Big-city traffic and a resolution on New Year’s Eve of 2020 led Pflugerville resident Kelsey Black to become a bookseller.

An avid reader, she disliked the hour round trip required to get from her suburb of 65,000 to downtown Austin to browse a bookstore. “OK,” she told herself, “I think it’s just going to be easier for me to … start my own bookstore.”

Turned out, it wasn’t easy at all, “but it’s OK because I have now found my calling,” Black said. The Book Burrow began as a pop-up and online business and finally, on August 6, opened as a brick-and-mortar store. She said the 200-square-foot space has become a haven for those who don’t feel like they fit in elsewhere, drawn by the store’s motto: “Embrace your weird.” For her, the phrase means cultivating love for whatever makes you unique: “Embrace your gender identity; embrace your sexual identity; embrace your racial background; embrace your spiritual path.”

Apparently, she is good at creating a welcoming atmosphere. Multiple strangers came out to her the day the Burrow opened its doors. “We have a story for everybody in our little bookstore,” she said.

New independent bookstores in Texas are blossoming as in the rest of the country, and many of the more established ones are “hanging in there” by writing and rewriting their own stories. A passion for books and people and a willingness to embrace change seem to be among the key requirements. Many managers talk about retooling their businesses to survive the COVID-19 pandemic. Some stores had to rethink who their customer base was and find new allies. And it looks like book-banning efforts in this state aren’t all that bad for the indie bookstore business.

“We have a story for everybody in our little bookstore.”

“It definitely seems like bookstore openings are on the uprise again. I just heard [of] about four more,” said Kristine Hall, publisher of Lone Star Literary Life, which covers independent bookstores in Texas. When she went to a regional conference in April, she said, “Booksellers there said they are stepping up their sidelines, which account for a lot of their revenue.” Overall, the industry is just always “on and off, on and off,” she said. “And there’s always the Amazon anti-Christ.”

In many cases, surviving and thriving has meant developing a second line of business, becoming a “bookstore and”—a bookstore and a coffeeshop. A bookstore and a gift shop. Or art gallery. Or wine seller. North of Abilene, in the small town of Stamford, the Noteworthy bookstore and gift shop actually helps support the local newspaper whose offices it shares. In Fort Worth, Leaves Book and Tea Shop probably sells as much Earl Grey as it does books, but its stated mission is one shared by just about every indie bookstore: to “create a community gathering place where you can pause from the hectic pace of daily life.”

Julia Green, manager of Front Street Books in Alpine, said that according to the Mountains and Plains Independent Booksellers Association, registrations of new members are up. “We’re gaining more than we’re losing,” she said.

Front Street, in one incarnation or another, has been around since about 1996; Green has worked there for most of that time. On a recent, crisp morning, the bookstore was busy. People came in the front door or from the back, where the bookstore connects to Cedar Coffee Supply.

“We get a ton of business, people wandering back and forth” between coffeeshop and bookstore, Green said. The store offers sections on Texas-Mexico border issues, women’s issues, LGBTQ+ authors and topics, and other interests. The shelves of traditional mysteries and romances are near the back of the store.

“Our goal is to be a welcoming space regardless of your politics,” she said. People should be able to “find a home here, find a book here, regardless of what you believe or what we believe. … That is something true to indies. It’s kind of our whole point.”

Green said the store has never gotten complaints or threats because someone didn’t like the books they offer. But then, she said, she has heard of no attempts to ban books in Alpine schools or libraries, as has happened in many allegedly more cosmopolitan areas.

By contrast, Black said someone once complained to the Pflugerville mayor that the Burrow was “promoting Satanic ideology” at a farmer’s market event because of a book whose cover showed a part-woman, part-scorpion hybrid, “and that we can’t have that in a Christian nation.” The mayor called the farmer’s market manager, who looked at her table, and then, Black said, had a laugh with her over it.

In some markets, Hall said, book-banning attempts have actually helped independent bookstores by “giving them a campaign to throw themselves behind.” In that context, she said, “bookstores are safe places.”

