On March 1, 2022, Toby Price, an assistant principal at Gary Road Elementary School in New Byrum, Mississippi, faced a problem. The reader booked for a Zoom session for 240 grade two students hadn’t shown up. So Price grabbed one of his favourite books, I Need a New Butt, and began reading.

He was fired two days later.

In Price’s termination letter, Hinds County Schools Superintendent Delesicia Martin cited “unnecessary embarrassment, a lack of professionalism and impaired judgment” on Price’s part. The superintendent was particularly disturbed by the word “fart”, which he called “inappropriate”.

However, the book, which features a character who sets out to find a replacement bum after he discovers his has a crack in it, is recommended for the same age group as Price’s audience.

Read more: Battles over book bans reflect conflicts from the 1980s

Ban sets a dangerous precedent

Why – apart from depriving young children of entertainment – does this matter? Making decisions about who can access books on the basis of whether they offend the sensibilities of those in authority, rather than whether they’re a good match for their target audience, sets a dangerous precedent.

Conservatives in the United States have recently focused on school boards as easy pressure points in the ongoing culture wars.

Late last year Rabih Abuismail, a member of the Spotsylvania County School Board in Virginia, proposed that books be not only be removed from school libraries, but also burned for good measure. In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis supports a bill (colloquially known as the “Don’t Say Gay Bill”) which has this wording:

Classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.

This joins with some dozens of other bills in state legislatures across the US which seek to repress discussion of gender, race or sexual identity. The terms are deliberately vague so that teachers can never know whether they’re on safe ground.

In this kind of atmosphere, what chance does a good bum joke have?

Breaking taboos and attracting reluctant readers

Bums have a foundational role in literature. Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale, Shakespeare’s frequent play on the word “ass” and Swift’s scatological obsessions are part of this rich inheritance. In children’s literature, bums have found a ready audience: children love to read about bodily functions. They know there is some level of taboo-breaking here and they love to break the rules.

So, books such as Stéphanie Blake’s Poo Bum, Dave Pilkey’s The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby, Mark Norman’s Funny Bums and Kate Maye and Andrew Joyner’s The Bum Book, sell very well.

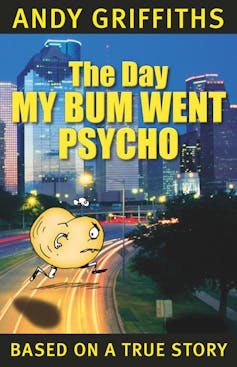

And I’m not sure what the Mississippi school superintendent would make of Andy Griffith’s international bestseller The Day My Bum Went Psycho. Here, the protagonist, Zack Freeman, finds that his own bum is part of a global conspiracy to cause a methane eruption that could render everyone unconscious while the bums take the place of people’s heads.

Griffiths, a former teacher, says he started writing humorous books as a way to engage reluctant readers. “Kids respond to humour. They are naturally playful with words and ideas. If you want a sure way to engage children, especially reluctant readers, then humour is necessary.”

Michelle Jensen, president of the School Library Association of NSW, agrees. “The book often needs to be funny, so that’s probably why they like Captain Underpants.”

Read more: Sex and other reasons why we ban books for young people

Irony, anxiety and why kids love bum books

Kids love bum books for reasons that are not immediately obvious, too. They know that use of words with light taboos will gain laughter and approval from peers. They learn that these words have a kind of power, and enjoy experimenting with this power.

When children call you a “poo poo” (knowing you are not, in fact, a “poo poo”), they are experimenting with irony, where they intentionally use the wrong word. They are showing that there’s no natural connection between a word and a thing, an understanding that helps them to absorb picture books, where there is often a disjunction between the word and the illustration.

Adults joke about things that make us anxious. So do children, who often have concerns about toilet accidents and can use language to discharge some of this worry. These books can also be used to initiate conversations about bodily processes, showing that they should not be embarrassing and we do not always control them.

And “disgust”, however it can be theorised, exerts a weird dynamic of attraction and repulsion on all of us. How else can you explain that there is a TV show called Dr. Pimple Popper?

Teachers fired for sharing LGBTQ+ books

In the United States right now, we can also imagine Toby Price being fired for reading a book about a queer kid, or about racial history.

In late 2021, Glen Ellyn, Illinois, third grade teacher Lauren Crowe was suspended because her TikTok site showed the LGBTQ+ material she used in class. Crowe was subsequently reinstated, as Illinois laws support the teaching of LGBTQ+ perspectives. But the incident seems likely to discourage other teachers from using similar books.

In 2015 in North Carolina, teacher Omar Currie felt compelled to resign after he read a gay-themed fairytale to his third grade students and caused a controversy that culminated in a town hall meeting with 200 participants.

Queer books for younger readers have saved lives, as children and teens who struggle with their own developing identity increasingly see their challenges reflected in fiction and know they are not alone.

Bum books, for all their good points, aren’t quite so noble.

But if they can ban the bum, they can ban anything – and that should worry us.

Simon Ryan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.