It was an otherwise normal week in April, 2013, when a local resident of the western Victorian town of Natimuk observed a strange balloon floating in the skies, and rang the local paper.

"He said the hot-air balloon, shaped like a fish or a parrot with several breasts on each side, rose and continued on without landing," the Wimmera Mail-Times reported.

The origin of the skybourne beast remained a mystery, until a staff member at the newspaper mentioned the spectacle to a mate at The Canberra Times, and its origin suddenly became clear.

It could only have been the much-vaunted hot air balloon that had been commissioned for Canberra's centenary celebrations, but kept diligently under wraps. The organisers were giving the creature - its official name, Skywhale, was not yet known - a practice flight over Natimuk Lake and by the Grampians in preparation for its unveiling on May 9.

They didn't bank on the fact that Australia, with its vast skies so suited to hot-air balloons, is really pretty small in the scheme of things. Before too long, we had got hold of the pictures and published them ourselves ahead of the launch. The embargo had never mentioned the possibility of pre-published photographs in a whole other state.

And so, the Skywhale had a bit of a rocky start, in terms of public relations. When the work was finally officially unveiled with great fanfare on May 9, 2013, Canberrans were less than impressed. This work that had been so protected now arrived with no context.

Sure, its creator, the renowned sculptor Patricia Piccinini was born and raised in Canberra. And yes, the capital ran a popular hot-air balloon festival each autumn, taking advantage of our wide, blue skies, but there the associations ended.

Canberrans, not surprisingly, didn't know what to make of this signature artwork, this so-called high point of our centenary year. Measuring 34 metres from nose to tail, it was, essentially, a many-breasted beast that didn't quite resemble anything. A fish? A parrot? A tortoise, an owl or a whale, perhaps if you squint? And how did it seem so weighed down by those 10 heavy breasts, while simultaneously so graceful and majestic when airborne? Strangely beautiful? Yes. Fantastically absurd? Most definitely. Just the thing to represent the 100th birthday of the national capital, this city of which we were trying to be so damn proud? No. Just ... no.

The initial shock of the reveal had barely worn off when talk turned to the cost of the work - $170,000, at first, then, when the contract with the ballooning company and the piloting and the website and all those other pesky things were added up, it was actually more like $338,000.

The centenary team quickly turned defensive. Robyn Archer, the centenary's creative director and a doyenne of the cabaret scene, described it as a knee-jerk reaction, and seemed at the same time, to be suggesting that Canberrans just weren't sophisticated enough to understand the work.

Piccinini was and is, after all, an artist known for challenging works - sculptures that are hyper-real and other-worldly, lifelike human figures entangled with fantastical, often grotesque creatures. She had fulfilled her brief fair and square, but rather than taking Canberrans along for the ride, the centenary organisers had merely plonked us down in the middle of a strange land, where, they reasoned, no one would possibly consider sniggering at all those teats and hot air.

'Arrogant and self-indulgent'

Meanwhile, on an island more than 5000km north-west of Canberra, Jon Stanhope was fuming.

Canberra's former chief minister was now two years out of office, and trying to live a peaceful life post-politics as the administrator of Christmas Island. But when he saw the initial coverage of the Skywhale reveal, he was dismayed.

He didn't have to wait long before The Canberra Times came calling, keen to know what he thought of what we were now calling a debacle.

And he wasted no time in telling us.

Skywhale, he said, had embarrassed the ACT government, damaged Canberra's image and given fuel to Canberra-bashers for years to come.

Yes, he had been the one to commission the work in the first place, but he had left office by the time the design was unveiled.

And had he been around at the time, he says, he would not have signed off on it.

"I don't think I would, for the very reason of the controversy that it elicited, the division that it's created, the fact that it's actually fed this insatiable national Canberra-bashing that we suffer, and in the centenary year," he said at the time.

If it were still up to him, he said, he would have commissioned a bronze sculpture of Walter and Marion Griffin, and stuck it on Capital Hill.

Instead, the undeniable truth that while the centenary was supposed to be about selling Canberra to the rest of Australia as a real and liveable city, it would instead be symbolised by "a giant tortoise shape with pendulous breasts".

These fighting words would become immortal.

A decade on

It's ironic that one of the main complaints about Skywhale when it was first unveiled was that it was, at the end of the day, an ephemeral creation that didn't even really belong to Canberra at all.

