There’s something apt about celebrating the anniversary of Ted Hughes’s death with the republication of Lupercal, which includes such Hughes classics as “Pike” and “Hawk Roosting”. Today, more than ever, Hughes – who died 25 years ago this Sunday – has become a voice for our times, taking his readers into a closer intimacy with nature.

In a blink, it’s 1960: nature’s unclouded by climate change, and it’s an age of innocence in which JFK is about to become president; another American, TS Eliot, is a director at Faber & Faber; and Samuel Beckett has just published Happy Days. Hughes is in the fourth year of his marriage, and his beloved wife will open this airy, slim volume of some 40 poems (notably “A Woman Unconscious” and “An Otter”) to devour its carefree dedication, “To Sylvia”.

With this publication, Ted’s voice is coming of age with many others. After a khaki decade of rationing, toad in the hole and national service, England’s war babies are coming out to play, finding a language to infuriate their elders. The tight-lipped veterans of Normandy and El Alamein, who have known nothing but the rhetoric of sacrifice and stoicism, are not ready for this. In the year of Lupercal, Brenda Lee’s “I Want To Be Wanted” vied for a top ten slot with Chubby Checker and “The Twist”. Strong feelings were all the rage.

Sylvia Plath is all about strong feelings. She’s a force of nature who recognises her equal in Hughes. Famously, she drew blood the night they met. In 1960, the Daddy-hating graduate of Vassar is still in her husband’s shadow. Two years her senior, he’s more established, having already published The Hawk in the Rain (1957). Sylvia, with her wide smile, earnest intentions and auburn-gold hair, looks like an American student; Ted, by contrast, could pass for a gamekeeper. He would appear in Faber’s offices in country boots and that kind of all-seasons jacket whose deep pockets might conceal a trout or a dead rabbit. One editor remembers opening a bag with a Hughes manuscript and being overpowered by the stink of fish.

His distinctive gift as a poet was the psychic shock he’d distilled into Lupercal, a visceral response to the riotous and savage affrays of the natural world. This collection, reaching into myth and folklore, is vintage Hughes. The Roman god Lupercus is better known as Pan. Lupercal, celebrated annually on 15 February, was the festival of purification and fertility, favourite subjects of Plath and Hughes.

The poet and critic Al Alvarez, who was close to Sylvia, was among the first to recognise the genius of this remarkable couple. Reviewing Lupercal in The Observer, Alvarez wrote: “Hughes has found his own voice, created his own artistic world and has emerged as a poet of the first importance ... What Ted Hughes has done is to take a limited, personal theme and, by an act of immensely assured poetic skill, has broadened it until it seems to touch upon nearly everything that concerns us.”

Ted and Sylvia were both in the antechamber to greatness. Hughes had found his voice as a poet. Plath, more troubled, was still a work in progress. Her forthcoming novel, The Bell Jar, was the “apprentice work” she believed she had to write “to free myself from the past”. In February 1963, in one blind, savage moment of self-destruction, she became the goddess of a doomed future that would translate into their tormented, joint posterity.

Across the water in Belfast, a younger poet read the reviews of Lupercal and hunted down a copy in his local library. Years later, in 1979, still new to Faber, Seamus Heaney wrote Hughes a fan letter. “Since I opened Lupercal in the Belfast Public Library in November 1962, the lifeline to Hughesville has been in its emergent differing ways a confirmation.”

The Hughes I knew was always at one with the masters of the pastoral tradition such as Heaney. Anyone who wrote as he did, at eye level with field and stream, was his partner in the all-important job of being a poet. English literature, in Ted’s presence, was this living organism, whose thrilling sinews were as real to him as flesh and blood. In conversation, I remember, Ted used to echo WH Auden, another Faber poet, and speak of literature as a constant process of “communing with the dead”.

There’s rarely been a writer who quarried so much of his life and work from our folklore, especially rare dialect words. He would speak about this wellspring of inspiration as a tangible phenomenon created by his ancestors, or – as he put it to The Paris Review in 1995 – his “sacred canon”, the illustrious dead who spoke to him like living relatives: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Marlowe, Blake, Wordsworth, Keats, Coleridge, Hopkins, Yeats and Eliot.

