Christy Martin remembers the whistles and cat calls, the promoters who dismissed her as a sideshow and the times—so many times—she fought effectively for free. She remembers the dusty auditoriums in Asheville, Johnson City and Greenville, the opponents so unknown they were, in one case, literally unknown: Martin’s sixth professional fight, in September 1990, came against Jamie Whitcomb, though BoxRec, an official record keeper, notes that “some reports say Martin’s opponent name was Vickie Rice.”

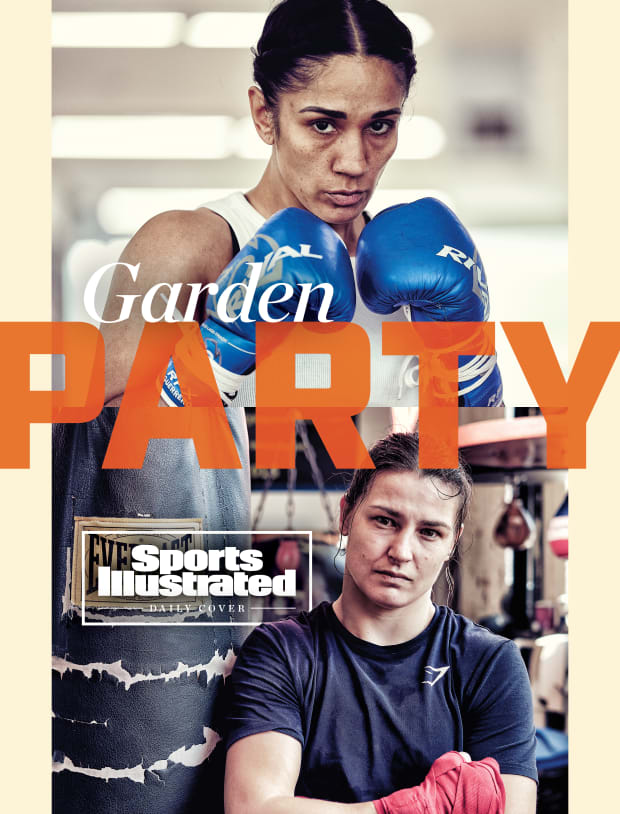

When Katie Taylor and Amanda Serrano step into the ring on April 30 it will be a watershed moment. Officially, Taylor’s four 135-pound titles, collected over the course of a brilliant, unblemished, six-year professional career, will be at stake. Unofficially, it will signal that women’s boxing has arrived. A women’s boxing match has never headlined Madison Square Garden in the arena’s fabled, 140-year history. When tickets went on sale in February, it was the second-largest boxing presale the building has ever had. When Shakur Stevenson–Oscar Valdez, an anticipated 130-pound title unification fight, was announced for the same date in Las Vegas, the buzz wasn’t whether the women’s fight would move to avoid a conflict, but the men. “This event,” says Eddie Hearn, Taylor’s promoter, “will be a monster.”

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated (top); Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated (bottom)

So how, exactly, did we get here? It wasn’t that long ago that Lennox Lewis’s manager described women’s boxing as “a freak show,” or Bert Sugar, the famed boxing historian, opined that most female fighters “looked like women going down in quicksand for the last time, wielding frying pans.” Martin often bristled at attempts to cast her as a trailblazer. “This is about Christy Martin,” she once said. Today’s boxers, though, see her as precisely that. Regular appearances on Don King’s closed circuit cards in the 1990s gave Martin visibility. Her slugfest with Deirdre Gogarty—on the undercard of Mike Tyson’s 1996 rematch with Frank Bruno, a bout that generated 1.1 million pay-per-view buys—gave her credibility. “That fight,” says Taylor, “put women’s boxing on the map.”

Martin’s pre-pro experience included a few wins in Toughwoman competitions (first prize: $1,000). By 1995, the New York Golden Gloves, U.S. amateur boxing’s most prestigious tournament, had created a women’s bracket. In 2012 women’s boxing made its Olympic debut, giving a global platform to the growing number of amateurs, including Taylor.

Also Read: Amanda Serrano Makes It Big By Teaming Up With a YouTube Star

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

Hearn admits he wasn’t interested in women’s boxing so much as he was Taylor. That early experience, though, opened his eyes to the possibilities. Women, says Hearn, “often delivered the same value to a show” as men, as well as being eager to take on the toughest challenges early in their careers. “They want to unify [titles],” he adds. “They are willing to take more chances.”

Understand: Women’s boxing still has a ways to go. Depth remains an issue. There are emerging stars, from Claressa Shields, the two-time Olympic gold medalist who has dominated the higher weight classes, to Seniesa Estrada, a brick-fisted 105-pound champion who is arguably the top fighter in three divisions. But they lack opponents to routinely make headline-caliber fights. Taylor and Serrano will be well compensated—both are guaranteed seven-figure purses, says Hearn—but compared with men, the pay scale remains wildly imbalanced. Hearn recalls a conversation he had with Taylor in 2018, when she faced Cindy Serrano—Amanda’s sister—in Boston. Taylor, by Hearn’s estimation, sold 60% of the tickets. Yet she was paid half as much as Tevin Farmer, a men’s titleholder on the card. In the locker room, Taylor asked Hearn whether he thought that was fair. “It wasn’t,” says Hearn. “Equality is not about giving someone the same money. It’s about giving someone who has the same value the same money.”

Also Read: Katie Taylor’s Improbable Path From Ireland to New England

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Taylor-Serrano is another step toward that. Like Martin-Gogarty, Taylor-Serrano—a 50-50 fight according to most experts—will be an event, a where-were-you-when moment beamed into televisions, smartphones and laptops globally. It will inspire women already in boxing and motivate others to jump into it. It’s women’s boxing’s first true super fight. It won’t be its last.

.png?w=600)