In San Antonio, the Nowhere Bookshop, founded by author Jenny Lawson, reacted to a local school district’s book-banning attempt by offering to donate up to 250 copies of the book in question—the award-winning Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford—to local educators.

Manager Elizabeth Jordan said more than 120 educators have signed up thus far for the free copies and that people have expressed interest in donating to the effort. “We … hope we have created an environment that makes Nowhere feel like a safe space for historically marginalized communities,” she said. The store opened to curbside business in 2020 in the midst of the pandemic. The physical store, which offers a coffee, wine, and beer bar, opened in July of this year.

“The biggest reason we got through 2020 was the neighborhood wanting to support its bookstores.”

Dallas seems a thriving locale for indies. Deep Vellum Bookstore (in Deep Ellum, of course) and the publishing house of the same name call themselves “the heart and soul of the literary community in Dallas,” a boast backed up by the bookstore’s calendar, filled with information on readings, author interviews, and exhibits. Interabang Books, in North Dallas, has survived a tornado and flooding as well as the pandemic and is now at a point where it’s doing “extremely well,” according to the store’s business manager. On the west side of town, the Bishop Arts District now boasts four or five indie bookstores, including the tiny Poets Bookshop.

Poets is owned by the same trio who owns Cigar Arts next door, which has been around for about a decade. When the neighboring space became vacant in 2017, co-owner Marco Cavazos said, they opened up a hat shop “because we thought hats would be a cool fit for the neighborhood.” Their mistake, he said, was that “we weren’t passionate about hats.” So they turned to books, which all three were passionate about. The cigar shop and bookshop are mostly separate, business-wise, Cavazos said, rather than either one depending on the other.

Cavazos, who writes both poetry and fiction, originally envisioned the shop as a collaborative poetry studio where people would come to write—on manual typewriters, no less—read, and create art. Adding a book component “just made sense,” he said, even more so because the pandemic quickly put a stop to shared workspaces. So the bookstore continued, with books getting delivered to local customers. “The biggest reason we got through 2020 was the neighborhood wanting to support its bookstores,” he said.

A few blocks away, The Wild Detectives bookstore has been a wild success for years because it’s also a bar and an event venue. On a Sunday afternoon, the backyard of the little repurposed house was full of chess players, readers, students studying, and a family birthday party. A few kids ran around, and someone tended to a cocker spaniel in a baby carriage. Inside at the bar, an artist was sipping a drink and sketching, and customers were lined up to order drinks and food and pay for books. The space at the front of the room, often set up for poetry and prose readings, was reconfigured for the daytime crowds.

In North Dallas, business manager Brian Weiskopf said Interabang is “doing extremely well. It’s nice to have writers back on the road. … We have a vibrant signed first-edition club. And we’ve also rolled out a child subscription program” for their youngest readers. People love the convenience of Amazon, “but they also love the feel of a real book,” he said. “They like our expertise … that personal touch.”

What’s in the future? “I’ve heard that many people would love to have this kind of bookstore on their side of town,” he said. “We’d love to expand our footprint. But we can’t do it right now.”

Other store owners say they are maintaining rather than looking to expand. BookWoman, Austin’s original feminist bookstore, is at that stage, according to owner Susan Post. On the other hand, that’s what they’ve been doing since 1975, sustained by the locals’ love for its eclectic selection and its storied history. The business began as part of the great feminist bookstore movement, which saw hundreds of similar shops pop up around the country and internationally in the 1970s and ’80s. Post said fewer than a half-dozen stores from that time remain.

There was a moment early in the pandemic when the store flourished, she said, as disrupted supply chains sent people looking for new, local sources for what they needed. The store’s small footprint and minimal staff meant BookWoman was able to stay open with curbside pickup when other bookstores were forced to close.

She recalled a day when the counter was piled high with orders ready to be mailed. “We must have shipped like 30 boxes of books,” she recalled. “And it went on like that for a year.”

The rush is over now, however. “Now that’s really fallen off because people are socializing, going to movies, going on vacation,” Post said.

