One by one, members of Connecticut men’s basketball royalty made their way out of the stands and up onto the court at NRG Stadium. Here came Kemba Walker, then Ray Allen, then Emeka Okafor, then Rudy Gay. Walking on a bed of confetti that had just dropped from the ceiling, the program’s history had come to pay its respects to the present.

There was Allen, offering words of congratulations to guard Jordan Hawkins, then shadowboxing with coach Dan Hurley. There were Okafor and Gay, wrapping their arms around Hurley. And there was Walker, with a spectacularly gaudy Huskies pendant around his neck, declaring the program’s elite position in the college basketball hierarchy.

“[Jim] Calhoun started it. Hurley ended it,” Walker says. “And we’re about to keep going.”

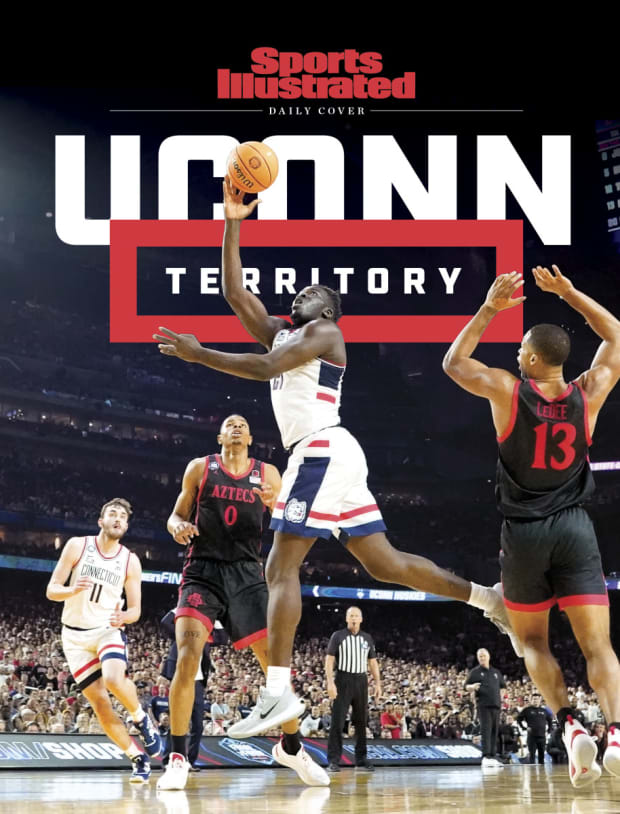

In subduing the determined San Diego State, 76–59, on Monday, the championship lineage continues. With a fifth national title under a third coach since 1999, UConn’s utter rampage through the bracket in this NCAA tournament firms up blueblood status. The Huskies separated themselves from the pack this postseason, winning six games by lopsided margins and, in the process, have separated themselves from any other program in the past quarter century.

Robert Deutsch/USA TODAY Sports

Don’t look back, traditional powers. The boys from Storrs are gaining on you. In fact, they’ve overtaken a few of you.

UConn’s five titles in the previous 25 years are two more than North Carolina’s and Duke’s in that span, three more than Kansas’s and Kentucky’s, five more than UCLA’s and Indiana’s. Its six Final Fours from 1998 onward are topped by only the Tar Heels’ eight.

The only schools with more all-time titles than UConn are UCLA (11), Kentucky (eight) and North Carolina (six). Only four schools have won titles with three or more coaches: Kentucky with five, and North Carolina, Kansas and now UConn with three. Calhoun gave birth to the thing, but thanks to Kevin Ollie (2014 title) and now Hurley, the Huskies have more than a one-coach body of work.

College sports can be weirdly resistant to rising programs that challenge tradition, but there is no way to ignore or minimize what the Huskies have done. The list of Cadillac programs in the history of the sport must include UConn.

“We’ve got too much rich history,” Walker says. “There’s no doubt. We’ve got five. Three different coaches. Same program.”

Says Allen: “You talk about the most traditional programs, the ebbs and flows, the highs and lows, we’ve still managed to come out of that and put teams on the floor that can win championships.”

And as Walker alluded to, Hurley’s run might just be getting started. The coach is only 50 years old, and as a native Northeasterner he’s in his geographic and psychological comfort zone. This crushing tournament run could be the start of something big.

UConn won every tournament game by at least 13 points, the first men’s national champion to do that since Indiana in 1981 (when the Hoosiers had to win only five games). The Huskies’ average margin of victory was 20 points, the highest for a champion since Kentucky’s ’96 team averaged 21.5. True, the Huskies never played anyone seeded better than No. 3, but they waylaid everyone who came in their path.

Brett Wilhelm/NCAA Photos/Getty Images

“We knew we were the best team going into this tournament,” Hurley says.

That belief was born early, when an unranked UConn team stormed through the nonconference schedule with an 11–0 record. The Huskies pushed their undefeated start to 14–0 before wobbling for about a month, then regrouping for February and March. (The Walker-led 2011 national champs also went undefeated in nonconference play, also struggled in league play and also won it all in Houston.)

“I knew we were going to win the national championship in December,” Hawkins says.

But that UConn-fidence came with some acute Big Dance pressure. The Huskies had been bounced in the first round of the previous two tournaments, upset last year as a No. 5 seed by No. 12 New Mexico State and in 2021 as a No. 7 seed by No. 10 Maryland. A deep tourney run has to start with a first-round win. And when the bracket came out with UConn as a No. 4 seed matched up with March warlock Rick Pitino and Iona, that upped the anxiety.

