Sometimes, when we take certain decisions, we get more than what we bargained for. This unforeseen turnaround is especially striking when a political leader triggers an electoral process which, along the way, is redefined by the opposition or by the citizens.

We have seen this in the case of referendums that were intended as mere ratification procedures. Take the unexpected victories of the “No” vote in the plebiscites on the Maastricht Treaty in Denmark in 1992, for example, or on the European Constitution in France and the Netherlands in 2005. We saw it in the surprise approval of Brexit in the United Kingdom in 2016, too.

In these examples, the result was the opposite of what was expected, as voters cast their ballots to punish the government, protest against the elites or vent national anger rather than pronounce themselves on the issue at hand.

This repurposing can also impact on other elections. This was partly the case of the Spanish municipal and regional elections on 28 May.

For many people, the ballot did not decide the local or regional future: it was simply a referendum on the continuity of the socialist government. The opposition’s ability to focus the debate on the government of Pedro Sánchez resulted in a victory for the (ultra-)conservative bloc in almost all the fiefdoms at stake.

This is also how Sánchez himself understood it. To prevent the defeat from turning into a tsunami, the following day he called a general election for 23 July.

Almost a century ago, another call for local elections led to the fall of the Spanish Monarchy and the birth of the Second Republic.

The Republican 14 April

Under the Bourbon Restoration (1874-1931), all elections in Spain were won by the party that called them. These victories had little to do with luck or political merit and everything to do with a series of carefully crafted political mechanisms that ensured continuity.

Among them, the “peaceful turn”, a pre-agreed alternation in the government of the conservatives and the liberals, ensured that both parties would get to govern every other legislation.

Another one, the encasillado, saw designated ministers from the incoming government allocate seats to MPs in a bid to help them secure the comfortable majority required to govern.

Finally, the caciquismo, which extended its tentacles well into the 20th century, established clientelist relationships between politicians and powerful people in different regions, facilitating frauds in the general elections.

However, the system gradually deteriorated, reaching its worst point under the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–1930).

Deeply unpopular under the dictatorship, King Alfonso XIII sought to burnish his credentials by returning to the previous political system. The ruler began by calling local elections. Convinced that they were less bureaucratic and closer to the people, Alfonso XIII also thought they were least prone to political surprises.

A majority of citizens begged to differ, however, turning to the ballot boxes to speak out against the continuity of the House of Bourbon.

Elections were held on 12 April 1931 and the count took some time. Two days later, the 14th of April, the Second Republic was proclaimed.

What mattered was not the overall result. The regime won the majority of councillors by dominating the more rural provinces, where elections often only comprised of one candidate and were therefore prewritten. The important votes were the ones where universal male suffrage – women’s suffrage was still not allowed – could freely express its choice. That is, mostly urban areas.

In Madrid and Barcelona, the Republican opposition managed to respectively triple and quadruple the scores of monarchist candidates. The triumph reverberated in the majority of provincial capitals, turning the plebiscite into the “elections that ended the monarchy”.

The episode long stuck with the Spanish political class. In fact, when the historical circumstances were repeated, that memory was a major conditioning factor. Seeking to transition from a dictatorship to a democratic regime after Franco’s death, the government of Adolfo Suárez delayed the local elections until 3 April 1979.

In the meantime, Suárez called two referendums (a political reform law in 1976 and on the constitution in 1978) and two general elections (the Constituent Assembly in 1977 and the first legislature in 1979). That meant that local and provincial councils maintained their Francoist composition for more than three additional years after the dictator’s death.

A coin toss

There are also precedents of electoral gambles that paid off.

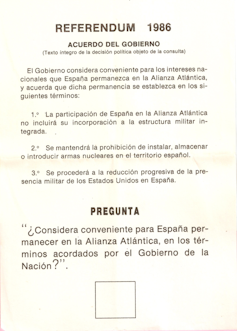

On 12 March 1986, prime minister Felipe González honoured his electoral pledge by calling a referendum on Spain’s membership of NATO. The plebiscite was to testify of a change in the position of the socialist (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, PSOE) leadership, leaving behind its initial “NATO, no from the outset”.

The opposition, however, had other ideas, and attempted to frame the referendum as an opportunity to undermine the government’s absolute majority and a first round of the general elections scheduled for that same year.

Thus, the entire left wing of the PSOE actively called for a “No” vote. They were joined by some dissident leaders, the Socialist Youth and the (then still) sister union of the UGT. The Popular Coalition (PC) – the forerunner of today’s conservative Popular Party (PP) – advocated abstention to pile pressure on the government, and Jordi Pujol’s conservative CiU went so far as to discreetly campaign in favour of a “No” vote to wear down the socialist government.

Some would voice regret years after these tactics discredited them both at home and abroad, and above all, failed to achieve their goal.

Although the “No” vote won in Catalonia, the Basque Country, Navarre and the Canary Islands, “Yes” triumphed overall with 56.85%. Much to the delight of the opposition at the time, González had gone so far as to condition his continuation on the final result… and he won.

Moreover, not only did he overcome the abyss of the plebiscite, but he also took advantage of the changing tide. He brought forward the elections from November to June and renew, despite losing 18 seats, the absolute majority of 1982.

Regardless of who ends up losing out on 23 July, the fact is that such agonising approaches alienate citizen consensus and democratic quality.

Jaume Claret does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.