If, in early 1965, you were looking for records that stood at the cutting edge of electric guitar, with approaches to the instrument that were years – decades, really – ahead of their time, it's safe to say that you wouldn't have started by looking at the output of Pickwick Records.

The Beatles had taken the stage on The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time on February 9 the previous year, and pop music changed instantly. With good reason, someone looking for guitar inspiration would have started with them.

The Fab Four took the template laid by the rock and roll/rockabilly revolution of the previous decade, and mixed its energy and infectious riffs with immaculate songcraft so good it still boggles the mind almost 60 years later. Guitar sales exploded, and, before 1964 was out, the Beatles were releasing ever-more sophisticated hits like A Hard Day's Night – a chart-topping smash led off by an opening chord complex enough that it took listeners literal decades to fully figure it out.

During this game-changing period, Pickwick Records' catalog was, well, about as distant from these revolutionary sounds as a label could be. Its main concern – aside from its children's and classical music releases – was the budget record industry, at the time a dreary agglomeration of clearance-rack recordings major labels wanted to rid themselves of, and cheap knock-off pop songs of middling to terrible quality.

Pickwick had a small team of in-house songwriters, many of whom used the label to pay the bills, while engaging in more creative pursuits when off the clock. One of these songwriters – in the early/mid-1960s – was Lou Reed.

While Reed churned out dreck for Pickwick during the day, in the evening, he was – to name one notable example – pouring his experiences with deadly narcotics out into a volcanic opus called Heroin.

The Velvet Underground, and the patronage of pop art hero Andy Warhol, were not quite in the cards yet for Reed as he toiled away at Pickwick. Before he left the label, though, Reed was able to sneak one bit of subversive six-string madness into his employer's catalog. Against all odds, a budget label most famous for releasing CBS, RCA, and Disney's leftovers, put out a record in 1965 powered by guitar playing that was daring, radical, and – at least in the context of corporate pop-rock music of its day – unprecedented.

It was called The Ostrich, and was recorded by The Primitives, a band that barely even existed in the real sense.

