In The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire, Washington D.C.-based investigative journalist Tim Schwab examines Bill Gates as a case study of how billionaire philanthropy can parlay extreme wealth into political influence sans accountability. In an email interview with The Hindu, Schwab talks about his new book, the dangers of unconstrained philanthropic power, and where India figures in Gates’s scheme of things. Edited excerpts:

How difficult was it to research and/or publish journalistic critiques of the Gates Foundation’s philanthropic work?

My reporting examines the Gates Foundation as an unregulated political organisation. I’m showing how Bill Gates meets with elected leaders around the world, shaping government priorities and spending on everything from public health to public education. This isn’t charity but rather undemocratic political influence. Most mainstream news outlets, by contrast, have tended to report on the good deeds of the Gates Foundation, profiling its big donations and ambitious goals. So, it has not been easy to get critical reporting on Gates published.

Has it gotten less or more difficult over time?

I do think it is getting easier. Following Bill Gates’s divorce in 2021, the news media widely covered the allegations he faces of misconduct toward female employees (which Gates denies). Around this same time, Gates also was widely criticised by public health experts for his controversial leadership role in the pandemic response, which many saw as too closely aligned with Big Pharma. I think these recent events made more journalists and editors understand that the story of the Gates Foundation is far more complex than they realised. To be sure, the contradictions in the prevailing news coverage are stunning. While journalists have endlessly profiled how Bill Gates is giving away all of his money, for example, the reality is he has managed to become phenomenally richer during his tenure as a philanthropist. In the years ahead, I think journalists will profile Gates less as the saintly humanitarian and more as the emperor with no clothes.

Today a person with no public health background is arguably the most influential voice in global public health. Is this a cause for alarm, or is it a happy coincidence, given the millions of lives he’s reportedly saved?

If you try to track down the evidence surrounding the millions of lives Gates is saving, you end up finding research that the foundation itself funded. This research, which is not independent, is telling you one side of the story. It’s not telling us how many lives were lost because of Gates’s wrong-headed strategies, or how many more lives we could have saved if we took a different approach. During the pandemic, for example, there were widespread calls, led by India and South Africa, to waive patents over COVID vaccines. Gates used his celebrity and bully pulpit to challenge these calls, arguing that his foundation’s charitable partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry made a patent waiver unnecessary. But Gates’s charitable promise to deliver vaccine equity failed. What we saw instead was vaccine apartheid, as the poorest people on earth went to the back of the queue. Not surprisingly, there is no billionaire philanthropist funding research into how many lives were lost through Gates’s failed response effort.

To your question, it is true that Bill Gates is a college drop-out who has no formal training in most of the areas in which he works, whether it’s pandemics or climate change or agriculture. His influence in world affairs only really makes sense if you believe that the richest guy deserves the loudest voice.

How would you describe Gates’ working style at the Gates Foundation?

The same features that animated Gates’s work at Microsoft also energise his work at his foundation. For example, Microsoft, under Gates’s leadership, had a reputation for being a bully and a monopoly. The same critique has long hounded the Gates Foundation, which is seen as using its money and influence to bully its priorities into public policy. As one example, 15 years ago, the head of the WHO’s malaria programme warned that the foundation’s bullying influence over malaria research was distorting the field and “could have implicitly dangerous consequences on the policy-making process in world health.”

If there is a through line in Gates’s career, it is his hubris, his belief that he is right and righteous in everything he does, and that his great wealth entitles him to take power — whether it is trying to control the computer revolution through Microsoft or to organise how we feed, educate and medicate our children through his philanthropic work.

Where does India figure in Bill Gates’s scheme of things?

Twenty years ago, at the beginning of his philanthropic career, Gates made India a central focus of his foundation, just as he had made India a major focus of Microsoft. The Gates Foundation’s first foreign office was in Delhi, and, when I was researching my book, I found that India is the largest destination of Gates Foundation funding — outside of the U.S. and Europe.

One feature that makes India so important to the foundation is its role as the so-called pharmacy of the world. Gates has sought out partnerships with Indian pharma to try to move low-cost drugs and vaccines into the poorest nations on Earth. Much of Gates’s work in the pandemic, for example, hinged on a deal with the Serum Institute of India to produce vaccines for African nations. As a major wave of infections spread across India in early 2021, the government effectively issued an export ban, directing Serum’s shots into the arms of Indian citizens. That political decision was one reason Gates’s Covid response effort failed. But this episode also helps show how many of Gates’s philanthropic projects — globally — depend on Indian corridors of power, whether it is the private sector or the Modi administration.

