The Arctic tundra, a critical “carbon sink” for thousands of years, is now releasing more of the greenhouse gas than it takes in, scientists have announced.

Carbon sinks like the Arctic play crucial roles in regulating the planet’s climate. The region also functions as a heat sink for the planet, losing more heat to space than it absorbs from the sun’s rays and balancing out heat intake in lower latitudes.

Sea ice there acts like the planet’s air conditioner. But, it is also one of the fastest-warming places in the world. Scientists say that the rapid warming is due to human-caused climate change.

“The Arctic is warming up to four times the global rate, and we need accurate, holistic, and comprehensive knowledge of how climate changes will affect the amount of carbon the Arctic is taking up and storing, and how much it’s releasing back into the atmosphere, in order to effectively address this crisis,” Dr. Sue Natali, Woodwell Climate scientist and lead author of the research, said in a Tuesday statement.

The work was published then in a chapter of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s 2024 Arctic Report Card.

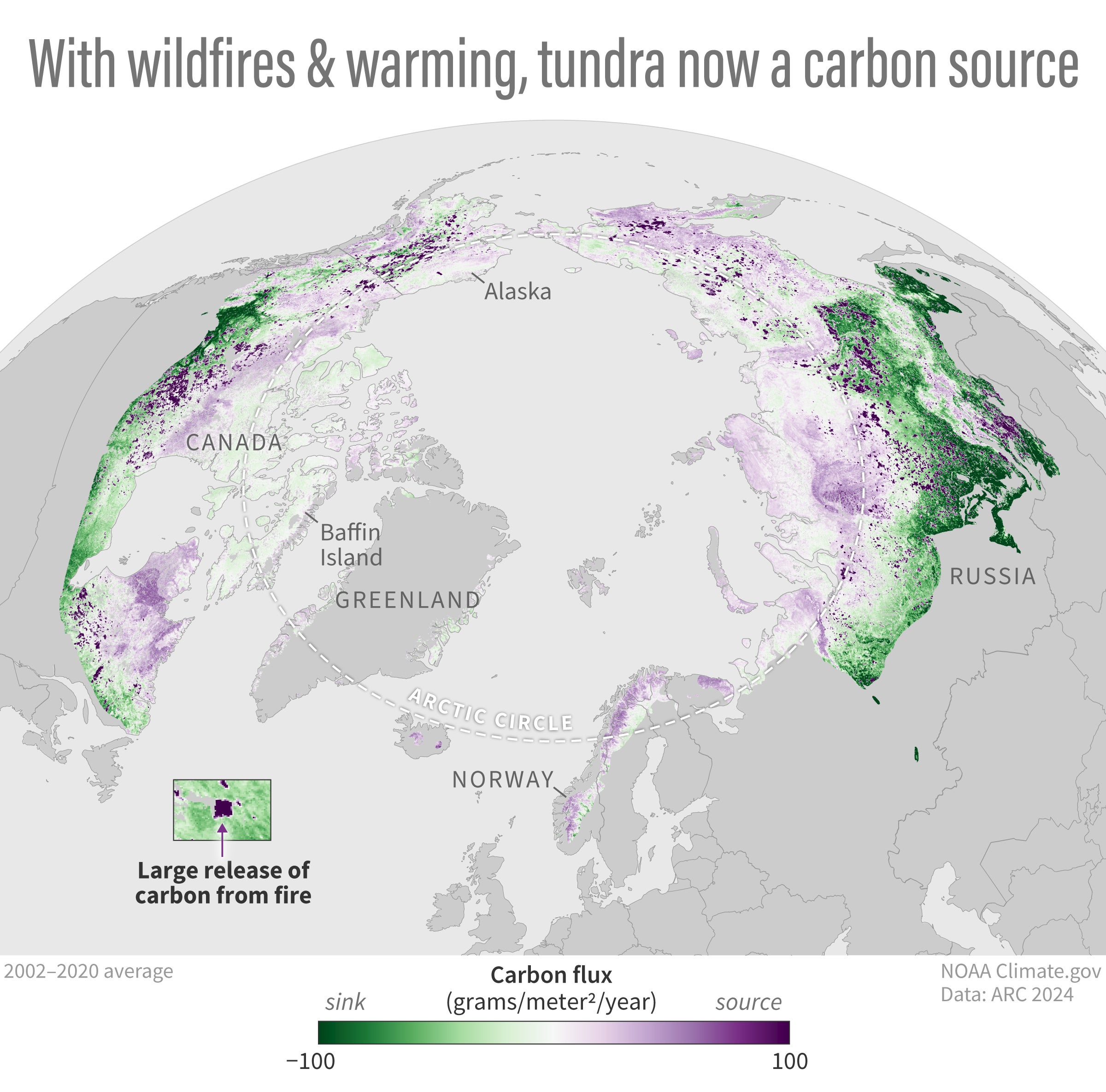

Researchers found that rapid Arctic warming driven by rising surface air temperatures is resulting in a range of ecosystem changes that are leading to increased emissions in the region, including wildfires, plant and microbial changes, and thawing permafrost. Permafrost is ground that is permanently frozen, which is common in places near the North and South Poles.

They used on-the-ground carbon dioxide and methane data, coupled with remoting sensing and climate data and machine learning techniques.

“Essentially, the further north you go when you get into colder areas and what we call continuous permafrost and the vegetation starts getting sparser, the more carbon we’re seeing being emitted,” Dr. Brendan Rogers, an associate scientist at the Massachusetts-based Woodewell Climate Research Center who was a co-author of the research, told The Independent on Wednesday.

“It’s of concern in the sense that, for thousands of years, these systems have acted as a long-term average carbon sink,” he added.

The changes, Dr. Ted Schuur — another author and professor of ecosystem ecology at Northern Arizona University — noted, can be seen firsthand. He spends summers in Alaska.

“You can see it and it’s just changing around you. And, I’ve been doing this long enough, like a couple of decades, where I know that it’s happening and can see it. And, I think, scientifically, what you’re always asking yourself is, ‘OK yes, I’m seeing something, but is what I’m seeing different from how it would used to be historically?” he explained. He said the Arctic Report Card separates the experience and shows scientifically that it’s a real change.