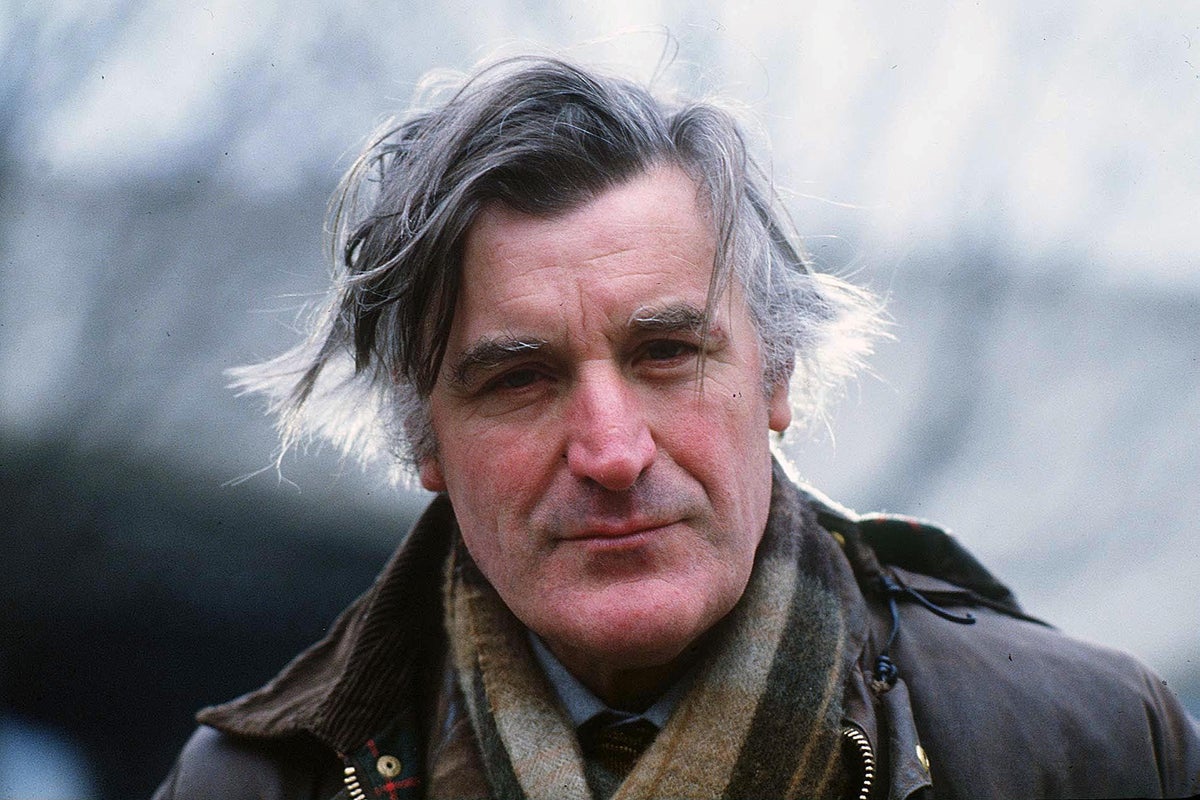

Ted Hughes photographed at a party in 1970— (Getty)

There was nothing contrived about this association. Such poets were his raison d’etre; the fellow artists to whom he would always be drawn, as a moth to a flame. The fire that inspired Hughes the artist was never less than a pure and incandescent light, guiding everything he wrote. Yes, he was often linked with the Romantics – he and Wordsworth have a lot in common – but there was one writer with whom, as I came to know him better, he was particularly obsessed: the William Shakespeare whose Complete Works became his secular Bible.

Indeed, in his most quasi-psychic moods – which were never less than speculative and playful – he would turn to Shakespeare for comfort in that inner dialogue with his troubled soul. If this sounds far-fetched, we have Hughes’s own witness to Shakespeare’s hold over his artistic wellbeing, even his very existence. In 1998, during his protracted final illness, Hughes confessed to a friend that he believed his lifelong fixation with Shakespeare had become almost fatal.