How would you contextualise Gates’s decision to give the prestigious Global Goalkeeper Award to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2019?

Gates gave the humanitarian award at a time when Modi’s administration was in the midst of an international PR crisis, facing widespread reports of human rights abuses in Kashmir. Though the news media doesn’t often raise criticism around the foundation, many outlets did with this episode. One foundation employee based in India even publicly resigned in The New York Times, asserting that the award to Modi was at odds with the foundation’s humanitarian mission.

So it was a big PR blunder for the foundation on the world stage, but I think it was also a political calculation by Gates. In all the work the foundation does around the globe, it has to work closely with governments. The foundation needs political allies because the work it is doing, essentially, is political in nature, trying to influence public policy at the highest levels. If you follow the news, you’ll see that Bill Gates is constantly meeting with elected leaders, all over the world, trying to build political support for his agenda. I think this helps explain Gates’s public displays of affection to Modi, which are becoming increasingly bizarre, like the four-hour-long promotional video last month.

Your book dwells on the Gates Foundation’s interventions in India with respect to HIV prevention and HPV vaccines through the so-called ‘technical support units (TSUs)’. What did the TSUs do for India?

Some sources I spoke to in India describe these TSUs as a kind of parallel public health system, carrying out work that normally is managed by governments. That said, Gates operates in India according to formal agreements with government partners. So, arguably, the Indian state has institutionalised Gates’s role in public health. I’ve spoken to many sources who have worked directly with the foundation in India who see Gates’s influence as wholly inappropriate and often counterproductive. You can also see this sentiment all over social media. The basic, democratic question being asked is: why is an unelected billionaire from Seattle playing such a large role in India’s public health?

In your assessment, which are the top surrogates of the Gates Foundation that carry out its agenda — in India, and globally?

The foundation has donated more than $1.5 billion to organisations based in India. However, even larger sums of money may flow into the country via organisations based outside of India. In the foundation’s sprawling work to improve public health in Uttar Pradesh, for example, it works through the Canada-based University of Manitoba. In its work in Bihar, Gates directs its charitable dollars to the group CARE, whose home office is in the U.S.

The largest single recipient of Gates’s funding globally is a group named Gavi, which aims to expand vaccinations in poor nations. Gavi, which has received $6 billion from Gates, is not located in a poor nation. It’s based in Switzerland. Over the life of the Gates Foundation, nearly 90% of its charitable dollars have gone to rich nations, not the poor nations it claims to help. It’s a fundamentally colonial model — funding the rich to help the poor — and it hasn’t been particularly effective.

Philanthropic organisations are not supposed to engage in lobbying. Yet Bill Gates wields tremendous influence over policy-making.

This is part of what makes billionaire philanthropy so dangerous — it is difficult to recognise it for what it really is: political power. Just as billionaires use lobbying or campaign contributions to try to influence public policies, they can also use philanthropy. At the very least, we should subject the Gates Foundation to new accountability and transparency rules. We should scrutinise and regulate the foundation’s charitable donations as money in politics.

You write, “While critics often present the Gates Foundation as allied too closely with business interests... the foundation itself is actually a competitor in the marketplace — it IS Big Pharma.” How can a philanthropic body be a market competitor?

With diseases that mostly affect poor nations, like malaria or TB, there isn’t a profit motive for Big Pharma to develop new medicines. So you see the foundation stepping in and acting almost like a pharmaceutical company — donating money to private companies, taking investment stakes in companies, helping launch new companies, or sitting on boards of directors. In some cases, the foundation creates financial ties to multiple competing companies, allowing it to have influence over an entire field. Some pharma developers I interviewed who have worked with the foundation describe it as abusing its market power and even stifling innovation — criticisms that are uncannily similar to those raised against Microsoft 25 years ago.

To what extent is the Gates Foundation’s pro-GMO (genetically modified organisms) stance shaping research agendas in this domain?

Bill Gates has long been one of the world’s most vocal promoters of GMOs, promising that the technology would deliver game-changing yield increases and life-saving nutritionally enhanced crops. The technology has not delivered, however, and most nations around the world have decided GMOs are not worth the costs — either the financial costs of the technology or the potential costs to the environment. The GMO story really speaks to Gates’s dogmatic belief that technological solutions are always the best interventions.

Gates’s tech-driven agricultural development plan — branded as the new ‘green revolution’ — today faces widespread opposition from farmer organisations across the African continent who see the foundation as doing more harm than good. The Gates Foundation has largely refused to engage with criticism from its intended beneficiaries, however, taking the colonial attitude that it knows what is best for the global poor, that beggars can’t be choosers.

