Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

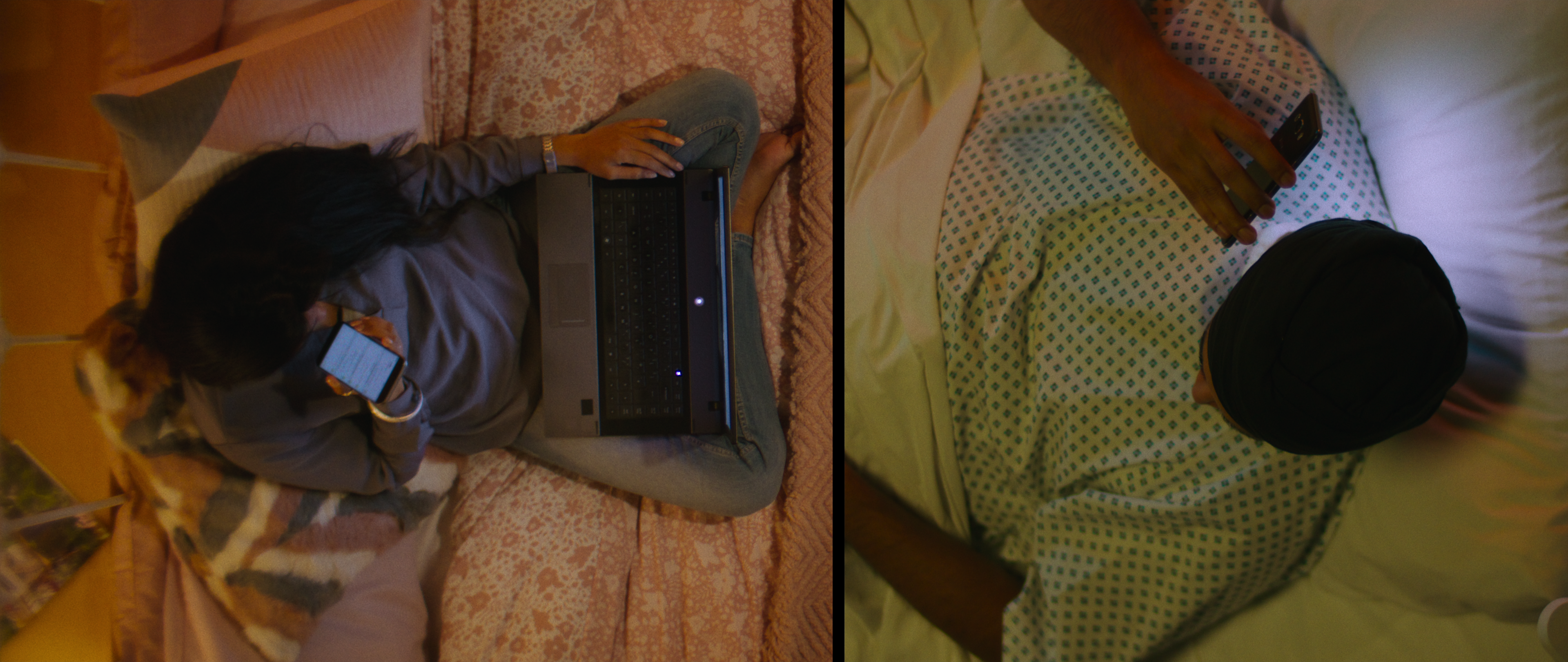

What would it feel like if, for eight years, you were in love with someone who was not who they said they were? If they introduced you to all their friends, but none of them actually existed? Or spent every night on Skype with you, listening to you sleep while refusing to ever show their face? Sweet Bobby, Netflix’s latest true crime documentary, introduces us to Kirat Assi, who experienced exactly that.

In 2009, Kirat fell prey to an elaborate romance fraud, carried out on Facebook, that went on until 2018. It involved up to 60 characters, each with their own fake profiles, who only existed in the scammer’s twisted imagination. At the centre of them all was Bobby, a handsome cardiologist from Kirat’s west London Sikh community. Bobby was a real person, but he wasn’t really the one talking to Kirat; it was her cousin, Simran Bhogal. Kirat, now 43, still doesn’t know why Simran – who was just a teenager when the lying began – tortured her throughout her thirties. “I had what I thought happened, and that’s just been ripped apart over the last few years,” Kirat tells me over video call. “I just don’t know what the truth is.”

