You may think that cheating is a particularly human trait, but nature is rife with all manner of flora and fauna pulling the proverbial wool over each others eyes. It is the subject of a new book by Lixing Sun, a distinguished research professor in behavior and evolution at Central Washington University.

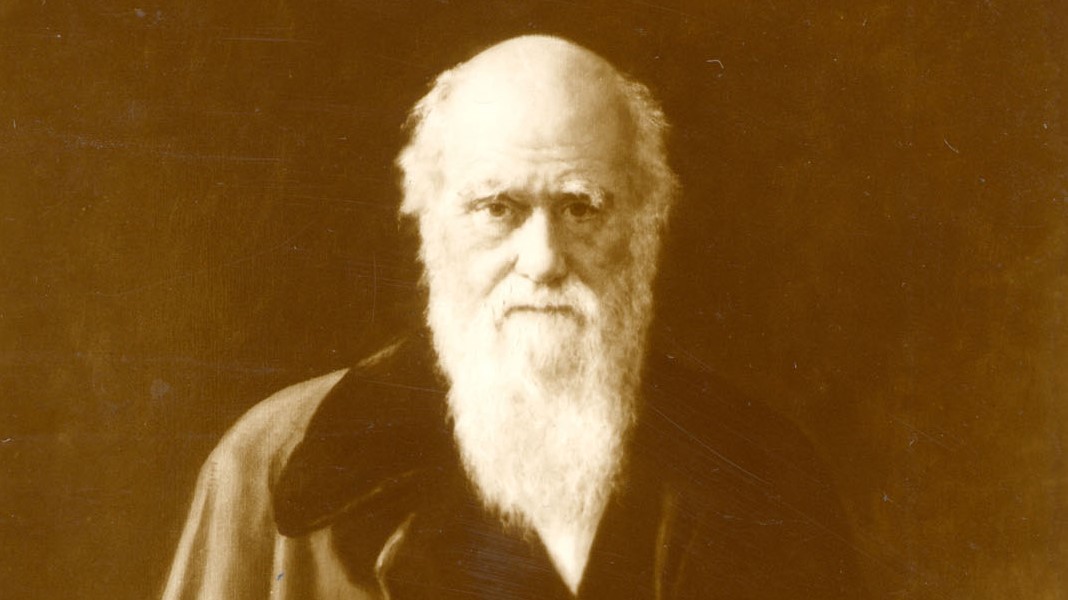

In The Liars of Nature and the Nature of Liars he explores how cheating evolved in the animal kingdom and why this dishonesty between species gave rise to the incredible diversity of life on the planet. Below is an extract from the book, where the author shows why even Charles Darwin may have overlooked the important art of deception in natural selection.

Cheating is found in all domains of life, at every level of the biological hierarchy, from the most complex organisms to the least sophisticated, even incomplete, forms of life. It is found among animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, viruses, chromosomes, genes, and snippets of DNA. It occurs within the same individual, between individuals of the same species, and between species that are vastly different in form and function.

Regardless of their prevalence in nature, however, the words cheating, lying, and deception all come with negative connotations due to our moral preference and the premium we place on honesty. Although we value truth and loathe lies, real life often runs counter to what we ideally want. Contrary to the long-held dictum, honesty is not always the best policy in our daily lives.

Consider this case. An innocent man has been falsely charged, convicted, and condemned to die. Desperate to save him, his loyal friends propose a way out: escape by bribing the jailer. Even when faced with this choice, however, he declines on the ground that to do so would be cheating the legal system. What do you think about the concept of honesty as applied by this man? If you were in his position, what would you do?

Why is cheating so common in the biological world? The answer: evolution is not a Socratic philosopher

If you think the man's choice is foolish, congratulations! You've just saved the life of Socrates, the Greek philosopher who chose death over breaching the trust between a citizen and the state. How likely is it that we would find a heroic martyr, willing to die for the sake of trust and honesty, in the natural world? Extremely unlikely — in fact, no known examples exist. On the contrary, we find that cheating is ubiquitous in nature at all levels.