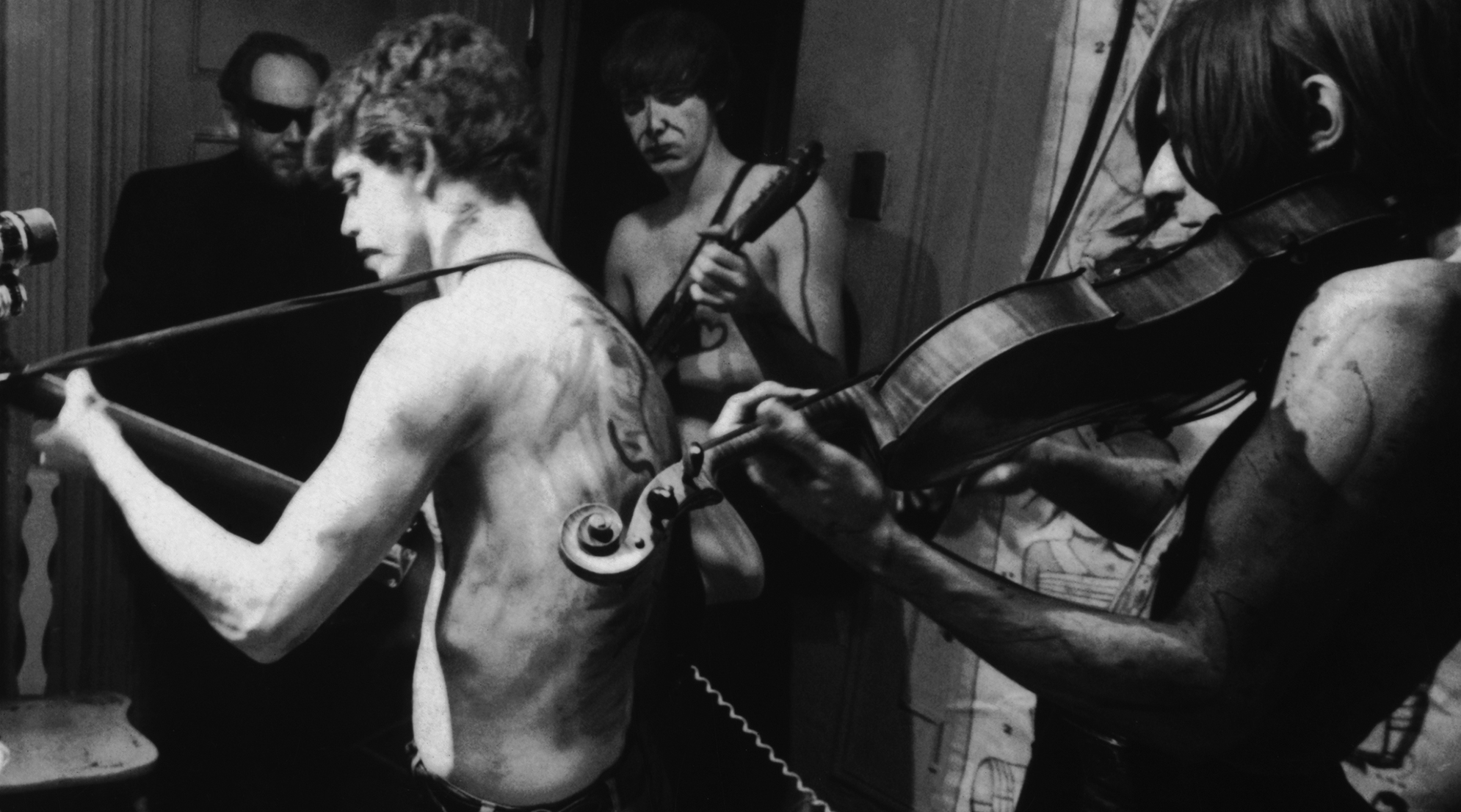

Written by Reed as a parody of dance crazes like The Twist, The Ostrich was recorded by a hastily-assembled bizarro band consisting of Reed plus a trio of serious, avant-garde-minded musicians looking to make a quick buck: Walter De Maria, Tony Conrad, and, on bass guitar, one John Cale.

Cale, in particular, had nothing to do with Pickwick, and – as a classically-trained member of La Monte Young’s ultra-radical Theatre of Eternal Music ensemble – had little regard for pop, folk, or even rock music. There was one thing about The Ostrich, though, that intrigued him. Learning the song, Reed explained to Cale, would be easy, because all of his guitar strings were tuned to a single note.

Of course, alternate tunings were nothing new in folk and blues circles. Drones, in turn, have been a cornerstone of Indian classical music for centuries.

However, in the context of Western beat combo/guitar-rock music – particularly Pickwick's low-quality offerings in the genre – the droning rumble of Reed's guitar in The Ostrich was revolutionary. As a tip of the cap to the song, which became a minor hit, Reed dubbed the tuning – most commonly (but not exclusively) D-D-D-D-D-D – “the Ostrich tuning.“

Though the Primitives' run was ultimately short, Reed and Cale's partnership would endure, and eventually morph into The Velvet Underground.

The ostrich tuning makes two appearances – via Venus in Furs and the Nico-fronted All Tomorrow's Parties – on the band's 1967 full-length debut, The Velvet Underground & Nico. Though the album's commercial impact at the time of its release was negligible, its influence on the development of generations of rock music – from punk to glam, noise-rock, and grunge, is incalculable.

“We focused on trying to inject psychological techniques of hypnosis, drone and repetition into music about topics that we thought were incendiary but within a literary tradition,“ Cale wrote of The Velvet Underground & Nico and its sound in the liner notes of the 50th anniversary edition of the album.

To think that it all started from a goofy parody song released by a bargain bin label.