The Walrus loves books. We love their transportive properties, how you can leave your body and enter their pages, how they dazzle us and expand our minds.

We read dozens of the titles poised to make a splash this fall and have compiled a list of our top ten. It includes dishy and thoughtful nonfiction, expansive and irresistible fiction, gorgeous poetry and graphic novels. This autumn will have no shortage of excellent stories to choose from. We hope this list guides you toward some of the best.

And Then She Fell by Alicia Elliott / Fiction

Penguin Random House Canada

Publication date: September 26

In Alicia Elliott’s first novel, Alice falls down the rabbit hole—hard. A new mother, the wife of a soon-to-be-tenured academic, and a recent transplant to the trendy west end of Toronto, Alice’s successes sour into paranoia. She believes that her screaming baby hates her, that her sunny husband is condescending and callous, and that she’ll never belong in her new community, so utterly unlike the reserve she grew up on. Visions and voices haunt Alice, whose only tether to reality becomes a manuscript she’s poking away at, a modern retelling of the Haudenosaunee creation story. And Then She Fell is at once engrossing and profound, terrifying and empathetic. Like The Bell Jar, it sheds new light on the trope of the mad woman, laying bare the million blows it takes to leave a person unhinged.

—KC Hoard, associate editor

The White Light of Tomorrow by Russell Thornton / Poetry

Harbour Publishing

Publication date: September 2

You can open Russell Thornton’s new collection of poetry, The White Light of Tomorrow, anywhere and find something that throws you back on your heels: “In my memoir I will write about dust,” or how his labourer father’s beard “folded shadow like the metal he had to shear and rivet,” or mist as “mostly emptiness.” Such striking images are part of larger moods: gorgeously embodied feelings of isolation or soaring depictions of emotional debts unmet. If you like your poems quick and hip, The White Light of Tomorrow likely isn’t for you. Nominated for the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2015, Thornton has spent over two decades building a sweeping body of work. He is a spell caster, and in his ninth book, the spells are deeper and stranger than anything he has attempted before.

—Carmine Starnino, interim editor-in-chief

EVE: The Disobedient Future of Birth by Claire Horn / Nonfiction

House of Anansi

Publication date: November 7

Babies born outside of the womb might feel like the stuff of science fiction, but we’re on the precipice of a medical breakthrough, Claire Horn posits in her exploration of ex-vivo uterine environment (EVE) therapy. A legal scholar with Aldous Huxley’s sense of story, Horn imagines this brave (and not-so-distant) new world by charting the history of technological advancements in pregnancy and its attendant inequalities—from the incubator baby show at Coney Island in 1903 to the birth of the first “test tube baby.” Horn wrote the book anticipating that Roe v. Wade would be overturned—and as she found herself unexpectedly expecting—circumstances that imbue her writing with a sense of urgency. In a tale that is equal parts hopeful and foreboding, EVE asks what artificial wombs would mean for a society that continues to compromise the rights of pregnant people.

—Ariella Garmaise, assistant editor

The Mystery Guest by Nita Prose / Fiction

Viking

Publication date: November 28

In her 2022 debut, The Maid, Nita Prose gave us an unlikely sleuth. Molly Gray is slow to grasp things, often misreads people, and is routinely dismissed as “just a maid.” But it is what others discount in her that enables her to solve a mystery that only she can—“through a connection to the human heart in Molly.” The Mystery Guest is a fitting follow-up, with another murder at the Regency Grand hotel—of the renowned writer J. D. Grimthorpe, just as he is about to make an important announcement—that can only be unravelled by the maid who marshals her penchant for noticing “the wrong things at the wrong time.” Molly’s journey back into her childhood reveals more of her relationship with her wise Gran and a particularly heartbreaking scene with her fly-by-night mother. Among the most anticipated thrillers this fall, The Mystery Guest delivers resoundingly on its promise.

