In the packed cafeteria of Pugh Elementary School Tuesday evening, Houston Independent School District (HISD) Superintendent Mike Miles worked hard to sell his wholesale campus reform program, called the New Education System (NES), to a resistant crowd, some holding signs that read “Our Children, Our Schools.” Miles boasted that 57 campuses had voluntarily opted into the program.

“They love this,” Miles said. “That’s why teachers at 57 schools volunteered.”

As part of the state’s takeover of HISD—which ousted an elected school board and replaced its leadership with a board of managers and a superintendent handpicked by State Education Commissioner Mike Morath—Miles has previously said that 150 HISD schools would be under the NES by 2025. In March, the Texas Education Agency seized control of HISD, citing past failures to meet state standards at one high school. In addition to the schools that opted in, another 28 were required to participate because the schools are elementary and middle schools with students who “feed into” three high schools with lower accountability ratings.

NES originates from the Third Future Schools, a charter school network Miles founded. It requires teachers to teach from a scripted curriculum. The district will decide campus schedules, staffing, and budgets. Students who are considered disruptive are pulled out of the classroom to attend via Zoom. In addition, Miles has promised teachers support for grading, making copies, small-group instruction, and a stipend of $10,000. Salary schedules for teachers at what he calls “NES-aligned schools,” or those that opted in, will remain the same while teachers at NES-mandated schools receive a salary bump and have to reapply for their jobs. As part of the sweeping changes, last Friday Miles eliminated up to 600 administrative positions from the central office.

Since the Texas Education Agency appointed Miles to lead the school district, he has faced community protests by citizens opposed to the state agency’s takeover. But he has maintained that schools are embracing his changes.

But interviews, email correspondence, and audio recordings of campus meetings that the Texas Observer obtained contradict Miles’ public relations message that there is widespread teacher support for his program. Teachers, parents, and community members from nine of the 57 schools we spoke to said they had no opportunity to weigh in; teachers were threatened with losing their jobs if their campus did not join the program.

“Our hours will change. Our schedules will change. Our curriculum will change. But we have no input in it,” said Michelle Collins, a teacher at DeZavala Elementary School. “Neither do parents.”

According to the state education law, a Shared Decision Making Committee (SDMC) composed of parents, community representatives, teachers, other campus personnel, and a business representative is required to be “involved in decisions in the areas of planning, budgeting, curriculum, staffing patterns, staff development, and school organization.”

While Miles has publicly asked principals to obtain school input, SDMC committee members from five schools in the program confirmed with the Observer that they never met to discuss the issue. SDMC members and teachers from other schools reported that even when they did meet, they did not have a vote in the decision. One teacher said their staff voted not to opt in, but then later saw their school’s name included in the list of 57 schools in the news.

In an audio recording of Wainwright Elementary School’s SDMC meeting held July 10 and shared with the Observer, Principal Michelle Lewis told committee members, “If you’re not willing to dive in and do this with us, then this is not the campus for you.” No teacher representatives attended the meeting.