Why is cheating so common in the biological world? The answer: evolution is not a Socratic philosopher. It is, instead, an unmoral, heartless process that proceeds pragmatically without any concern over ethical preferences, honor codes, or value systems. It certainly makes no distinction between prosocial cooperation and antisocial manipulation, because all that matters is what works to enhance survival and reproduction.

Related: Why haven't all primates evolved into humans?

Any trait — be it morphological, physiological, behavioral, or genetic — can prevail as long as it can boost its owner's Darwinian fitness, defined and measured as the number of offspring born and raised to adulthood. Furthermore, while freeing cheating from our moral consideration, evolution punishes those who forgo it as a strategic option when using it can increase their fitness. As a result, even though it might seem brazen and despicable to our human social sensibilities, cheating thrives in the biological world.

So, cheating flourishes in nature as a direct result of natural selection. Less well-known, however, is that cheating also serves as a potent selective force that drives evolution on its own. The reason is simple in concept: cheating favors the cheater and hurts the cheated. As such, it spurs the emergence of counter-cheating tactics, which in turn beget counter-counter-cheating strategies, ad infinitum. And during this ongoing evolutionary arms race, to quote Darwin, "endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved."

To illustrate this point, take cheating in rhizobia, soil bacteria that live in the roots of plants — specifically legumes. These bacteria fix nitrogen for plants, whereas the plants provide housing facilities and food in the form of carbon. So, the relationship is supposed to be happily mutualistic — or so we traditionally thought. But a close examination has revealed that, rather than a love affair, the relationship between rhizobia and their plant hosts is far more complicated. Some rhizobia actually produce very little nitrogen. That is, they cheat in order to get free housing and carbon from the plants. For this reason, not all plants welcome rhizobia. Some are known to fight back by cutting off the nutrient supply if cheating rhizobia are too numerous. Only those living in poor soil, desperately in need of nitrogen, would grudgingly put up with an unfair relationship with rhizobia. Apparently, beggars can't be choosers. This demonstrates how cheating can unleash a cascade of new moves and countermoves as the bacteria and their hosts try to get the upper hand in their relationship.

...evolution has been popularly stereotyped as "survival of the fittest" and "nature red in tooth and claw." Such a one-dimensional impression tends to divert our attention from the soft power of cooperative behaviors...

Intrigued by the complex strategies emerging from the evolutionary game played by rhizobia and plants? This is just a simple case to illustrate how cheating can trigger an evolutionary arms race and become a powerful catalyst for the creation of diversity, complexity, and even beauty, as we will see in the following chapters. Unfortunately, the role of cheating in evolution remains underappreciated today for two key reasons. One is historical. Darwin himself did not address cheating as a major force in evolution by natural selection. "On the Origin of Species" never mentions the word "cheat" but uses the word "deceive" seven times. Only three are related to animal cheating — all are forms of mimicry, protective disguises employed by tasty bugs to fool their predators. Clearly, how cheating relates to evolution and biodiversity wasn't on his mind — at least not high in priority among his many ideas.

Darwin's omission implies the second reason for us to overlook the importance of cheating. It's easy to see natural selection in terms of unrelenting, cutthroat competition for resources between rivals, or in terms of surviving the onslaughts of predators, parasites, and pathogens. Because of this, evolution has been popularly stereotyped as "survival of the fittest" and "nature red in tooth and claw." Such a one-dimensional impression tends to divert our attention from the soft power of cooperative behaviors that are fully as effective for enhancing fitness in numerous situations and contexts, a point made clear by many scientists during recent decades. In some animals, social intelligence is significantly more important than physical strength.

In a bonobo group, for instance, success in terms of fitness is predicated on the strength of an individual’s social network. A brawny brute who relies on sheer individual muscle power is destined to be a loser when faced with the united efforts of cooperating members of the group. Without some needed social intelligence, he could also become an object of manipulation, exploited by others. This is why cheating, a catalyst for social intelligence, matters so much in evolution.

Text from THE LIARS OF NATURE AND THE NATURE OF LIARS by Lixing Sun. Copyright © 2023 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.