Dr. Jacqueline Hung, a research scientist at Woodwell and co-author, operates two data sites out of southwestern Alaska.

“A lot of these changes are very dramatic to the landscape and also irreversible,” she said. “So, understanding that what’s happening in Alaska right now will have longer term and larger scale effects on what’s happening around the planet.”

In addition to likely being the warmest year on record, this year marked the second-warmest average annual permafrost temperatures on record for Alaska and it was the second-highest year for wildfire emissions north of the Arctic Circle, the scientists reported.

The tundra region remains a source of methane and the boreal forest region is still a carbon sink.

The carbon emissions from the region, Rogers said, would probably be significant.

“They definitely are higher with higher levels of warming and they’re lower with lower levels of warming. So, that is a good thing in the sense that if we pursue aggressive emissions reductions we can have a much better chance at dealing with the emissions coming out of permafrost,” he said. “And, they’re significant, but they’re not going to dwarf fossil fuel emissions. That’s still the main problem and the main thing to focus on.”

“We’ve done some other estimates that say that the Arctic could be emitting carbon over this next century [at] the same size as an industrialized nation might be doing,” Schurr said.

The findings come after scientists warned that the Arctic could see its first “ice-free day” in the coming decades, and amid widespread concern about Earth’s carbon sinks. Research published over the summer found that forests and other land ecosystems failed to curb climate change last year.

The Amazon rainforest’s role as a critical carbon sink is also under threat, and a recent study published in the journal PNAS found just 25 percent of the world’s surviving tropical rainforests are in good condition.

Rogers said these findings should be motivation to pursue aggressive emissions reductions.

“The best time to do this was probably about 40 years ago and the next best time is right now,” he said.

“You would think that the Arctic is this remote location that’s not really impacting anyone. But, through these carbon feedbacks and positive climate feedbacks, it is impacting us all,” Dr. Anna Virkkala, a research scientist at Woodwell and co-author, said.