Today, the federal government is due to report back to UNESCO on its efforts to protect the Great Barrier Reef. The government’s announcement last week of A$1 billion of additional funding is welcome, but it will do little to allay UNESCO’s concerns.

Climate change is the number one threat to the Great Barrier Reef. While the new funding is meant to address other threats to the natural wonder and may improve its resilience, failing to address the climate threat is both disappointing and nonsensical.

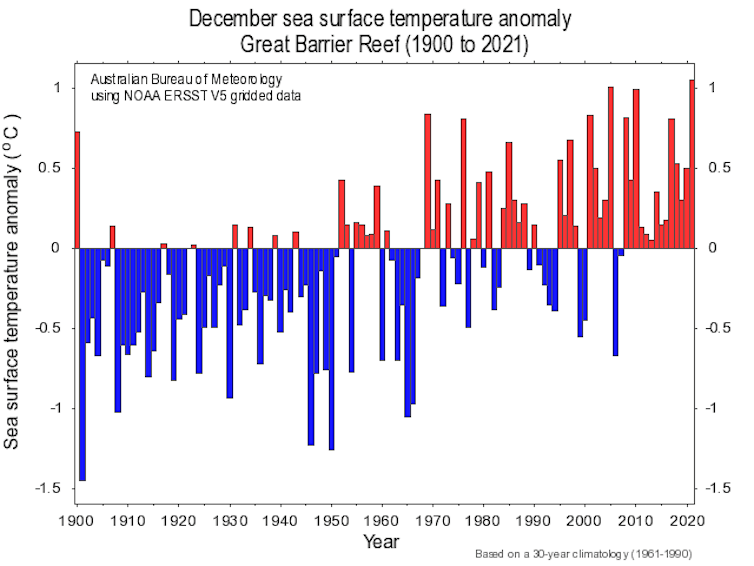

As the below graph shows, ocean temperatures on the reef in December last year were the warmest on record. With this comes the risk of a fourth mass bleaching event this decade.

The Great Barrier Reef came close last year to being put on a list of World Heritage “in danger” sites. The funding announcement seems primarily about appeasing UNESCO, with one eye also on the upcoming federal election. But saving the Great Barrier Reef is not about throwing money at it – what matters is how the dollars are spent.

By the numbers

The $1 billion package proposed by the government comprises:

58% to address the land-based causes of water quality issues impacting the World Heritage Area

26% to reduce crown-of-thorns starfish and prevent illegal fishing

9% for new scientific technologies

7% allocated to local communities – including Traditional Owners – for habitat restoration, citizen science and reducing marine debris.

The measures to be funded are all important. But they’re nowhere near as important as addressing the root cause of climate change: greenhouse gas emissions. Most of the $1 billion should have been used to help Australia phase out fossil fuels.

What’s more, the federal and Queensland governments continue to approve new coal and gas projects. Doing all this, while knowing the grave threat climate change poses to the Great Barrier Reef, demonstrates the incoherence of government policies.

Devil in the detail

When we drill further into the detail, it becomes even more clear the funding package is not as impressive as it may first appear.

The $1 billion funding has been allocated over nine years. This is far beyond the time frame to which any government can sensibly commit, given four-year election cycles. A major funding increase is needed urgently, and certainly within a single term of government.

Also, federal Labor’s funding proposal for the Great Barrier Reef must be increased.

Another concern is the funding allocation for new scientific technologies such as coral seeding, developing heat-resistant corals and cloud brightening. Some of these technologies may have produced positive results at a small scale. But none has yet proved feasible at the wide scale necessary to make a real difference for the Great Barrier Reef.

Efforts to address water quality are important. After climate change, poor water quality is the most pressing problem facing the reef. It’s largely caused by nutrients, pesticides and sediment runoff from agriculture and coastal development.

Read more: Not declaring the Great Barrier Reef as 'in danger' only postpones the inevitable

But governments have already spent hundreds of millions trying to improve water quality, with only limited success. Reducing water pollution requires more effective spending, not just more funds.

This is just one example of how money alone cannot fix all the Great Barrier Reef’s problems. Improving water quality requires the right balance between voluntary industry-led approaches and enforcing the rules.

The Queensland government must greatly increase its compliance and enforcement on matters such as fertiliser runoff entering creeks that flow to the reef. While many farmers are doing the right thing, others clearly are not.

And to improve water quality, governments must be prepared to limit clearing and agriculture expansion in reef catchment areas.

Learning from our mistakes

For years, the federal government has known the pressures facing the Great Barrier Reef. But it continues to maintain a “business as usual” attitude in the face of the worsening climate crisis. Governments worldwide must dramatically increase their climate ambitions – and for the Great Barrier Reef, this action should start at home.

As the Murray-Darling Basin experience shows, throwing funding at an environmental catastrophe does not fix the problem, especially if the core issue remains unaddressed.

The government must also better allocate funds to achieve effective and timely “adaptive management”. This involves decision-making that can be adjusted as outcomes become better understood.

Such management should include considering both the good and bad outcomes of reef interventions to date – both those controlled by government agencies and those managed by external groups such as the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

This latest government funding boost is welcome, but suspiciously timed. Environmental policy and budget allocations should not be about a government’s reputation and firming up its electoral prospects – especially when so much is at stake.

UNESCO is likely to welcome the additional efforts to address water quality. But it has specifically urged Australia to take “accelerated action at all possible levels” to address the climate threat. It remains to be seen whether UNESCO will continue to pressure the federal government on that front.

Amid all this, a key question remains. As the the Great Barrier Reef continues to decline, will Australians re-elect a federal government that supports industries harming the environment?

One thing is certain: Australians, and their Great Barrier Reef, deserve so much more.

Read more: 5 major heatwaves in 30 years have turned the Great Barrier Reef into a bleached checkerboard

Jon Day previously worked for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority between 1986 and 2014, and was one of the Directors at GBRMPA between 1998 and 2014. He represented Australia as one of the formal delegates to the World Heritage Committee between 2007-2011.

Scott Heron receives funding from the Australian Research Council and NASA ROSES Ecological Forecasting.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.