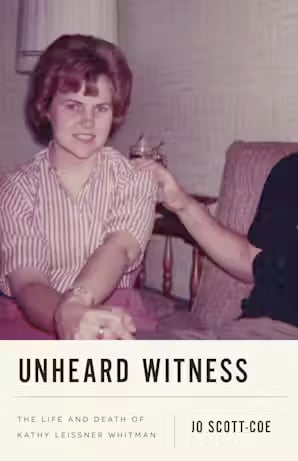

An unusual new book dives deeply into the mind of an all-but-forgotten victim of the University of Texas Tower Shooting: the sniper’s wife, Kathy Leissner Whitman. Told in vivid detail through an enormous trove of letters that Leissner’s brother kept long after her violent death, the reader plunges immediately, uncomfortably, and intimately into the life and thoughts of a doomed woman. They see that woman in love, browbeaten and abused, and finally, stabbed to death by her husband in the pages of Unheard Witness: The Life and Death of Kathy Leissner Whitman, out this month from (appropriately) the University of Texas Press.

We know from the beginning that Kathy, the charming Central Texas protagonist and, through her letters, the narrator, will die terribly at the hands of her husband, Charles Whitman, in a massacre still remembered as the first mass shooting in modern U.S. history. But that doesn’t leave the reader any less compelled to want to scream, “Get away now!” at this well-coiffed and intelligent young woman. The daughter of a successful farmer and a teacher, Kathy dutifully stands by her man as he roams from the University of Texas at Austin to Florida, a Marine base in North Carolina, and finally back to UT, where she’s among the first to die in 1966 when Charles fully loses control of the erratic, abusive, and violent impulses that surface in staccato bursts throughout the book.

Author Jo Scott-Coe begins with the love story of how Charles, a good-looking, muscular Marine, woos and wins Kathy in their UT student days, during which Charles presents her with a “bespoke tag pendant” signifying they’re officially “dropped” (the 1960s parlance for promised) on February 12, 1962. The author then shares increasingly disturbing narratives that reveal how Charles deeply disappoints his loving wife and himself by flunking out of school and getting kicked out of the U.S. Marine Corps, all while keeping his more stable and successful spouse’s desires and wishes on a tight leash.

Scott-Coe sketches gripping episodes tied to intimate letters originally intended to remain between a young married couple that illustrate how completely Charles controls Kathy—remarkable even for the 1960s, an era when many American men dictated how their wives would be addressed (in this case, as Mrs. Charles Whitman), what they wore, and what jobs they could hold. At one point, Kathy writes this response to one of her husband’s angry episodes: “I want to know your every whim all over again and I’m afraid I’ve forgotten some of them. Will you help me learn to be a good lover?” His responses: “I got your letter and it sure made me feel all my angry [sic]was worthwhile” and “I can’t wait to make you pregnant—very much pregnant.”

Affection and tension alternate throughout the narrative, which serves as a gripping reminder of the larger issue of how many domestic violence victims suffer from subtler kinds of emotional abuse and hyper-control for years before being physically targeted or killed. Indeed, many Texans are killed by partners (or by exes) only after they attempt to escape, as regular reports compiled by the Texas Council on Family Violence show. This book also illustrates in troubling detail just how hard it is for outsiders, even loving parents and siblings, to fully understand or intervene when domestic bliss veers into domestic violence. At one point, Kathy’s loving mother attempts to intervene, writing her son-in-law: “I am in no way suggesting that you need to go to a psychiatrist—for believe me if I did believe it I would say so quite frankly. I do feel that both of you together and separately should go to a marriage counselor as soon as possible.”

And Kathy lived in the 1960s America, a time when the government barred escape routes from domestic abuse by preventing women from having bank accounts, lines of credit, or owning their own property.

Scott-Coe, an English professor, wrote this book after writing essays about other women whose murders seemed to have been eclipsed by well-known crimes, including one article she titled, ”Invisible Women, Fairy Tale Deaths: How Stoires of Public Murder Minimize Terror at Home.”

There’s even a modicum of sympathy shown toward Charles, whose macho behavior veers into misogyny and accelerating abuse. The author, relying on correspondence, shares how Kathy and Charles witness and react to the verbal abuse that Whitman’s father dishes out to his family in Florida. ”His father, C.A. Whitman, was a working patriarch who built a successful plumbing and septic cleaning business but shamelessly terrorized Charles and his two younger brothers. … As well as their mother.” She also relates how Charles tries to help his apparently gay (but closeted) younger brother and later brings his mother to Texas in a doomed effort to protect her.

But Scott-Coe does not delve more deeply into the causes of Whitman’s final horrifying transformation into the UT Tower terrorist, which he begins by shooting his mother and then fatally stabbing Kathy—the woman who’d stuck with him, just as her vows had said, for better or for worse.

Jo Scott-Coe chooses to bring back to vivid life Kathy Leissner Whitman, the UT Bell Tower shooters’ victim who’s so often forgotten in other narratives about the mass shooting that claimed 14 other lives.

The author’s narrow focus seems fully justified by her own title: Unheard Witness: The Life and Death of Kathy Leissner Whitman. She chooses to bring back to vivid life Kathy, the UT Bell Tower shooters’ victim who’s so often forgotten in other narratives about the mass shooting that claimed 14 other lives on campus after Charles ascended with his arsenal into the tower. And Scott-Coe succeeds: This book is an intimate and uncomfortable read that puts the reader deep inside Kathy’s mind.

However, readers who know the rest of the University of Texas Tower Shooting story will recall that Charles was not only a troubled young man and an abusive husband, but also suffered from an undiagnosed brain tumor. Whitman’s own suicide note reflected his confusion: ”I do not really understand myself these days. I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I cannot recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts… ”

This otherwise wonderful book suffers a bit from the omission of that tumor, which was missed during Charles ’s life despite visits to a Texas psychiatrist and his physicals as U.S. Marine. If it had been detected, his life and his wife’s would likely have had a very different ending.