When “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” opened the Metropolitan Opera’s 2021-22 season, it created something of a sensation.

For starters, it was the first opera by a Black composer presented by the New York company, and the cachet of its creators certainly contributed: contemporary jazz legend Terence Blanchard, and librettist Kasi Lemmons, a noted film director and screenwriter.

But more important was the quality of the offering itself. That became readily apparent Thursday evening as Lyric Opera of Chicago opened its gripping take on this 2019 opera, just the second work by a Black composer performed on the company’s main stage.

When: 2 p.m. March 27; four additional performances through April 8

Where: Lyric Opera House, 20 N. Wacker

Tickets: $39-$319

Info:lyricopera.org

With a title taken from an evocative phrase in an Old Testament verse, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” is a sad, harrowing and ultimately redemptive tale based on the best-selling memoir of New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow.

It is a specifically Black story but it is also a universally human story that confronts issues of otherness and psychological trauma, focusing on a “boy of particular grace” in the rural South who struggles desperately to fit in.

Charles is haunted into early adulthood by the sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of an older cousin when he is 7 and the shame, anger and loneliness that followed. As the opera opens, he is given an opportunity for bloody revenge. Will he take it? That question hangs menacingly in the air as he looks back at his life.

Lyric’s version of “Fire,” a co-production with the Met and Los Angeles Opera, is co-directed by James Robinson and Camille A. Brown, who deftly give voice to the story’s gritty realism and emotional honesty.

Kudos to the dance scenes, which were originally choreographed by Brown and revived by Jay Staten—the ghostly dance fantasy at the beginning of Act 2 and the high-stomping, show-dance number in the Act 3 college scene.

Allen Moyer’s scenery is simple yet highly effective, relying primarily on transporting black-and-white and color images that are brilliantly deployed by projection designer Greg Emetaz onto three giant screens at the back and sides of the stage and parts of two giant interlocking boxes. At first, the open, barn-wood covered interior of the larger of the two boxes faces the audience with the slightly smaller one inset as its back panel, the whole unit serving as a kind of stage within the stage. Then, the two boxes are constantly rotated and reconfigured, with pieces of furniture and other set pieces added to evocatively set the scenes.

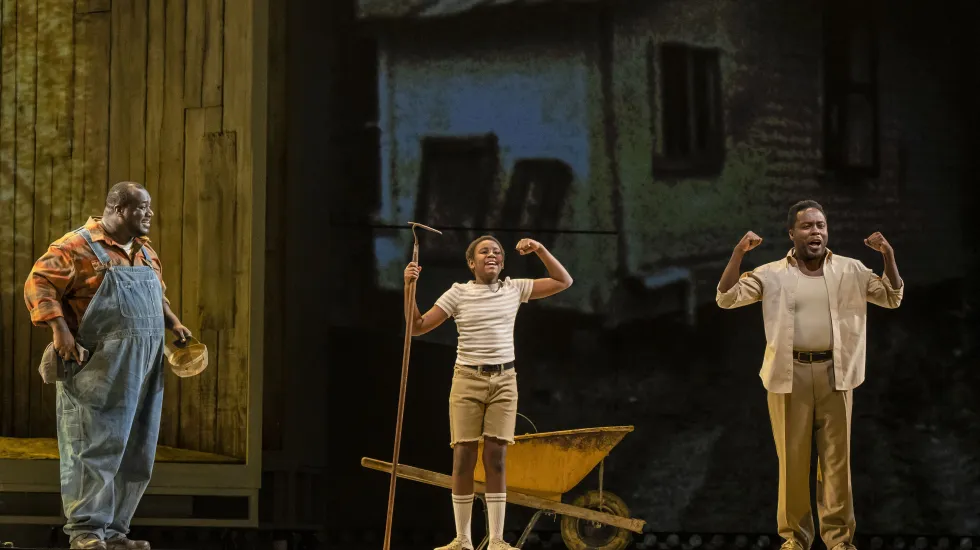

Baritone Will Liverman rises to the vocal and dramatic challenges of the central role of Charles, capturing both the deep pain and quiet toughness of this character and adroitly handling Blanchard’s taut vocal writing.

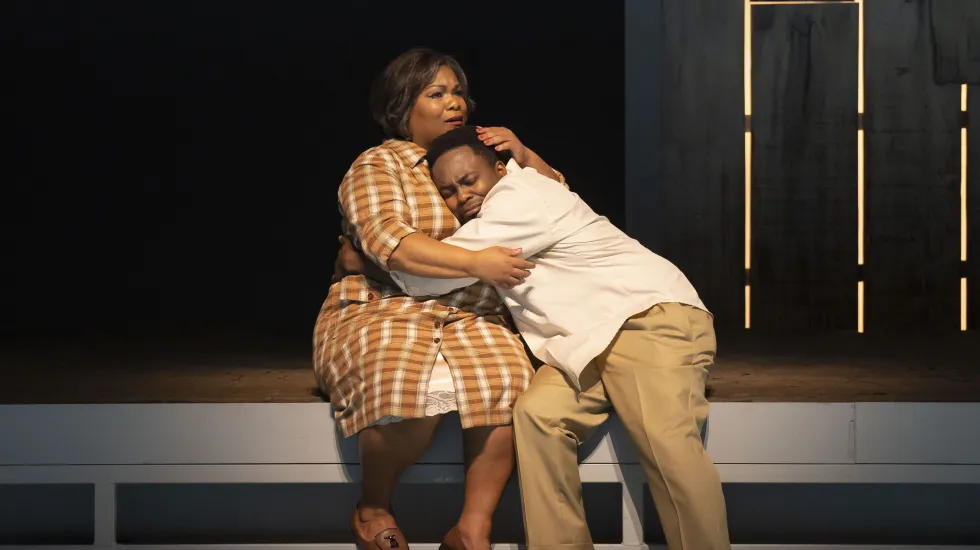

But as obviously central to this opera as Charles is, much of the story’s emotional heart lies with Billie, his mother, who dominates Act 1. In her Lyric debut, soprano Latonia Moore commands the stage with sure-footed technique, spot-on high notes and nuanced vocal shadings, conveying both Billie’s unstoppable force and poignant disappointments.

Other standouts include Reginald Smith Jr., who makes the most of the minor role of Uncle Paul, with his big, enveloping baritone voice, and tenor Chauncey Packer as Spinner, Billie’s smarmy, two-timing husband.

Opera is a challenging medium because of its collaborative and theatrical nature, but Blanchard, whose Academy Award-nominated compositions were clearly a help, is right at home in this realm.

Steering clear of any avant-garde trappings, he has created a score with depth, complexity and richness. The music, which can be breezy, edgy and tough, is decidedly tonal and classical with a jazz-tinged flair and dashes of gospel and blues along the way.

Blanchard’s most ingenious idea is inserting a kind of jazz quartet into the augmented pit orchestra of nearly 60 musicians, with this foursome functioning much like the continuo in baroque repertoire. Particularly notable is the lively, free-flowing playing of pianist Stu Mindeman and the work of Jeff “Tain” Watts on drum set.

Conductor Daniela Candillari nicely shapes the dramatic flow and emotional contours of this opera and capably handles the changing moods and idiomatic flavor of the music.

Does “Fire” have what it takes to endure? It’s too soon to know. But this is a major, compelling work by one of the most important, new composing voices in opera.