When I was 2, my parents and I moved from Chicago to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where plutonium for the atomic bomb was developed from 1942 to 1945.

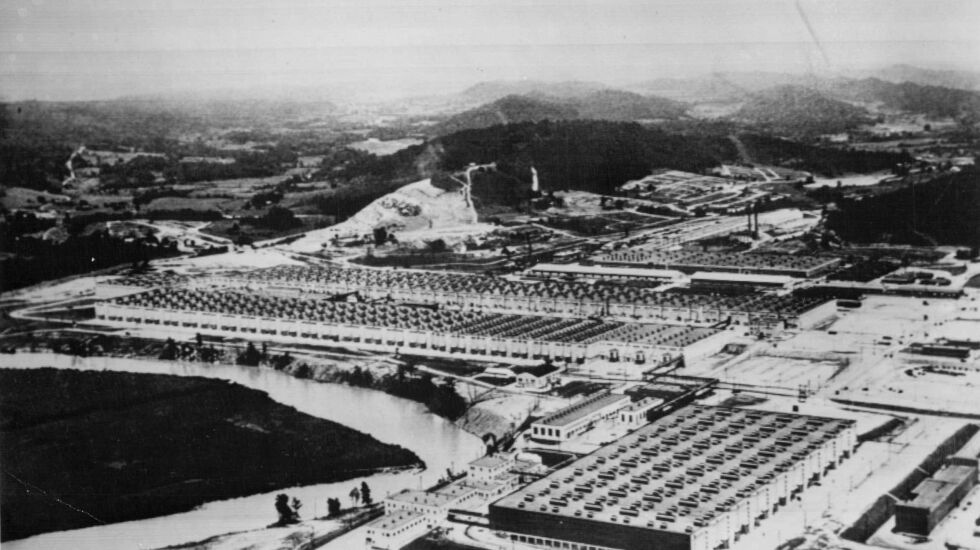

The land, from which farm families were displaced with two weeks’ notice, initially was as empty as Los Alamos back then, an unlikely place for a major government project, but perfect for a secret project.

As one character said in the film “Oppenheimer,” it needed a bar. But, as 75,000 workers arrived, the government quickly built recreation centers, bowling alleys, grocery stores and even supported a symphony at this remote location 15 miles west of Knoxville.

My folks, intrigued as others were by the lure of good wages and a government job, also were drawn by the prospect of helping with the war effort, although they didn’t know the massive extent of the project. My father was hired to manage an electrical warehouse.

Oak Ridge was the strangest place to work. The site was chosen for the X-10 Graphite Reactor, used to produce plutonium from natural uranium for the Manhattan Project. Fences and guard towers surrounded the city. Mail was censored. Comings and goings were strictly monitored. No one was allowed to know the purpose of their work and reminders of secrecy were posted everywhere.

One sign showed three monkeys, illustrating the words:

What You See Here

What You Do Here

What You Hear Here

When you Leave Here

Let It Stay Here

One night my father told my mother he wanted to tell her a secret about the camp, but she couldn’t share it with anyone. “Then don’t tell me because I’m not good at keeping secrets,” she replied. He never spoke about Oak Ridge again.

The bombs killed and burned hundreds of thousands of people in Japan and a debate rages: Were the bombs and the world of destruction they introduced necessary? President Harry Truman said the bombs saved 250,000 American lives that would have been lost in an invasion of Japan.

The film shows the mental torment of Oppenheimer after the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The government revoked his security clearance in 1954 due to his association with progressive causes and his opposition to the development of the hydrogen bomb. A heavy smoker, Oppenheimer died at age 62 of throat cancer.

My family’s involvement with the bomb did not end when we drove away way from Oak Ridge in 1945 back to our roots in Chicago, where Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago had achieved the first scientific advancement that set the stage for the atomic bomb.

Nor did Americans’ involvement with the bomb end at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Everyone everywhere continues to be affected.

At a family party in Wisconsin in 2018, my cousin, Rosemary, the family chronicler, said, “Your father didn’t die from smoking. He died from exposure to toxins at Oak Ridge.”

I dismissed her theory because my father smoked two packs of Chesterfields daily and died of lung cancer at age 58, leaving us bereft and blaming those damn cigarettes. He had been an outstanding athlete, playing basketball for the University of Kansas Jayhawks, and excelling at sports his entire life.

As much as I thought my cousin was probably wrong, I contacted a lawyer in Tennessee who said my sister and I could file for survivor benefits from the government.

Near the end of the 1-1/2 year process, when our hopes were fading for recognition of our loss, I found a going-away card addressed to my father by the men he supervised at Oak Ridge. They said they’d miss him, his fairness, poker games and betting pools. They signed it with only their last names.

I don’t know if, after months of back-and-forth paperwork, a bureaucrat was convinced by this relic of camaraderie and the names of specific employees who worked with my father, but shortly after, my sister and I received substantial checks. No amount of money would ever make up for the loss of an exceptionally strong and agile father when we were 18 and 15.

Along with the 220,000 Japanese citizens killed in 1945, people living near the testing site, my father, Oppenheimer, and other Americans also made sacrifices. The American government spent billions rebuilding Japan after the war. Ultimately, other countries developed bombs.

The mushroom cloud from the bombs contaminated the atmosphere forever. The threat of nuclear war hangs over our heads. The film’s depiction of Oppenheimer’s angst resonates with us today.

Linda Landis Andrews is the internship coordinator for the English department at the University of Illinois Chicago.

The Sun-Times welcomes letters to the editor and op-eds. See our guidelines.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chicago Sun-Times or any of its affiliates.