In April 1995, my uncle secured a lucrative job in Saudi Arabia. He and my aunt left their home in suburban Sydney and relocated to a western compound (a residential gated community for expats) in Jeddah. My aunt shares stories of life under Saudi’s strict laws and how she craved her western freedoms. One such freedom was the celebration of Christmas.

Hailing mostly from Australia, the UK and America, the compound residents organised their Christmases by smuggling in decorations and creating homemade Santa suits. They even staged the photographic rituals with mums and dads disguised as the shopping centre Santa Claus.

My aunt’s eagerness to recreate this photographic ritual with her children stems from her own childhood posing with Santa. My siblings and I were also photographed every year on Santa’s lap and we continue the ritual with our own kids.

As a photographer, I have spent years studying my curious desire to participate in this photographic custom. While I do not celebrate Christmas on religious grounds and bemoan the increasing consumerism of the season, I participate with overzealous enthusiasm in the Santa Claus photo.

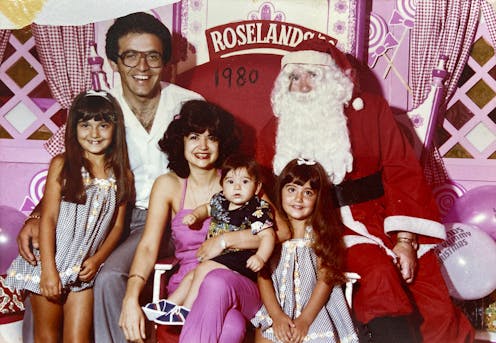

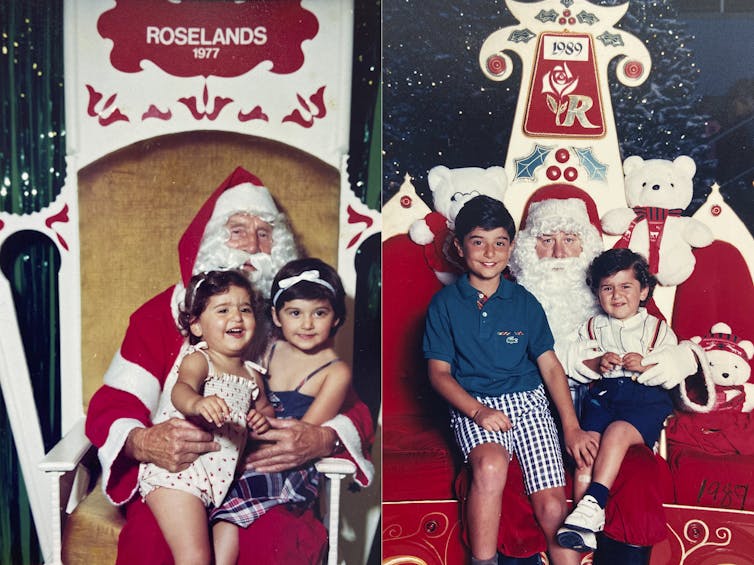

This is evident in the careful way I have cultivated the collection of my children’s Santa photographs between 2009-2018, and kept guard of my family’s collection from the 70s and 80s that portrays me alongside my siblings and, on one rare occasion, with my parents.

I use myself and my family as a case study. Analysing details like my mother’s obsession with dressing my sister and I in identical outfits, and then the ways I consciously made my children dress themselves.

The Santa photo feeds my photographic penchant for overly staged family portraits that signal to the camera “we are posing together for a photograph”.

Read more: The history of the shopping centre Santa, and how he became a staple of the festive season

Perfect Kodak moments

In Photography A Middle–Brow Art, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu famously observed in his 1965 study of amateur photography, that the family represents itself in “ideal moments of celebration” in order to secure its honourable social standing.

The Santa photos certainly fit this schema, tied to the so-called “Kodak moments” where everyone says “cheese”.

Instagram, which today operates as a public family album, reveals a searchable hashtag archive. Across #santaphoto, #santaphotos, #santapictures and #vintagesantaphoto you’ll find thousands of images of children sitting nicely on Santa’s lap.

Like most family photographs they serve a nostalgic function to take us into our pasts (with rose coloured glasses) and make us laugh at ourselves, at how we used to look, our hair styles, fashions, poses and reactions.

Today there are even photo sessions for pets, and “sensitive Santa photo sessions” for children with special needs.

With the rise of COVID-19, we see action packed beach Santa photos proving popular. In the shopping centre, the 1.5 metre social distancing rule is captured for posterity.

But Santa photos capture more than just the idealised moments of family life.

Read more: The borrowed customs and traditions of Christmas celebrations

Hilarious ‘Santa fails’

If the perfect family photograph is where the children are well dressed and everyone is posing and smiling happily, the “Santa fails” resist the ideal.

Santa fails show children reeling from Santa, throwing tantrums, back arching, crying and demanding to leave. Search #santafail on Instagram to see the truth of the matter: we happily and freely deposit our children onto the lap of a total stranger.

The artist Julie Rrap recently shared a story with me about her father who was once employed as a shopping centre Santa. He often reported coming home with a saturated lap from children having wet themselves while seated.

The comic relief that comes with such stories and the Santa fails are over time another ritual enjoyed among family members. But my attraction to the Santa photo goes deeper than comic relief of fearing Santa.

A work of art

As a migrant family in 70s and 80s Australia, we interpreted the Santa photo as a fun and unpretentious custom that assimilated us into the middle-class values of suburban Australia.

Participating in this ritual made us feel and appear more Australian, if only to ourselves.

I’m also interested in the Santa photos as a photographic typology. As a photographer, I have done what Bourdieu describes and “elevated the ordinary photo into a work of art”.

Through my training I have linked the seriality of Santa photographs to Rineke Dijkstra’s photographic portraits of Olivier and Almerisa. Photographing the same people over many years, Dijkstra captures the subtle changes in their appearance, mood and fashion style, as well as their social and political status.

I am also reminded of the playful fictional photographs of Christian Boltanski where the title of the work – 10 photographic portraits of Christian Boltanski 1946-1964, 1972 – leads the viewer to think they are looking at portraits of a boy growing up, when in fact they are reconstructions.

Like these artworks, Santa photos mark time, revealing what is imperceptible in everyday life. Through the repetition of a performance, a scene and an image we confront ourselves and the people we love changing.

Children and animals are notoriously the hardest subjects to photograph. The training a photographer receives with Santa photography is a baptism of fire. Moving subjects, crying babies, a toddler’s inability to sit still, scared children that won’t smile and toddlers engaged in escape attempts all combine with the parent’s consumer expectations that the photographer should get the right shot.

Remember, the next time you take your children, pets or yourself to have a Santa photo, keep in mind that the “right shot” and the best Santa photos are often not the ones where they’re smiling.

Read more: 10 months and hundreds of subjects: how I took portrait photography to the streets of Parramatta

Cherine Fahd does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.