Hughes had first begun to read and re-read The Complete Works during his undergraduate years at Pembroke College, Cambridge. In 1952, he described this routine to his sister Olwyn: “I get up at 6, and read a Shakespeare play before 9 ... that early bout puts me ahead all day.” The spell cast over him by Shakespeare, central to these university days, predates his tumultuous meeting with Plath. Once she had burst into his life in 1956, she was swiftly drawn into Ted’s Shakespearean landscape, rooted in the natural world and illuminated by lightning flashes of magic and the supernatural.

To me, they are Oberon and Titania. There are lines in A Midsummer Night’s Dream that conjure their fiery spirits and an adoration of that English natural world still unblemished by phosphates or global warming. By the winter of 1963, Ted and Sylvia – the latter whom of course I never knew – were selfish and fearless erotomanes, squabbling lovers who would eventually turn their fairy world into a hellscape.

I don’t want ever to be forgiven. I don’t mean that I shall become a public shrine of mourning and remorse. But if there is an eternity, I am damned in it— Ted Hughes

At the turn of that year, the winter weather, which I remember vividly as a child, was brutal. Snow falling on Boxing Day, thick and heavy, made travel impossible. By New Year, the country was paralysed. Water pipes froze, with many power cuts. Candles ran short, while the cold went on and on, a merciless offensive pushing everyone to the limit.

Hughes had recently left his wife for another woman. Plath, having taken a flat in Fitzroy Road, Camden Town, was “living like a Spartan”, completing the Ariel poems that made her famous. The Bell Jar – which tells us what madness felt like to Plath – was about to be published under the name of “Victoria Lucas”.

For a better insight into Plath’s breakdown, her letters (and Ted’s) give us all we need to know about the terrible events of 11 February 1963, the day she gassed herself “at about 6 am” with her children Frieda and Nick asleep next door. A month later, Hughes wrote to Sylvia’s mother, “I don’t want ever to be forgiven. I don’t mean that I shall become a public shrine of mourning and remorse. But if there is an eternity, I am damned in it. Sylvia was one of the greatest truest spirits alive, and in her last months she became a great poet.” Smothered in grief, Hughes compared her to Emily Dickinson.

Ted Hughes on the first day of the trout fishing season at Wistlandpound, Devon, 1 April 1986— (Nick Rogers/Shutterstock)

His fateful struggles with Plath’s memory took many forms. None became stranger than his writings on Shakespeare, “the tragic equation” in which the woman he saw as his love goddess became demonised as the “Queen of Hell”. But then he suffered another, even more dreadful loss. His lover Assia Wevill’s death pact also took their four-year-old daughter, Shura.

While Crow (1966-69) became the volume that echoed these terrible years, Shakespeare remained his principal consolation. By the 1970s, Hughes’ obsessive re-reading of The First Folio had translated the “great equation” into an algebraic certainty. In 1990, this morphed into his magnum opus, a feral typescript titled Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being.

The Ted Hughes I remember had been appointed poet laureate in 1984, but there was no whiff of the establishment about his presence in Faber’s Queen Square offices. Quite the reverse. It was rumoured that Her Majesty fancied her laureate. Audiences with him, often overrunning, were devoted to horses and dogs.

His editor, Christopher Reid, who masterminded a classic edition of Hughes’s Letters, paints a vivid picture of the poet-correspondent that conveys what it was like to be in his company: “invariably direct and businesslike, with an extra ingredient of confidentiality and candour ... So much more concentration, force, immediacy, grace and wit ... The word that perhaps best suited [him] was ‘generous’. Here was a writer who, even on the most ordinary occasions, could not ... give anything short of his best performance.” Who can forget that voice, so intimate and timeless? To remember Hughes speaking is to be spellbound again by the caressing Yorkshire tenor of a great poet.

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes on their honeymoon, Paris, 1956— (Everett/Shutterstock)

On his visits to Queen Square, in his farmer’s rig, Hughes always brought the English landscape and its way of life into the office, a place he fitted into with ease. Faber and Faber in the 1980s was an odd mixture of a church and a girls’ school. Many of the staff were under 40, and some of them were still in their twenties. The atmosphere was sleepless, youthful and frenetic. I think Hughes enjoyed the vibe (so different from the Eliot days), notably the atmosphere of young people doing everything for the first time. He was part of “Ted & Sylvia”, a figure of myth, but we treated him as one of us.