But it was Katy Gallagher, the chief minister at the time, who summed it up best, when she said her "eyes nearly fell out" of her head when she first saw the balloon's design. But it had grown on her. It's a sentiment shared by many over the years; like the city of Canberra itself, the beautiful beast doesn't really take that long to grow on people. (Now federal Finance Minister in the middle of a fraught sitting week, Gallagher was not available for comment).

After the initial shock had faded, it was clear that the work was a technical marvel, strangely life-affirming to observe in full-flight, and all the better if you had the chance to watch it being inflated, to see those strange mammaries fill with air and take to the skies.

She - it's not hard to anthropomorphise something with so much personality - draws sizeable crowds for every outing - in various parts of Australia, as well as the Trans Art Tokyo festival, Ireland's Galway Arts Festival, and in the Brazilian cities of Sao Paulo and Rio De Janeiro.

All told, she probably hasn't flown in the capital more than a dozen times, and yet she has spawned a panoply of merchandise, her image adorning earrings, key rings and socks. Canberra brewery BentSpoke created a Skywhale Ale and, most importantly, the National Gallery of Australia officially acquired the work in 2019, thanks to a private donation. It also commissioned a follow-up work, a companion creature to fly alongside the original. Piccinini, rising to the challenge, created Skywhalepapa, a male version with actual baby creatures hanging off him, instead of breasts.

Musician Jess Green wrote a song to mark the launch, and the Alice Springs based GUTS Dance Central Australia created a dance to go with it.

