In this series, writers nominate a book that changed their life – or at least their thinking.

I am an avid reader and have devoured many books over the years, especially science fiction. For me, reading is about escapism; it’s an opportunity to explore strange new worlds and discover new ideas and new futures.

Yet the book that changed my life wasn’t about far away planets or alien civilisations; instead, it introduced me to a strange and beautiful world that existed all around me.

Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Insects of America North of Mexico by Donald J. Borror and Richard E. White opened my eyes to a hidden world populated by an unimaginable cast of fantastic creatures.

In its pages, I learned about the deeply bizarre “twisted wing parasites” (order Strepsiptera) who live most of their peculiar lives inside the rear ends of other insects; the webspinning Embioptera who collectively weave gossamer nests out of silk they shoot from their forelegs; and the tiny and ultra-enigmatic “angel insects” (order Zoraptera), which live in small social groups beneath the bark of rotting logs.

I learned that the everyday world was full of creatures every bit as bizarre and interesting as science fiction aliens. The Earth was so much more diverse – and weird – than I’d ever imagined.

I first encountered Field Guide to the Insects as a budding biology student who loved searching for creepy crawlies under logs and rocks. I was excited by the prospect that, field guide in hand, I would finally be able to put a name to every single one of the insects I saw on my outdoor explorations.

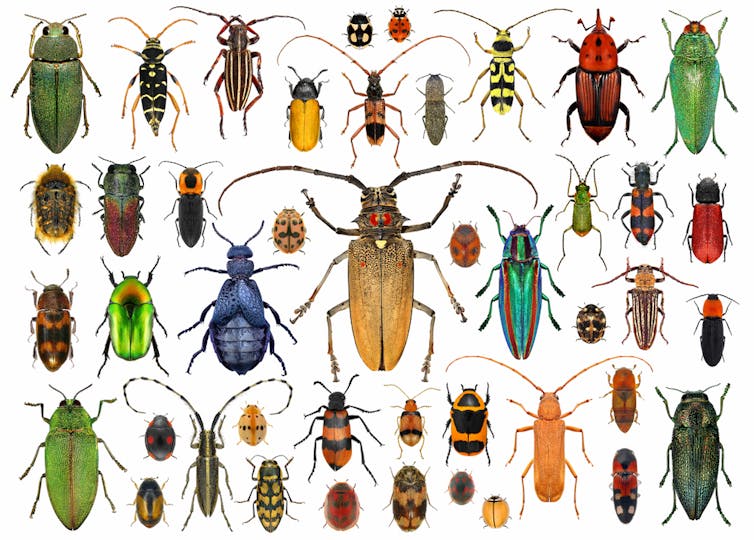

One of the first things this book taught me was how impossible that task was. At the time it was first written (1970), there were 88,600 named species of insect in North America; today, that number likely exceeds 100,000 .

Globally, there are 900,000 described species of insects, making them by far the most diverse group of animals on our planet. Even the most dedicated entomologist would struggle to identify every insect species they encounter; there are simply too many.

À lire aussi : Climate change triggering global collapse in insect numbers: stressed farmland shows 63% decline – new research

Powerful and precious

Field Guide to the Insects navigates the overwhelming number of insect species by focusing on the identification of broad insect groups called “families”. The 1,300 drawings and 142 stunning colour images taught me to recognise the most common insects around me.

I found myself discovering amazing new insects everywhere I looked. The animals I found were not new to science; they were common species, and I had been surrounded by them my entire life. I had just never noticed.

To me, that’s the power of field guides; they help us uncover the hidden diversity of our world. Our little planet is absolutely teaming with a riotous diversity of life forms.

I’ve learned that the knowledge a field guide provides can be powerful and precious. Thanks to a field guide, I know that the leggy spider hanging in my bathroom is a harmless daddy long legs (Pholcus phalangioides) and that the weird caterpillar that looks like bird droppings on my lemon tree will one day become an elegant citrus swallowtail butterfly (Papilio aegeus) .

A field guide taught me that the tiny octopus flashing blue in a local tide-pool was best admired from a distance. At a time when engagement with nature appears to be declining (particularly in urban areas), field guides provide us with the opportunity to connect deeply with it.

À lire aussi : The book that changed me: journeying to the self with Anaïs Nin's sensual, transgressive diaries

From opera glasses to apps

Field guides make specialist knowledge accessible to non-professional audiences; empowering us to explore nature no matter what our background, education or employment.

But prior to the 1890’s, most guides to animals and plants were written exclusively for professional scientists. They used dense technical language to describe often minute differences between specimens, many of which could only be observed as dead animals.

In the late 1800’s two books, Birds Through an Opera Glass (Florence Merriam Bailey ) and How to Know the Wildflowers (Frances Theodora Parsons) became the first modern field guides written for recreational nature-watchers.

Both books featured accessible language and illustrations aimed at helping non-professionals identify plants and animals in the field.

In 1934, Roger Tory Peterson revolutionised the way field guides approached identification with his Field Guide to the Birds. It featured two key innovations: the grouping of similar-looking birds on a single page, and the use of arrows to point out distinguishing features.

The Peterson’s identification system has since been adapted and used by hundreds of field guides.

In recent years, field guides have been joined by automated identification apps such as iNaturalist, PlantSnap, Merlin BirdID and FrogID that use sophisticated algorithms to identify organisms using photos or audio clips. Some apps, like iNaturalist, can identify an enormous range of organisms, far beyond the scope of even the most ambitious guide.

Plants, slime moulds, spiders, fungi

Do these apps replace field guides? I don’t think so. I see apps and field guides as complementary tools that enhance my explorations of nature. Flipping through a field guide helps me to learn the gestalt of features that identifies a group of organisms. Field guides allow for this kind of learning in a way that apps currently do not.

I still have my old copy of Peterson’s field guide , though I rarely use it now. As a professional entomologist, I’ve learned to use more sophisticated identification tools. But I still collect field guides to other groups – plants, slime moulds, spiders, fungi – I am not an expert at identifying.

Field guides taught me to see the world in all its weird and wonderful diversity. Knowing that I am surrounded by a teeming multitude of unique life forms has made my life so much richer.

Tanya Latty receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Herman Slade foundation. She is affiliated with the Australian Entomological Society, the Australasian Society for the Study of Animal Behaviour, and the not-for-profit organisation Invertebrates Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.