You point out that the Gates Foundation has donated more than $12 billion to universities and helped underwrite more than 30,000 scientific articles. Why is that a concern — isn’t funding science a good thing to do, and how does it matter, given that funding disclosures are now routine?

It’s important to think about the Gates Foundation as a political actor. It is not donating money as much as it is buying influence. It has its own narrow ideas about how to remake public policy. One tool it uses to advance its ideas is funding advocacy groups and think tanks. Another tool is meeting directly with government leaders. Another tool is funding journalism. Another tool is funding research.

I’ve interviewed many scientists who say the foundation micromanages the research it funds: dictating which data are used, how the data are presented, which questions are asked and which questions aren’t asked. Academics have also coined a term — ‘the Bill chill’ — to describe the reluctance that researchers have to bite the hand that feeds them, to publish something critical about their patron. So, the criticism is that Gates’s funding of research can compromise the independence and integrity of science, distort science-based policymaking, and also stifle public debate about the foundation itself.

Do you think Gates’s philanthropy ought to pivot away from ‘silver bullet’ approaches such as vaccines, and aim its interventions toward building public health infrastructure, especially in poorer countries?

The kind of work you’re describing — public health in poor nations — is, in my view, the job of the state. Public policy should be organised in a public, democratic process. We should not allow billionaires — no matter their nationality, no matter how well meaning — to buy a seat at the democratic decision-making table, even if they present themselves as well meaning philanthropists. Instead of asking how Gates should spend his money, I think we should ask a different set of questions: Why does Gates have so much money? Why have we — all of us — made the political decision to organise our economy in such a manner to allow one man to control a $130 billion private fortune, as Gates currently does, while so many people on earth can’t afford basic necessities? And what is stopping us from making different political decisions? To me, the real debate is less about how to try to make the Gates Foundation kinder or gentler or less harmful, but rather how do we reorganise society and reimagine our economy so that we don’t allow people to become this grotesquely wealthy in the first place. My book focuses on Bill Gates and the Gates Foundation, but it’s really a case study for the larger problem of extreme wealth and how it threatens democracy.

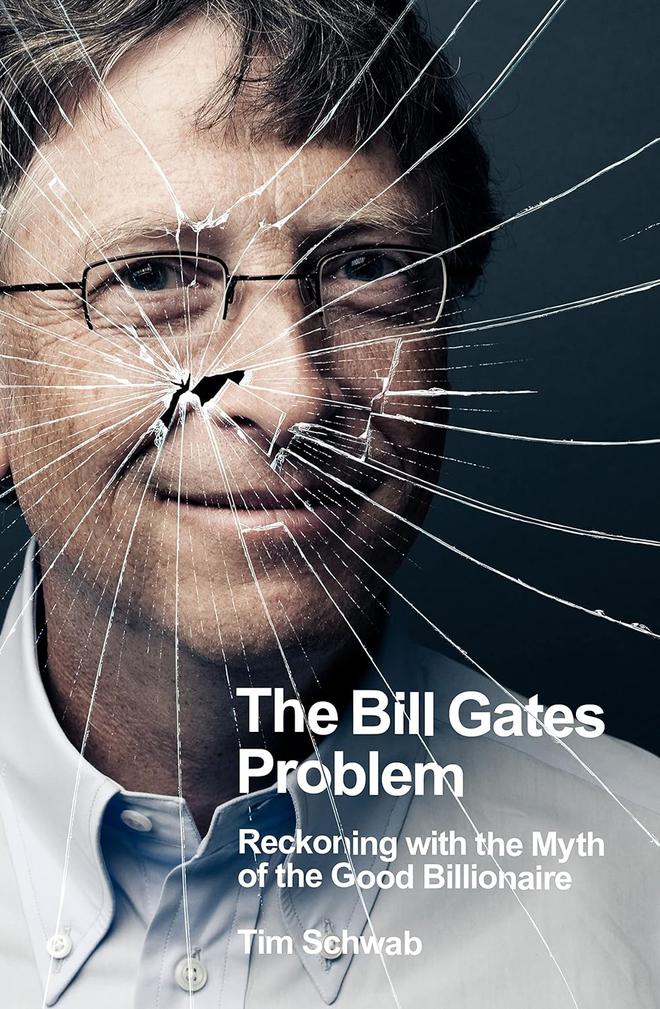

The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire; Tim Schwab, Penguin Business, ₹799.

Read the full interview at www.thehindu.co.in