—Siddhesh Inamdar, copy editor

River Mumma by Zalika Reid-Benta / Fiction

Penguin Random House Canada

Publication date: August 22

Giller-nominated author Zalika Reid-Benta’s River Mumma follows protagonist Alicia on a high-stakes quest to save the world’s waterways after the titular Jamaican water deity commands her to find a golden comb that’s been stolen. Faced with a deadline only hours away, Alicia traverses Toronto in search of the comb while also dealing with her feelings of failure, given that, at twenty-six, her writing career doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. Amid a crash course in Jamaican folklore, Reid-Benta’s novel takes a gleeful swipe at everything from Toronto’s unreliable transit system to the cult of celebrity (a rapper who may or may not be Drake makes an appearance). But it’s the dialogue—uncontrived, self-aware, and often deeply funny—that drives the story. Even in the suspend-your-disbelief scenes, such as Alicia’s encounters with River Mumma, there are conversations—about priorities, about deadlines—that many of us probably need to be having too.

—Samia Madwar, senior editor

Standing Heavy by GauZ’, translated from French by Frank Wynne / Fiction

Biblioasis

Publication date: October 3

Here is a story of security guarding in Paris, told in two narratives: one conventional, following three men from Cote d’Ivoire who patrol the flour mills (even after they’re decommissioned) on the left bank of the Seine, the other a series of rapid-fire observations from the eyes of unnamed guards on duty at places such as Sephora on the Champs-Élysées. The book’s longer passages track decades of social change in France, revealing the impact of shifting attitudes toward immigrants, while the shorter and often hilarious sections span a single day of standing still in one place, watching customers try on lipstick or be spritzed with Givenchy. It’s a spry volume of 167 pages—first published in French in 2014 and shortlisted for the International Booker Prize this year—that manages to trade heavily in politics while also sneaking up on your sympathy. I won’t spoil the end, but it startled me in its poignancy.

—Dafna Izenberg, features editor

Valid: Dystopian Autofiction by Chris Bergeron, translated from French by Natalia Hero / Fiction

House of Anansi

Publication date: November 7

In the year 2050, a monstrous AI named David runs Montreal with an iron fist. He has outlawed anything he can’t understand, including identifying as something other than the sex one was assigned at birth. This has had catastrophic consequences for Christelle, the trans woman who helped create him. In Chris Bergeron’s Valid, a seventy-year-old Christelle, who has been forced to live as a man for decades, immobilizes David for a few hours so she can commit a most revolutionary act: telling her true story. The narrative unfolds as a monologue, delivered by Christelle to David, who occasionally interrupts her soliloquy with digitized rebuttals. Bergeron, who weaves her own life story into Christelle’s, has crafted a masterful, complicated work of autofiction, one that will leave readers convinced that a potent weapon against dogma and autocracy is a life lived authentically.

—KC Hoard, associate editor

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein / Nonfiction

Knopf Canada

Publication date: September 12

Naomi Klein’s book—part memoir, part cultural analysis—is an unsettling ride through our doublings online. She examines how big companies are making bank, harvesting our data while we splinter ourselves, becoming increasingly fractious and distracted. That alone would make for an interesting read. But the real hook is Klein’s look inward. The public figure who brought us No Logo interrogates not only her own personal brand but her disintegrating sense of self as she grapples with public confusion over her namefellow with pretty much polar-opposite political beliefs: Naomi Wolf.

