In September 2006, a US military C-17 cargo plane arrived at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba and deposited 14 new prisoners. The men had previously been held in CIA “black site” prisons around the world, where many were tortured outside the protections of US law.

One of them was Ammar al-Baluchi, one of the five men facing a military tribunal at Gitmo for allegedly aiding the 9/11 hijackers. Prior to arriving at the island prison, Baluchi was subject to isolation, forced shavings, beatings, dousings with ice water, stress positions including being shackled to a ceiling, and food denial. In one particularly disturbing incident, trainee interrogators formed a line and repeatedly slammed his head against a wall for practice in a technique known as “walling,” leaving him with brain damage, according to a CIA report declassified in 2022.

When he arrived at the island US naval base alongside the 13 others, they were spirited to an equally shadowy lock-up: Camp 7.

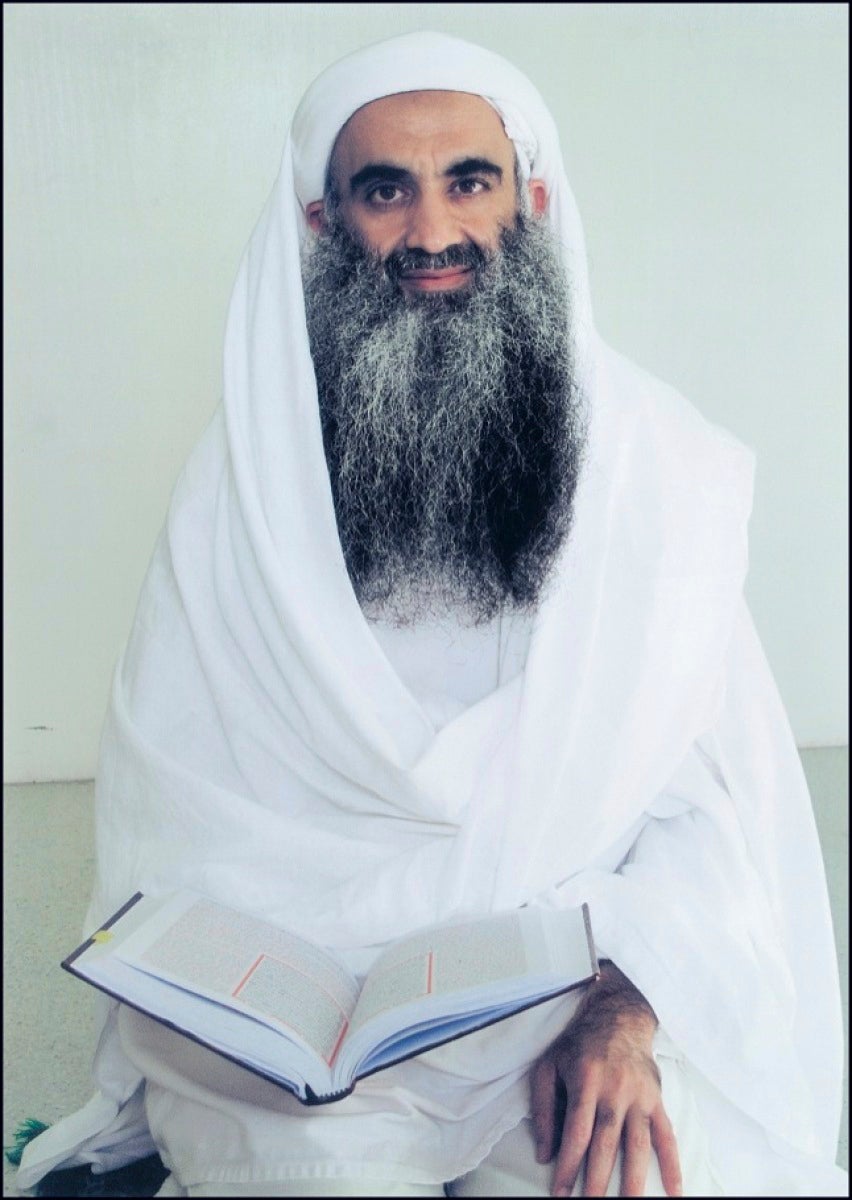

Camp 7, before it closed in 2021, was the most clandestine part of Gitmo, so closely guarded its exact location, design, and costs were secret. It held some of America’s most high-value detainees, including Baluchi and his uncle, 9/11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed.

Nearly two decades after those prisoners arrived at Guantánamo, a new lawsuit could reveal more about what went on inside, and whether it was under the full “operational control” of the CIA.

On Monday, the American Civil Liberties Union asked the Supreme Court to take up Connell v CIA, which argues that the intelligence agency was wrongly able to dodge a records request about its ties to Camp 7. What might seem like an arcane legal fight about records policy has the potential to shed new light on one of the ongoing secrets of the War on Terror.