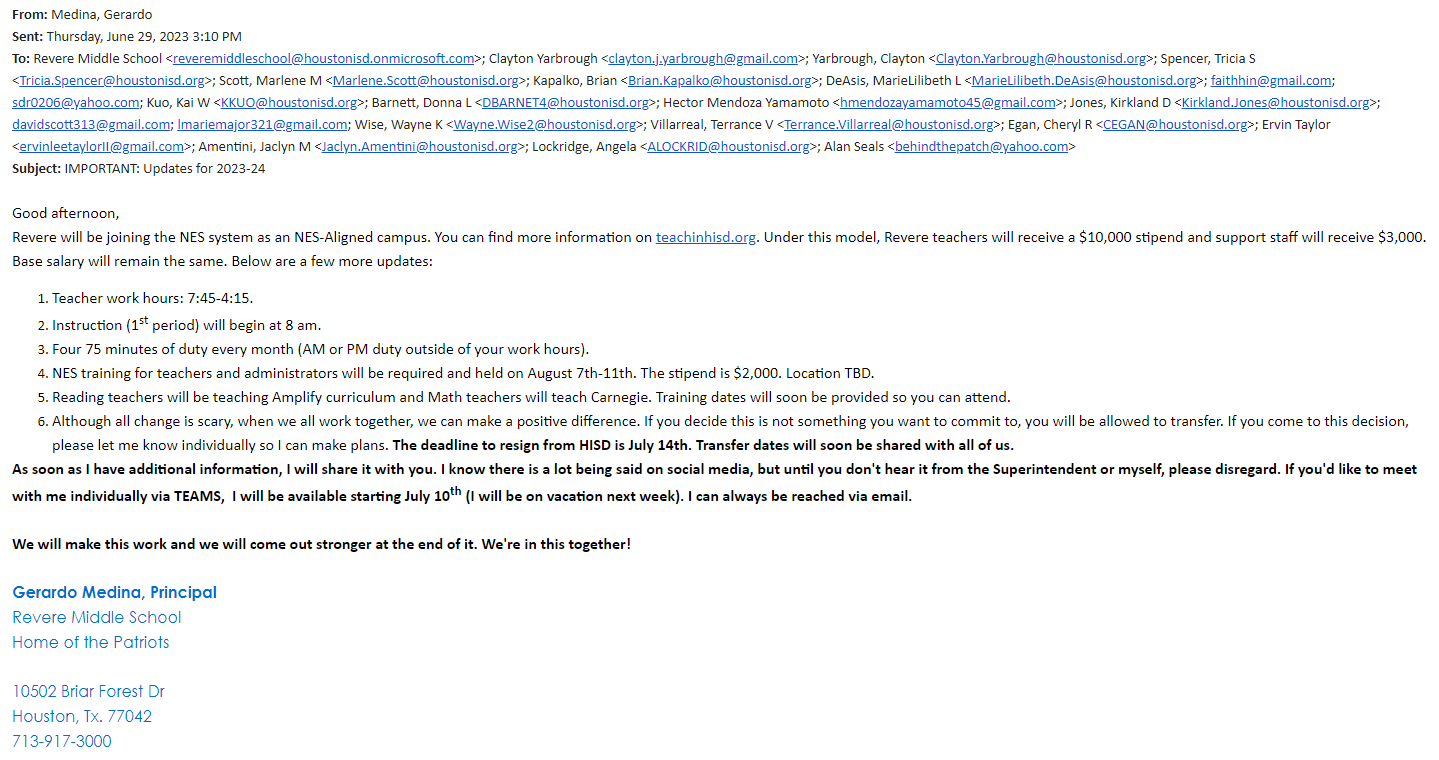

Revere Middle School Principal Gerardo Medina did not consult with the school’s SDMC committee or with teachers. In lieu of discussion, he sent out an email on June 29 to campus employees informing them of his decision to join Miles’ NES-aligned program.

“If you decide this is not something you want to commit to, you will be allowed to transfer,” Medina wrote.

This gave teachers only a few days before this Friday to decide if they want to continue to work within the district. To avoid losing their state teaching certification, they have up to 45 days before the first day of school to withdraw from their contract. Miles, however, has said teachers can continue to transfer within the district after the deadline.

HISD sidestepped parents and teachers’ complaint that they were not included in the decision making, and responded to the Observer via email, saying, “Principals at the 57 NESA schools were asked to consult with their teachers, faculty, and staff prior to opting in and after doing so, were ready to take bold action to improve outcomes for all students and eradicate the persistent achievement and opportunity gaps in the district.”

During campus meetings about Miles’ NES program, teachers raised common concerns: staffing shortages, staffing, and program cuts, longer work hours, and the loss of autonomy to tailor their curriculum to diverse students.

Miles has promised teachers they could focus all their time on instruction. But parents and teachers the Observer spoke to questioned if there were enough teachers, particularly certified teachers who are trained and have accreditation, to fill those positions when the district has struggled to fill vacancies.

“I cannot see how any of that is actually going to come to fruition when you can’t find classroom teachers in a regular situation,” Collins said.

Ellen, a teacher at M.C. Williams Middle School, who requested we use her middle name for fear of retaliation, said her school recently lost five teachers to other NES-mandated schools offering higher salaries. They still have uncertified teachers filling vacant positions.

Elective teachers also expressed concerns about losing their jobs. While Miles has promised that existing magnet and elective programs will not be supplanted by NES’ “dyad program” of uncertified, independent contractors teaching music and art, a school staffing model Miles provided principals shows that the number of elective teacher positions are limited according to the school population. For example, campuses with 450 to 600 students will only have six elective teachers, including P.E. teachers.

Additionally, teachers expressed misgivings about working longer hours—at least 5 hours more per week are required under the program—even with the promise of a $10,000 stipend. Juan Carlos Suarez said his principal at Bonner Elementary did not tell the staff about the longer workday.

“They only gave us the schedules for the kids, which is shorter,” Suarez said. He added that teachers were told students were not to have any downtime. “To not give kids any downtime, for them to be productive every single second, or have any breathing room, it’s like we’re training them to be prisoners.”

Teachers reported feeling pressured by potential job loss to get on board. Echoing what Miles told school principals at a meeting last Thursday, teachers shared that they were told that if any school in their elementary to high school feeder pattern did not meet the state’s standards, then all schools would have to be reconstituted. Like the 28 schools mandated to join Miles’ NES program, campus employees would have to reapply for their jobs the following school year.

“The threat was if you’re not opted in, and your school becomes NES mandated, your faculty has to go through the whole rehiring and interview process all over again,” Collins said.

Wainwright Principal Michelle Lewis said in the audio recording, “We have been promised we do not have to reconstitute. … You gotta buy into what we’re doing to keep the job.”

Parents and teachers we spoke to expressed that, with all the required changes, they felt ill-informed and ill-prepared for the next school year, which begins in six weeks.

“How are we trying to roll this out in August when we can’t answer any questions related to the day-to-day functioning of a building,” Collins said.

Ellen reiterated Collin’s concern: “We have no idea what we’re walking into when those doors open.”