By now Hughes and Plath had become yoked together in the tragic psychodrama of their marriage. Together with Plath’s Journals, there was a highly contentious catalogue of biographical studies (The Silent Woman; Bitter Fame; The Haunting of Sylvia Plath; Method and Madness; Rough Magic; The Death and Life of Sylvia Plath). If you worked at Faber, as I did, during the late Seventies and Eighties, the Hughes of the headlines was never visible. He was always the in-house poet, mentor, and friend.

When he was in the house, it became his home. We, his dysfunctional family, took everything, and especially our luck, for granted. Amid a hurricane of aesthetic and cultural change, Ted was a moral and artistic compass. A regular contributor at sales conferences, he would confide his belief in astrology, and we would invite him to be our guest. He reciprocated by writing “An Ode to the Organism” (1994):

Like Sisyphus successful with his boulder

The author scales his Alp of manuscript ...

Throughout the Eighties and Nineties, Hughes grappled with his Alp, Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being. Nothing spoke more eloquently about his commitment to his life as an artist than his dedication to this extraordinary project. It was Hughes’s conviction that, in unlocking the “secret” to Shakespeare’s work, he would reconcile the war inside himself in the aftermath of Plath’s suicide. “I was fiercely bitten by my Hypothesis Bug,” he wrote, “and could not not do it.”

This “bug” – eventually a full-blown fever – was Hughes’s belief that, throughout 14 plays, culminating in The Tempest, Shakespeare was “hammering” at a “great equation” in which the playwright “presented the mystery of himself to himself”. Most poets, Hughes declared, “never come anywhere near divining the master-plan of their whole make-up”. If he followed Shakespeare, perhaps he could achieve a psychic reconciliation.

Hughes in 1970— (Getty)

At Queen Square, I recall, there was nothing but the highest optimism about a new book on Shakespeare by the poet laureate – a subject on which Hughes, in conversation, was never less than bewitching, especially on Shakespeare’s language. What could possibly go wrong?

The documents in the Faber archive, however, show Hughes fighting with drafts of this manuscript as if with demons. As well as plucking out “Shakespeare’s heart”, Hughes saw his new book as a means of redeeming himself vis a vis Plath’s unappeased memory. Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being is like nothing else Hughes ever wrote; an extraordinary one-off that unlocks a window into the soul of a sublime artist: it’s the record of an obsession, a monument of English prose, a would-be cult, an incipient nervous breakdown, and a strange kind of therapeutic autobiography.

On 9 March 1992, Hughes, having consulted his astrological charts as usual, launched his magnum opus, but the music of the spheres became a hideous cacophony. The Independent declared the book “egregious twaddle”, which was by no means the worst verdict. The near-universal rejection of his work exacted a fearful toll. Writing to a friend in 1998, shortly before he died, Hughes describes two years of destroying his health, “staying up to 3am and 4am”. Elsewhere, he claims that “writing critical prose actually damaged my immune system”. His Shakespeare book, he says, nearly killed him. He was “not sure I’ve ever got over it”.

Failure and redemption can be twins. Hughes put aside “critical prose”, and returned to his muse. In January 1998, he published Birthday Letters, to heartfelt, national acclaim. Released from his “tragic equation”, he was now writing with a zest and clarity that recalled his finest work. The failure of one project had fuelled his determination to complete the other: “a thing I had always thought unthinkable ... so dead against my near-inborn conviction that you never talk about yourself in this way, in poetry”. He was taking his cue from Shakespeare, the master of reconciling candour with jeopardy, writing in his own voice, not another’s. As Ted Hughes, he spoke, triumphantly, for all time.

Within a year, his funeral was celebrated in Westminster Abbey. I remember Ted’s recorded voice echoing among the shadows of the nave, a spine-tingling moment when life and art, love and Shakespeare came together in his reading from Cymbeline:

Fear no more the heat of the sun

Nor the furious winter’s rages

Thou thy wordly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages...

Posterity is capricious, but I think we knew then that Ted was already passing among the dead with whom he most wished to commune.