The case stems from Baluchi’s legal defense. Baluchi, who was born in Kuwait and captured in Pakistan in 2003, is accused of providing money and travel arrangements for the 9/11 hijackers at the request of his uncle. The Kuwaiti has said he didn’t know for certain what the recipients of his support were planning to do, and hasn’t been convicted of any crimes.

In 2017, Baluchi’s lawyer James G. Connell III filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the CIA, seeking information about his time being detained in Camp 7, a facility the 2014 Senate torture report later described as being under the “operational control” of the CIA at the time Baluchi arrived. The agency replied with three records, but withheld a fourth in its entirety, and it refused to clarify whether any further records linking the CIA and Camp 7 even existed.

The ACLU argues the CIA’s non-denial denial, its cliched “we can neither confirm nor deny” response known as a “Glomar” defense, defies common sense because the torture report, Guantánamo Bay military commission testimony, and declassified documents all suggest CIA activity at Camp 7.

“The CIA’s claim to secrecy in this case is as extreme as it is absurd, given the extensive public record about the CIA’s connection to Camp 7,” Brett Max Kaufman, one of the ACLU attorneys arguing the case, said in a statement. “The CIA has once again stretched Glomar past its breaking point, and the courts should not be roped into endorsing a patent secrecy charade like this one.”

The Independent has contacted the CIA for comment, and the Defense Department referred requests for information to the intelligence agency.

Some lower courts have so far sided with the CIA, finding that in records cases, judges need not look further afield for information that might contradict an agency’s silence. The ACLU argues, however, that appeals courts are split on the matter, and judges shouldn’t have to "bury their heads in the sand” if there are indications that an agency is refusing to acknowledge, and potentially divulge, information it likely possesses.

The civil rights group argues the CIA regularly abuses the Glomar defense, using it to deflect inquiries on controversial issues like drone strikes, extrajudicial killings of US citizens, and questions of potential spying on Congress.

What is public about Camp 7 and the CIA’s activities at Guatánamo is concerning to many observers.

In 2019, a former commander testified in the 9/11 case that the detainees there were guarded by a secret unit, called Task Force Platinum. The unit wore US military uniforms with pseudonyms instead of names and no marks of rank, suggesting to observers they were CIA agents or contractors posing as soldiers. (At the same hearing, a former Army officer called by the government testified that he and his troops took custody of the prisoners when they arrived, further muddying the picture who was actually in control of Camp 7.)

There are also questions of whether the detainees at Camp 7 suffered further civil rights abuses during interrogations at the naval base. At Guantánamo, the former CIA torture victims were interrogated again, this time by FBI agents sent in 2007, in the hopes that the government could extract information without the use of torture so it would later stand up in court.

Defense lawyers have argued evidence from these FBI interviews is tainted too, since detainees were held in conditions much like their past time in black sites, potentially overseen by the same agency, the CIA. The detainees may have been unaware they could refuse to comply with these interviews or afraid they would be tortured again.

Moreover, there’s evidence that the FBI was involved in the original international black site interrogations at CIA prisons where torture took place. An FBI agent has testified in 2019 to sending hundreds of questions to the network of secret prisons where men like Baluchi were tortured before they were flown into Guantánamo.

Camp 7 closed in 2021, but the records fight is only one front in a much larger legal war over the government’s conduct hunting the men who carried out 9/11.

Revealed: First Image of War on Terror Detainee in CIA Black Site

— Mansoor Adayfi 441 منصور الضيفي (@MansoorAdayfi) August 2, 2024

Today, we confront a stark and haunting image that lays bare the grim realities of what is called the war on terror. This photograph, the first of its kind to be published, shows Ammar al-Baluchi, confined at a CIA… pic.twitter.com/SrHiwCBwQz

In August of this year, it was Baluchi who appeared in the first publicly released photo of a black site detainee, standing naked and gaunt in shackles with his head shaved, part of a trove of some 14,0000 such black site images reportedly in the government’s possession that mostly remain secret. Baluchi’s torture inspired scenes in the 2012 film Zero Dark Thirty, and remains a live issue in the ongoing 9/11 capital case, where defense lawyers have long argued evidence obtained under torture should be inadmissible.

Resolution in any of these matters seems far away. In August, the Defense Department canceled an apparent plea deal involving Mohammed and two others, though it was reinstated on Wednesday. The 9/11 trial of the remaining defendants may not start until 2026.

Whatever form this chapter of the post-9/11 reckoning takes, and whenever it takes place, it’s clear that even decades after the height of the War on Terror, many secrets are still being kept – and the US is maintaining its silence.