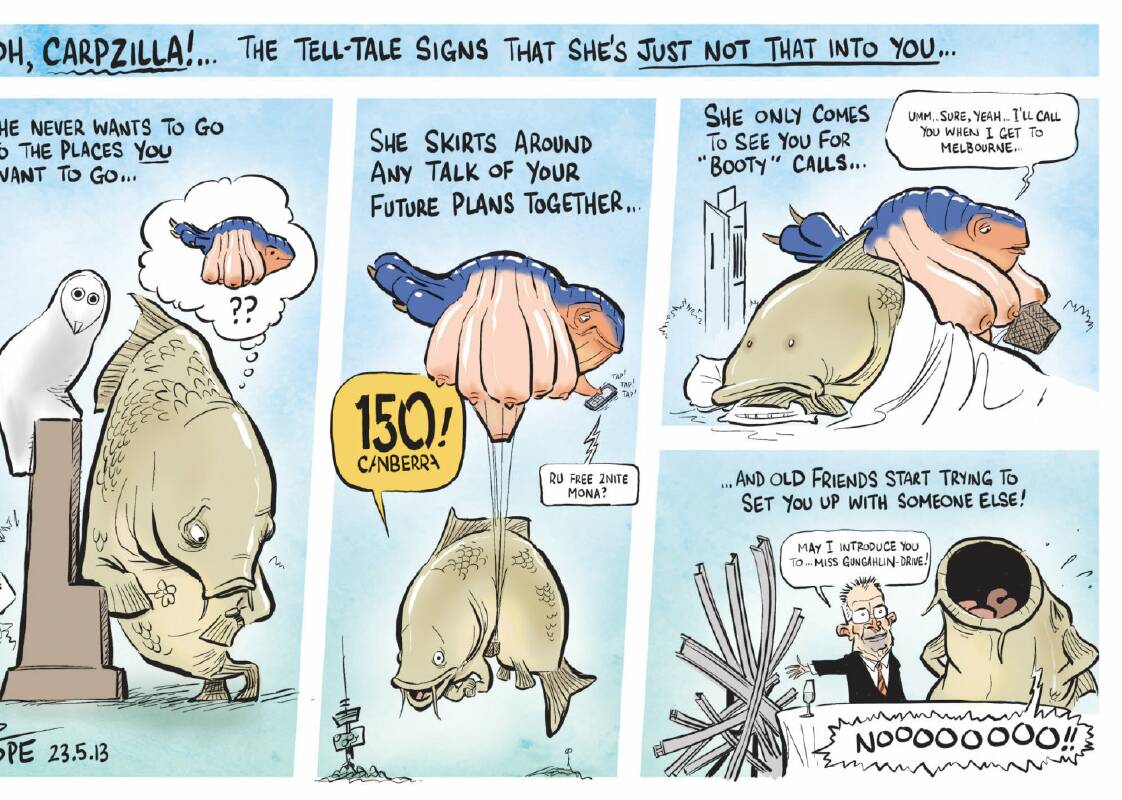

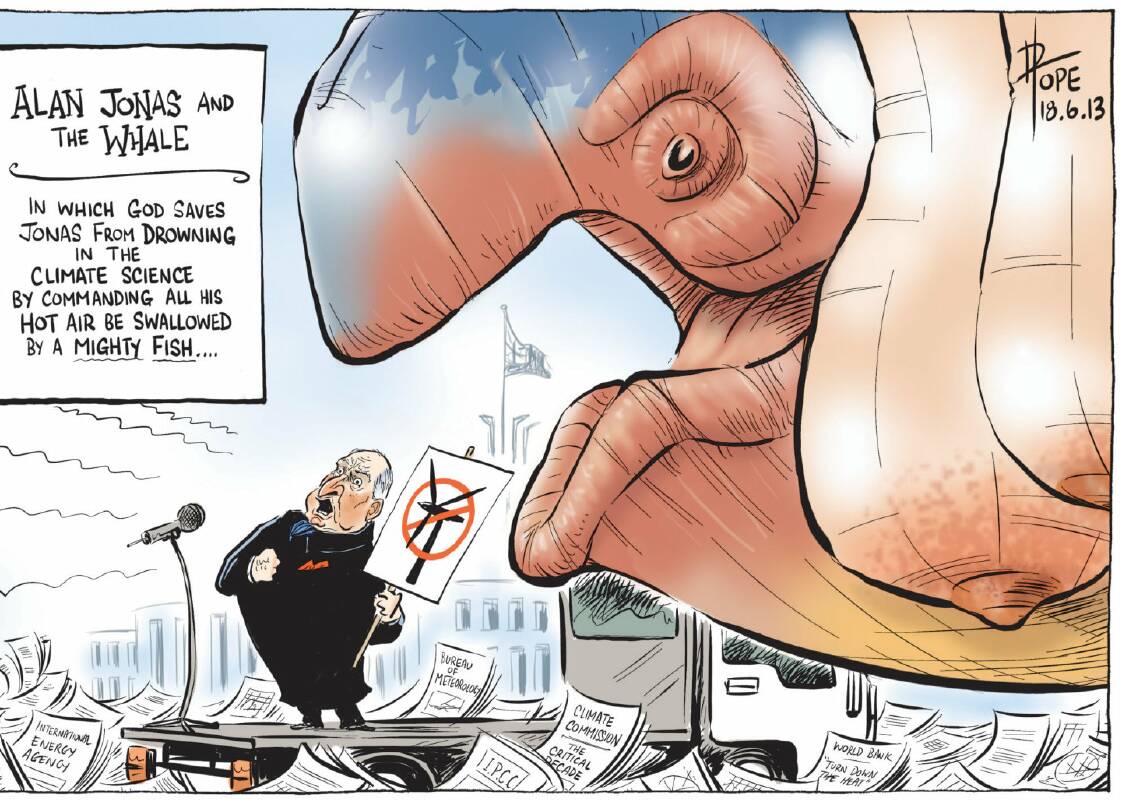

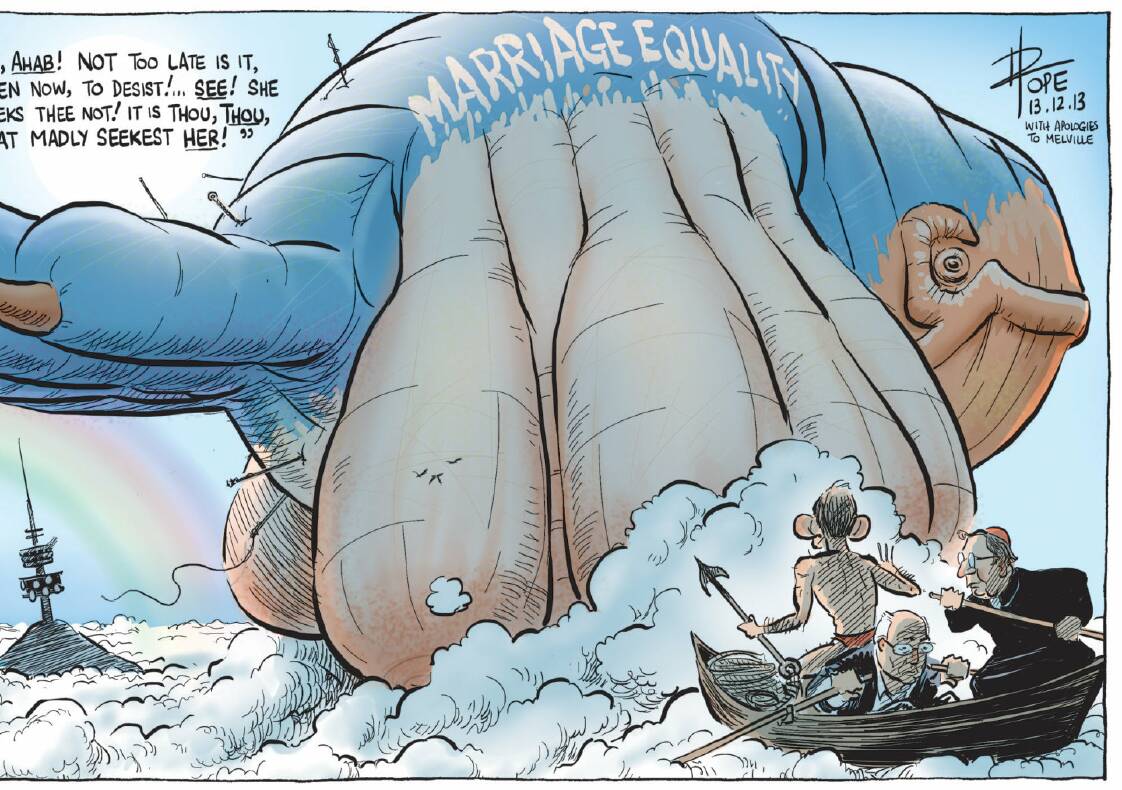

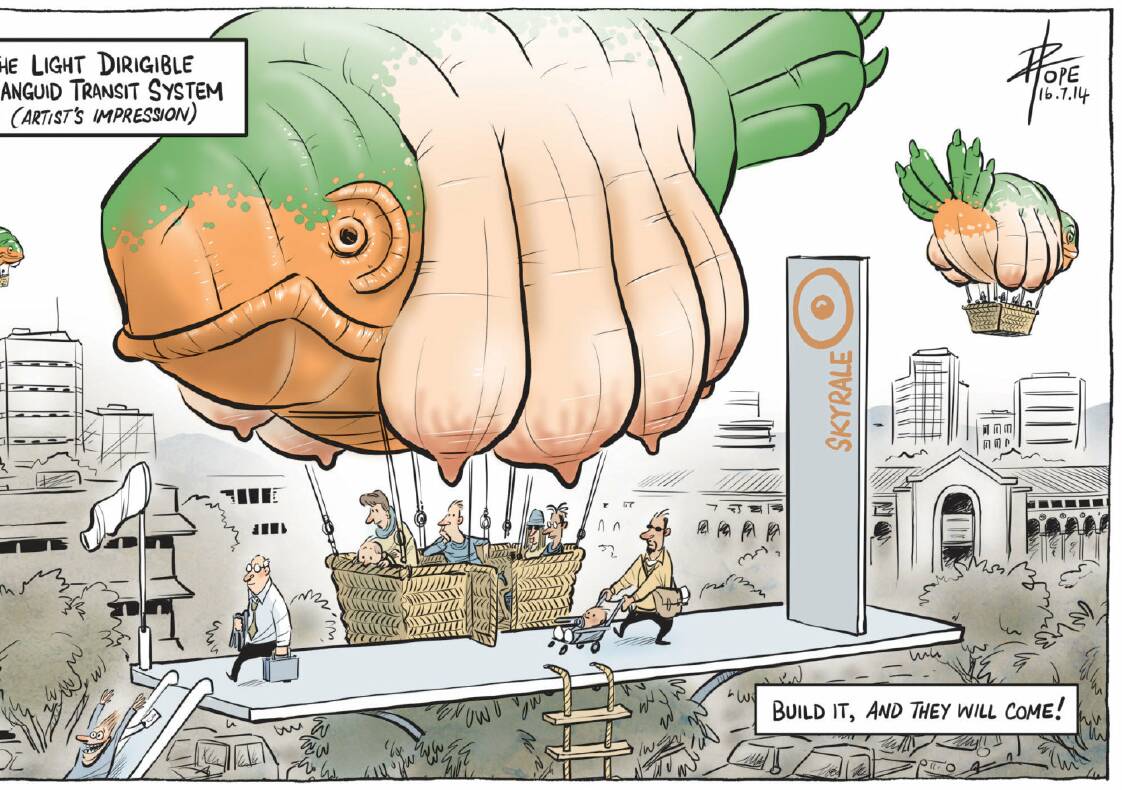

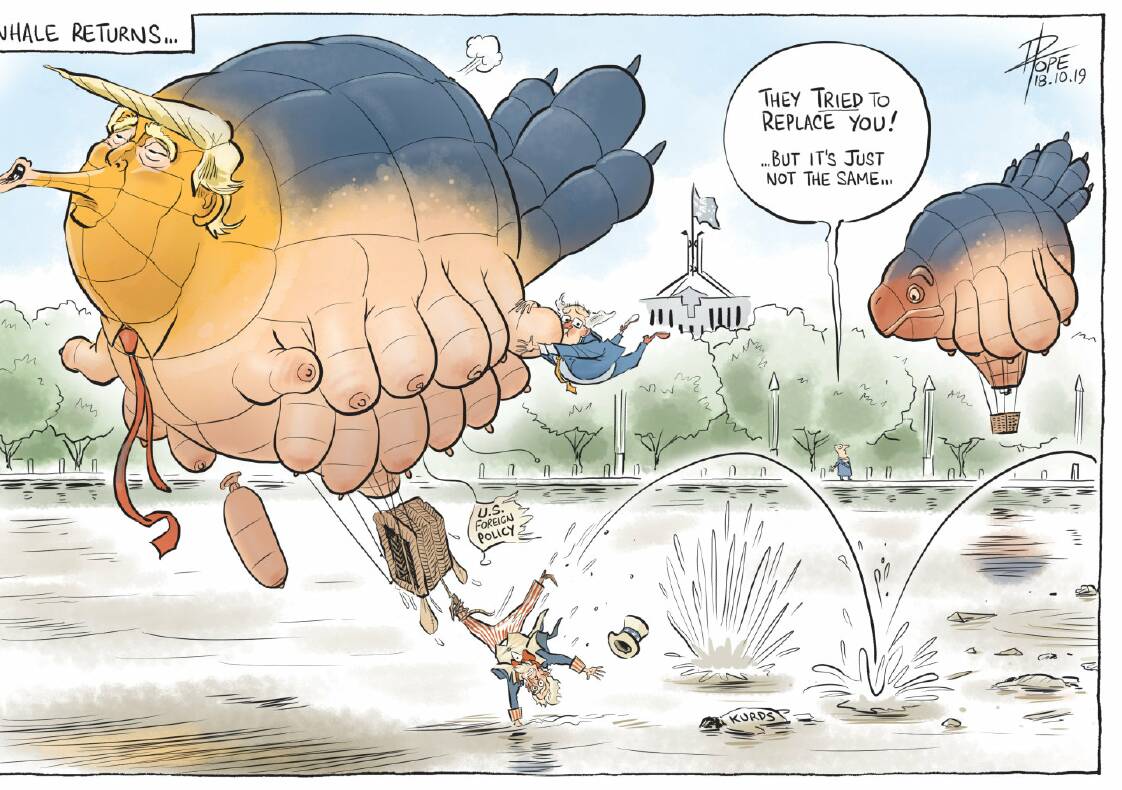

And above all else, she has become a cultural symbol of Canberra in a way we never could have envisaged back in 2013. Kooky, distinctive, instantly recognisable ... and ours. Canberra Times cartoonist David Pope recognised early on the balloon's potential as a kind of shorthand for all kinds of things - whimsy, metaphorical weather, public transport, political gormlessness, all-seeing wisdom. She has appeared over the years in his cartoons and always conveys a message in a way a lesser-known symbol of Canberra never could.

Stanhope has even mellowed over the years, and professes to have forgotten most of what he blasted down the phone at this Canberra Times reporter 10 years ago.

"Skywhale is not not something I dwell on," he said this week.

"I personally think it's, you know, quirkily beautiful. I'm not sure that I've actually embraced it ... But I have no objection to Skywhale, I think it's a wonderful addition to our art collection. And I also acknowledge the significance of the fact that the gallery has taken custodianship and ownership and I think that speaks volumes for its artistic merit."

