rees does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.