—Monika Warzecha, digital editor

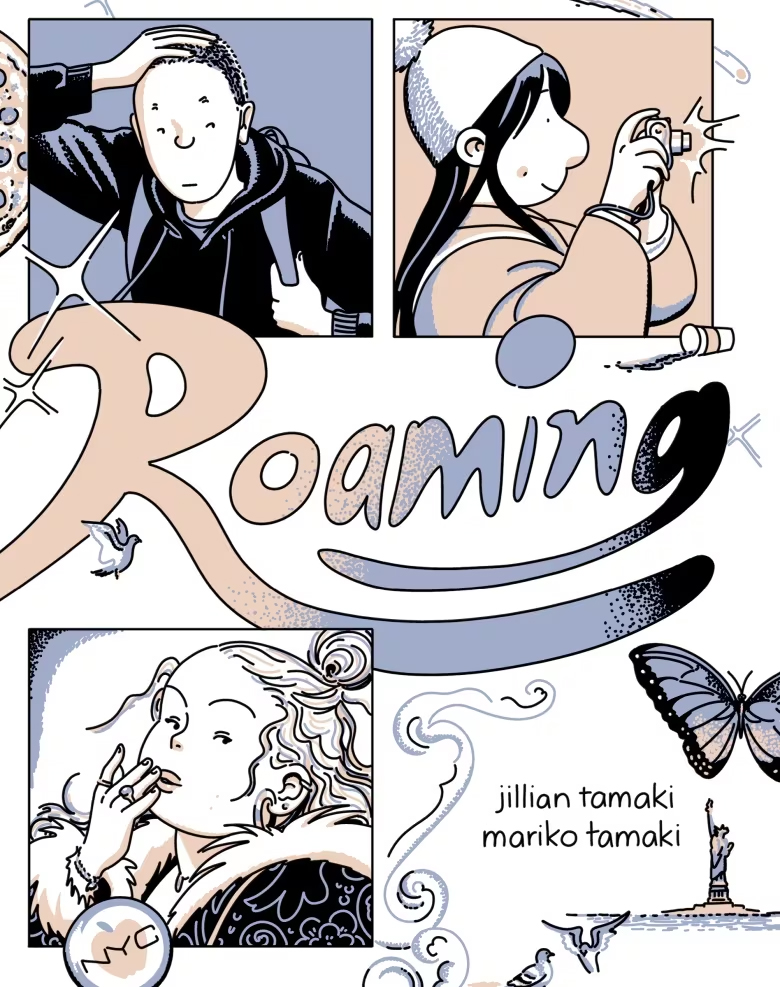

Roaming by Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki / Graphic novel

Drawn & Quarterly

Publication date: September 12

Roaming, a graphic novel about three friends (some closer than others) taking a spring break trip to New York City in 2009, does an excellent job of showing the city through the eyes of tourists. The illustrations playfully capture the grand scale of a place where you can’t help but look up, each chapter marking a day of the trip and the group trekking to another landmark. But, somehow, travelling with friends never goes as smoothly as you imagine it will. The story deftly shows how the dynamics of relationships change on the cusp of adulthood, acting as a snapshot of that particular time in life (especially if you’re old enough to have used a digital camera instead of a phone on vacation). Read and experience the thrill of a crush, the pain of being a third wheel, the joy of being inside the M&M’s store.

—Meredith Holigroski, senior designer

The Fraud by Zadie Smith / Fiction

Hamish Hamilton

Publication date: September 5

Zadie Smith’s sixth novel is a many-headed hydra. It’s a work of historical fiction, set between nineteenth-century England and pre-Emancipation Jamaica. It’s a biting comedy of manners, starring an abolitionist housekeeper who skewers the pretensions and hypocrisies of her declining novelist cousin’s literary circles. It’s a courtroom drama that follows the real-life Tichborne Trial, in which “the Claimant” insisted he was the rightful heir to a fortune. But who is the titular Fraud? Is it Eliza Touchet’s pompous employer, whose hack-job books have fallen out of vogue? Is it the Claimant, who might be a low-class butcher? Or the ex-slave from Jamaica who testifies to the opposite? Or is it England itself, whose “civilized” empire rests on a decidedly uncivilized history? The Fraud is an intricate tapestry of Victorian life, braided with sex, money, and snobbery, aristocratic judges and bourgeois juries, plantations called Hope, false identities, false relationships, false histories. Smith is at her full power.

—Connor Garel, the Justice Fund writer in residence