Just this week, the first statue of a woman - two women, actually, Dame Dorothy Tangney and Dame Enid Lyons - was installed in the Parliamentary Triangle. This could have happened 10 years ago if a statue of Walter and Marion Griffin had been commissioned. But it wasn't, and still hasn't been.

Stanhope chuckles at the irony. But he can't help remembering how symbolic it felt, to see Skywhale unveiled and then, predictably, universally mocked.

"My concern was that in the context of the celebration by we Canberrans of the centenary of our city, a place that we call home, a place that we love, it was unfortunate that one aspect of that celebration divided rather than drew us together," he says.

"I stand by that concern, but that's now in the past. That's old, we've moved on from there. And I must say, I think I would have to accept that Canberra as a whole has fallen in love with Skywhale."

But in fact, the wound cuts deeper than just the mocking world headlines and inevitable, dreary puns. As chief minister, Stanhope had fought a bruising - and ultimately losing - battle in support of public art.

Under his percentage-for-art scheme, which lasted just two years (2007-2009), one per cent of the territory's capital works program each year was devoted to public art. It was something Stanhope once hoped Canberrans would embrace. But they didn't embrace it, they openly and violently objected to it, so much so that he eventually scrapped the scheme.

The last work commissioned under his watch, an unintentionally phallic owl sculpture in Belconnen, was installed just months before Stanhope left office in 2011.

And so this grand unveiling of something so destined for division was a bitter pill to swallow, even from as far away as Christmas Island.

"After the cancellation of that scheme, because it was so stridently opposed by so many Canberrans, to then produce as part of the celebration of our centenary a work of art seemed to me to fly in the face of that bit of uncomfortable history," he says.

It's 12 years since he left office, and he still has "moments of enormous regret" that he discontinued public art, although the National Arboretum Canberra, a project he initiated and persisted with in face of strident opposition, is today admired and loved.

"The memory that it raises for me is that Skywhale is the last significant piece of public art commissioned by the ACT government," he says.

"And for 10 years, in the whole of the last decade, since the commissioning of the Skywhale, the ACT government has not commissioned a single significant piece of art."

Perhaps this is part of the reason for our slow-growing acceptance - even love - for our curious symbol.

Rising to the occasion

Patricia Piccinini, for one, isn't remotely surprised at the longevity of her creation. She has spoken before about her hurt and confusion at the initial reaction to her work but, like the beast herself, she has risen to the occasion, and never misses an opportunity to talk about its origins, and how much she enjoys seeing her in the skies.

The centenary team could have done far worse than allow Piccinini herself to talk us through it before the unveiling - to explain her thoughts on the environment, and her fascination with weird creatures.

And, for a work that is essentially about evolution, it has also been part of a kind of psychic evolution on the part of the people she so wanted to delight back in the centenary year.

"The work is really about how these small mammals went back into the sea and became these gigantic sea-dwelling creatures, even though it was a really difficult space for them to live in," she says, over the phone from Rotterdam. She is there to stage a major exhibition of her work at the Kunsthal, a contemporary art gallery, not that we need reminding of her considerable clout as an artist.

"Isn't it amazing that evolution can pull off these incredible adaptations, and we're just lucky to be here? [T]hat's what the work is about. It's about evolution and the wonder of it.

"But it has also had its own evolution, from, at the beginning, people being slightly suspicious and averse to it because they've gone oh, it's only a balloon, it pops and it's over. And then in the psyche, in the hearts of people, it's evolved into something from aversion to, I think, care."

She says it has also affirmed for her the power of art - something she has never really doubted, even though she's had her own reckonings with it over the years. Like many artists, she can spend hours, days, even weeks toiling away in her studio, away from the outside world. It's instructive, and revitalising, she says, to emerge and see how people respond to the work that's already out there.

"When I left art school and I ran an artist-run space, we would have exhibitions and, like, 150 people would turn up, out of a five million-person city," she says.

"I just thought, is art just for these small groups of people? And how can I be part of the everyday life of people? Because that's culture - that's how you build meaning into our lives.

"And so I've learnt that it is possible, and also not to underestimate people. I think it was a challenging work, and people have risen to it. They haven't just dismissed it and thought, it's ridiculous, it's indulgent ...They've thought no, there is an idea here. I can connect with it.

"Art can do that. It doesn't often happen, but it can happen."

- The next flight of Skywhale and Skywhalepapa will be on May 6 at Tamworth Regional Gallery.

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.