Still, the store cultivated new, loyal customers during that time and diversified into new income streams, from t-shirts to a non-Amazon-owned company that lets customers order audio books alongside the traditional kind. BookWoman, like many stores, has also partnered with bookshop.org, an online bookseller that shares 30 percent of sales with brick-and-mortar stores. The site generates a small income for her store, Post said, “but we make more if they order directly through our website.”

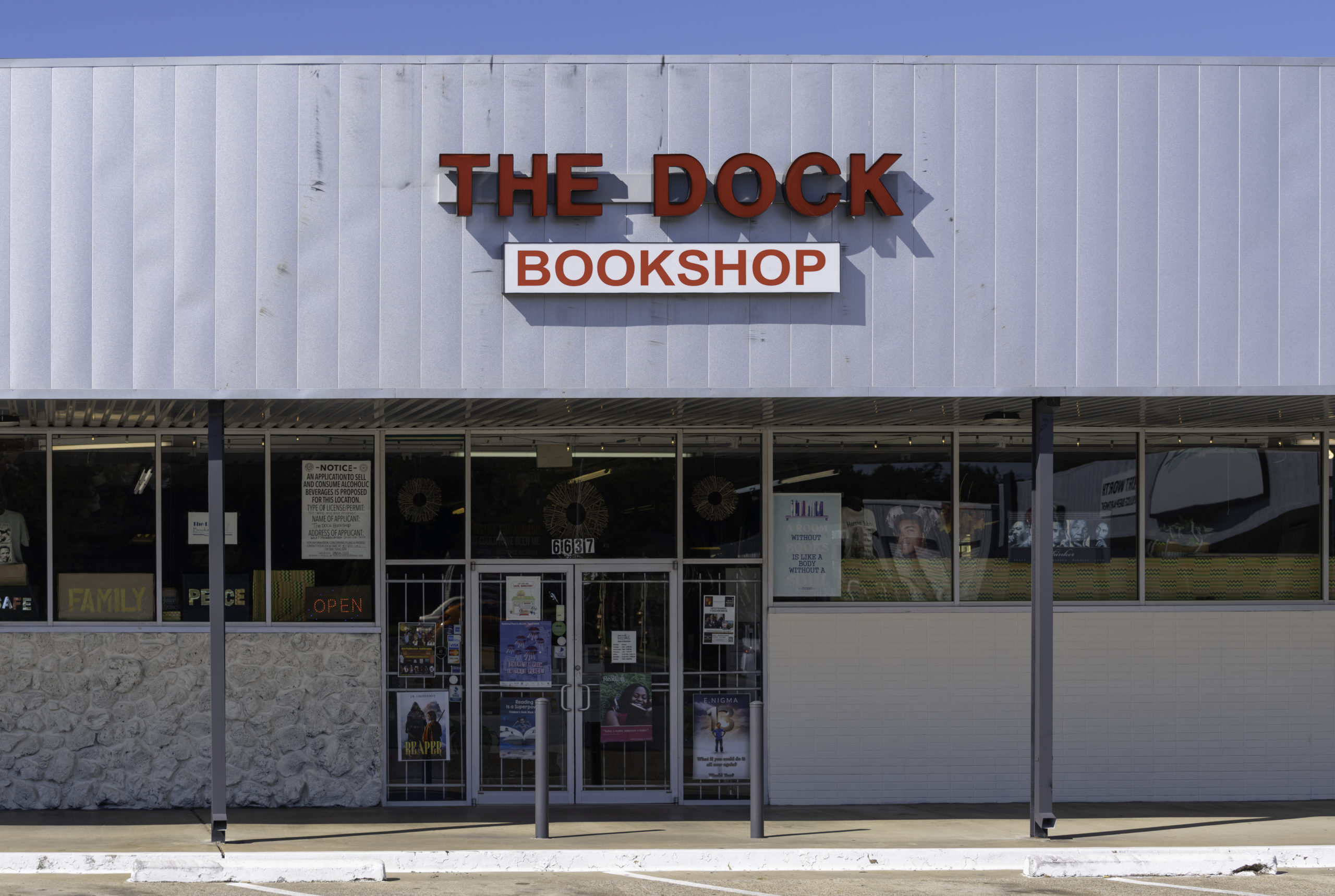

In Fort Worth, The Dock Bookshop is also “maintaining,” said Donna Craddock, who owns the roomy eastside store with her sister Donya. As one of the largest African American-owned full-service bookstores in the state, The Dock does on a larger scale what many smaller stores, like Book Burrow, also do: try to offer something for everyone while also providing in-depth material for underserved groups. They also have a large section of children’s books. Since the store opened in 2008, Donna said, they’ve watched some young customers grow up. “We do have some bookstore babies,” she said.

When the pandemic started, Donya Craddock said, The Dock had already embraced a variety of platforms to bring customers in, including podcasts like the Dock Power Hour. Still, she said, “a lot of people weren’t working, and books were not in the hierarchy of need.”

The Dock was close to shutting its doors when a national tragedy changed things. On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and a movement that the Craddock sisters call “a great awakening” rolled into The Dock.

“People were willing to break down walls and try to learn about other groups. People were grappling with this thing called racism,” Donna said. And to learn, they came to The Dock.

“This section here,” she said, pointing to shelves of books on race relations, “we didn’t have this section”—that is, not nearly as many books on that topic. “It just blew up on us. … It was awesome.”

Included in that wave were a lot of European Americans. They’d had some of those customers before, Donna said, but many more started showing up. “It helped save the bookstore.” That wave eventually subsided, but some new customers stuck around. Even with that, though, business still isn’t back to pre-COVID levels.

As it always has been, involvement with the community is a key to their survival, both women said. The Dock hosts community meetings, family book nights, spoken-word events, and author events. This year the store was a founding sponsor of the Trinity River Book Festival, in which more than 30 authors participated. “It was very well received and we will definitely be doing it again next year,” Donya said.

