Tardigrades, the ubiquitous microscopic animals that resemble gummy bears with eight legs, are renowned for their ability to survive some of the harshest environmental conditions for decades without food and water.

These hardy animals can easily endure levels of radiation that would be lethal to most other forms of life, extreme temperatures and even survive in the vacuum of space. Some scientists think that uncovering the genes responsible for their remarkable resilience, particularly to ultrahigh radiation, could unlock a range of potential applications from cancer research to space exploration.

And we may be closer than ever to unlocking them. Chinese scientists have now identified a new species of tardigrades hosting thousands of genes that become more active when exposed to radiation. The findings point to a complex defense system that shields tardigrade DNA from radiation-induced damage and can pave the way for devising better protection for astronauts from the stresses of long-duration missions, researchers say.

The new species, named Hypsibius henanensis after China's Henan province where it was collected about six years ago, was pummeled with doses of radiation many times higher than what would be lethal for humans. The bombardment affected 2,801 tardigrade genes associated with DNA repair, cell division, hormone metabolism and immune responses, according to a paper published Oct. 25 in the journal Science.

Related: These tiny indestructible tardigrades will reveal how to survive in extremes of space

One of the genes that became most active, called DODA1, appears to resist radiation damage by enabling tardigrades to produce antioxidant pigments known as betalains, which can erase some of the harmful reactive chemicals inside cells that are caused by radiation. When the researchers treated human cells with a tardigrade's betalains, they found the cells fared much better at surviving radiation than untreated cells, study co-author Lingqiang Zhang, who is a molecular and cellular biologist at the Beijing Institute of Lifeomics, told Nature News.

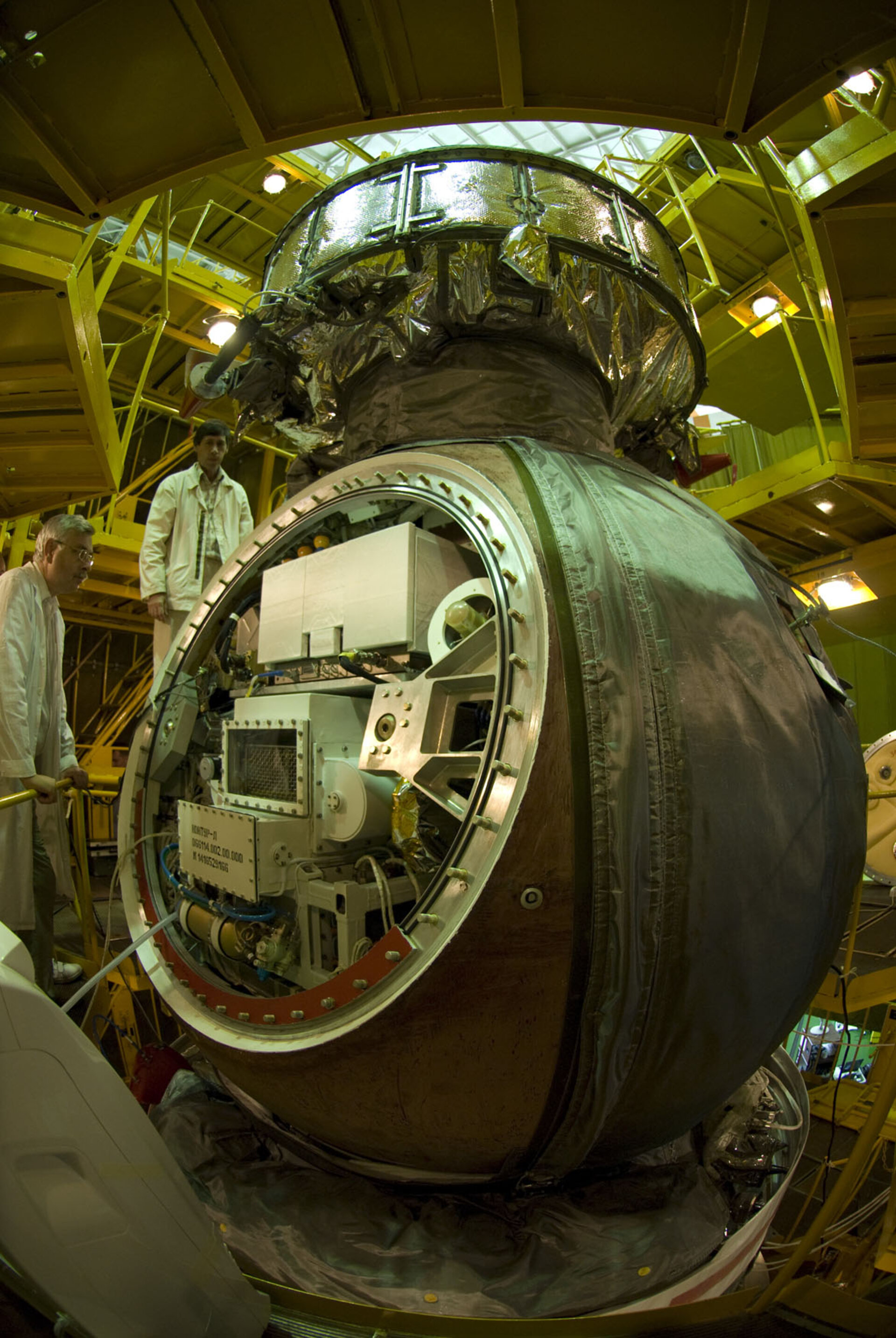

Tardigrades, commonly known as water bears or moss piglets, have been the subject of extensive research due to their extraordinary resilience. In 2007, they became the first animals to survive exposure to outer space after a Russian crewless capsule ferried 3,000 living tardigrades on a European mission to low Earth orbit, and exposed them to the hard vacuum of space for 10 days. 68 percent of them survived and gave birth to normal offspring. The same occurred with tardigrades that were blasted to space in 2011 on the final flight of NASA's space shuttle Endeavour.

A few thousand tardigrades were spilled onto the moon's surface after riding there aboard Israel's Beresheet spacecraft, which crashed during landing. While the fact that the specimens lay dormant on lunar soil raised ethical questions, microbiologists have deemed their chances of colonizing the moon zero, given the lack of oxygen and liquid water.

Tardigrades' most recent trip to space was in 2021 to the International Space Station, where a long-term study of their genes and other survival techniques is underway.

"We want to see what 'tricks' they use to survive when they arrive in space, and, over time, what tricks their offspring use," Thomas Boothby, an associate professor of molecular biology at the University of Wyoming, said in a previous NASA statement. "Are they the same or do they change across generations? We just don't know what to expect."

Scientists know from previous research that tardigrades persist through unfavorable conditions by rapidly suspending their metabolism, for which they lose majority of their body water and shrink to half their normal sizes, a state known as cryptobiosis. After returning from space, they regained their former vigor within just 30 minutes of becoming hydrated.

The tiny creatures are also likely capable of producing heaps of antioxidants — such as the newfound reservoir of betalains — to combat harmful, radiation-induced changes in their bodies, scientists say.

"We have seen them do this in response to radiation on Earth," said Boothby. "We think the ways tardigrades have evolved to withstand extreme environments on this planet may also be what protects them against the stresses of spaceflight."