“Me and [assistant coaches] Kimani [Young] and Luke [Murray] kept saying, the most pressure-packed game that we’ll ever coach in or play in was going to be that first-round game,” Hurley says. “We didn’t know who it was going to be. And obviously it was Iona, and then hysteria started. We were playing the bogeyman, Rick Pitino, and that we were in big trouble. We knew we couldn’t go out like suckers again in the first weekend. We also didn’t wear that around the players, but we certainly felt it.”

When Iona led 39–37 at halftime, the pressure was palpable. But from that point on, UConn became an absolute threshing machine. The Huskies held Iona to 24 second-half points, then similarly dismantled Saint Mary’s in the second half in the round of 32. They shot Arkansas out of the gym immediately in the Sweet 16, blew out Gonzaga in the second half, easily controlled Miami in the national semifinals and then largely had their way with San Diego State.

The Aztecs uncharacteristically hit a few shots early Monday to take a 10–6 lead but were completely shut down by a UConn defense that held both Gonzaga and Miami to season-low points totals. As the San Diego State assault on the rims wore on, the Huskies locked in offensively. When guard Andre Jackson Jr. dropped a between-the-legs assist behind him to trailing guard Joey Calcaterra for a transition three-pointer, UConn led 36–20 and it appeared school was out.

But San Diego State didn’t make its first national title game by folding when things were going poorly. The team that came back from 14 down against Florida Atlantic, nine down against Alabama and eight down against Creighton cobbled together enough baskets in the second half to cut the deficit to five with a little more than five minutes to play.

Carmen Mandato/Getty Images

With the SDSU fans roaring, UConn came down and ran a play for Hawkins off a curl for a three-pointer at the top of the key. He caught and rose in one fluid motion, flicking the shot artistically into the air and through the net. That was all she wrote.

UConn pushed out to a comfortable enough lead to bring in the subs for the final 30 seconds, including Hurley’s son, Andrew. Grandfather Bob Hurley Sr., patriarch of a great Jersey City basketball family, noted with pride afterward that Andrew and the other walk-ons got to play in every tournament game, a reflection of UConn’s dominance.

Andrew Hurley ended the game by jubilantly spiking the ball at midcourt when the clock ran out. Sensing an opportunity, UConn big man Adama Sanogo ran in from the bench area to grab the ball, tucking it under his arm and not letting it go for quite a while. The Final Four’s Most Outstanding Player could justifiably lay claim to the game ball.

Sanogo, Hawkins and Jackson formed the nucleus of this team, all NBA-level talents who likely will declare for the draft in the coming days. Sanogo’s year-over-year growth is what elevated this UConn team from promising to powerful. The 6'9", 245-pounder was a matchup problem for every opponent in this tournament.

The native of Mali navigated through this run while also fasting from sun-up to sundown in observance of the Islamic month of Ramadan. He had to work his schedule around early wakeups to eat and then late feedings before games.

“He was up super early today, loaded up,” Bob Hurley Sr. says. “He had his peanut butter and jelly tonight at sundown, got his fluids in, and was ready to go.”

Sanogo was one of the key recruiting victories Dan Hurley and his staff pulled off in building their lineup. Sanogo was at The Patrick School in New Jersey and close to a decision in the early months of the pandemic, and the UConn staff was veering from confident to concerned that they might lose out in the end. Hurley and assistant Young mounted a late Zoom call offensive to make sure they got their four-star big man in May 2020.

Three months later, a similar Zoom recruitment swayed 2021 four-star Hawkins to commit to the Huskies. Hurley was selling a UConn return to glory to anyone who would listen. “He said we had a chance to do something special here, and we did,” Hawkins says. “Absolutely amazing.”

Between celebratory moments on the court, Hurley was trying to get himself out of Coach Mode. Apropos for his personality, Hurley was only partially successful at enjoying the moment.

Robert Deutsch/USA TODAY Sports

“I’m still thinking about some things, that typical Dan Hurley fashion, the amount of missed layups,” Hurley says. “Jordan’s [missed] dunk to start [the second half], we should have been up 18, 20 at halftime. That’s just really the way my mind works. I think when I get back to the hotel and I just get in a room for a little bit, I'll be able to kind of decompress a little bit.

“I’m just mostly proud of the way we’ve done it and with the type of people that we’ve done it, the way we recruit young players, develop young players. We do it without cheating. We do it without lying.”

With this title, Hurley added to two legacies: UConn’s and his family’s. Bob Sr. is one of the all-time greats in high school coaching history, and Bob Jr. won two national titles as a star point guard at Duke and is the current coach at Arizona State. (The brothers embraced on the court postgame, with Bobby declaring the night, “one of the top sports experiences I’ve had.”)

This, now, is Dan’s championship moment. Perhaps the first of many. The sideline wild man can coach with the best of them.

“Obviously there’s a certain level of validation that’s going to come from this,” Dan Hurley says. “But I just feel like my career in coaching, even prior to this—maybe I don’t do a great job kissing the media’s ass and presenting this image that’s incredibly likable, but I am who I am. I’m from Jersey City, and this is how people from Jersey City act.”

The Jersey City kid said that in the postgame press conference with his national championship hat spun around backward on his head, the word “CHAMPIONS” facing the world. When the press conference ended, Hurley grabbed the placard with his name on it and said, “I’m taking this.” He then grabbed the placards left behind by his players.

They’ve earned their title mementos. And Connecticut men’s basketball has earned its prominent place on the very short list of the blueblood programs in the sport.