Across town, Leaves Book and Tea has also stabilized since the pandemic, owner Tina Howard said. “I believe as our society feels fractured in many ways, bookstores are still held as a place of ideas and perspectives,” she said.

The last two years brought plenty of change to BookPeople. Austin’s largest indie bookstore closed for the first few months of the pandemic, and CEO Charley Rejsek said that only now, in the closing months of 2022, does she feel that she can begin thinking seriously about the future again.

Since 2020, she said, BookPeople has redesigned its website, signed its first union contract, and renewed its community partnerships. This summer, BookPeople partnered with Austin Public Library to present Banned Camp, a series of summer events for all ages focusing on banned books. Rejsek said it was a huge success, and they’re looking for other ways to support libraries and educators in the future.

“These challenges are just getting stronger. And we are definitely here to stay, to keep selling the books,” she said. “We recognize the books that are being challenged are the books that we uplift and highlight and recommend to our customers on a daily basis.”

“We recognize the books that are being challenged are the books that we uplift and highlight and recommend to our customers on a daily basis.”

John Dillman, owner of Kaboom Books in Houston’s Woodland Heights neighborhood, said it helps to think of the book trade like farming, where the weather can never be predicted. Used books—his section of the indie bookstore scene—are particularly unpredictable, he said. In two years out 10, “something hits you in the right ear that you never saw coming.”

Dillman’s been a bookseller for 45 years, starting in New Orleans and driven to Houston by Hurricane Katrina. His Houston store was hit hard when the pandemic forced him to close to in-person traffic. He’s just hoping that inflation and rising rents don’t hurt him or his competitors. “Houston’s a great city and it deserves more bookstores,” he said.

At BookPeople, Rejsek was getting excited about the Texas Book Festival (“the best weekend of the year”) and the coming holiday season. She wanted to remind people “that where you spend your money is where you put your values.

“We’re still asking our community to … shop with us if they want to see us here,” Rejsek said. Supply chain issues, inflation, and other threats have not gone away. “We’re asking people to shop early and shop local this season and to resist Amazon.”