The new documentary, out today, comes three years after Kirat’s tale of deception gripped millions of listeners in Tortoise Media’s podcast of the same name. “I thought it was going to be a small thing,” she says of the audio show’s release. Its popularity (it shot to No 1 in the UK podcast charts) has been vindicating. “With this documentary, I’m hopeful that other victims will feel that they can speak out against their perpetrators and feel safe going to the police or talking to people about it without feeling stupid,” she says.

Kirat’s experience is believed to be the longest known case of catfishing on record. It began when Simran’s ex-boyfriend, JJ, sent Kirat a message on Facebook, seeking her advice on how to win her cousin back. Months later, when Kirat was told JJ had died, Simran gave her the details for his brother, Bobby, so she could send her condolences. However, it was Simran behind Bobby’s scarily realistic profile. They became fast friends and he told her he was married, but soon began sharing details about his collapsing relationship. In 2013, things took a dramatic turn when Simran, posing as Bobby’s wife this time, shared a Facebook post saying that Bobby had been shot several times in Kenya and was in a coma.

Simran, whose family were friends with Bobby’s, would later call Kirat to tell her that Bobby was now in witness protection in New York. “It was like something out of a movie,” Kirat admits in the documentary. This ruse allowed Simran to start messaging Kirat from a new fake profile, claiming it was Bobby under a new name to protect his identity. Disaster continued to strike fake Bobby: his marriage ended and just over a year later, in 2015, he suffered a brain tumour, followed by a stroke. Conveniently, this meant he was unable to speak over the phone and the witness protection scheme forbade him from appearing over video call. At various points in the film, viewers may question Kirat’s naivety, but the lies were always substantiated by Simran’s cast of supporting characters, such as Bobby’s doctor, Rajvir, or his cousin, Yashvir – all of whom were messaging Kirat, but none of whom were real.

One of the most emotional moments in Sweet Bobby comes when Kirat is played a farewell message she recorded when she was told Bobby was going to die. At that point, Bobby had told Kirat that he loved her but she hadn’t said it back. “It was horrible to think that he might die,” she tells me. “... You carry a lot of guilt for not giving the person what they want.”

Of course, Bobby didn’t die; he miraculously recovered, and the relationship intensified. They began Skyping constantly, even falling asleep with the line open. The sound of the Skype ringtone is still triggering for Kirat, she tells me, which is perhaps one of the reasons we’re speaking over Google Meet today. Very quickly after the relationship turned romantic, Bobby began to display signs of coercive behaviour. He demanded to know Kirat’s whereabouts at all times, dictating who she saw and spoke to, and guilt-tripping her about his health if she dissented. “It was like Bobby owned my time now,” Kirat says in the film. Through a series of daily selfies she shared with Bobby, where she gradually becomes thinner and more worn down, viewers see how Kirat’s own health declined. She was eventually made redundant from her job in marketing.

Finally, after years of broken promises to meet in person, Kirat hired a private investigator who found that Bobby was living in Brighton, and she confronted him there. When she turned up at his door, the real Bobby, who also appears in the Netflix special, was mystified and scared. The next day, Simran drove to Kirat’s home and confessed: “It was me; I was Bobby, I was all of them.” On the podcast, Kirat said she “vomited” and “passed out” after the revelation, which came in June 2018. “I just kept screaming at her, ‘Why? Why Did you do it?’” Kirat says in the documentary. “She’s ruined my whole life. She’s stolen the best years of my life off me and all she could say was that I ruined my own life. No expression, nothing.”

In 2020, Kirat won a substantial settlement in her civil case against Simran for harassment, misuse of private information and data protection breaches. As part of the ruling, she received a private apology from Simran, which Kirat is not allowed to discuss. But she tells me she doesn’t “feel there’s ever been any remorse”. “Personally,” she says, “I feel like there’s a defiance or an element of arrogance about the situation.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Despite Kirat’s legal victory, Simran has still not been charged with a crime. Up until 2021, she was reportedly working a “high-powered job” in financial services, but quit when the podcast went live. The criminal case has since been reopened, says Kirat, but the system for dealing with catfishing cases is in dire need of reform. In the UK, catfishing is not a criminal offence. And when Kirat first reported Simran to the police, she was told she wasn’t a victim, but the real Bobby was. “It’s made as difficult as possible for you to want to pursue your case, and it’s you versus the police,” she says. “Everything has been a struggle every step of the way.”

This year, Richard Gadd’s Baby Reindeer has shone a light on online harassment and the stigma that victims of abuse often face. Kirat has watched the series, which is based on Gadd’s real-life stalking experience, and tells me the scene she found most triggering was when Gadd’s Donny reports his stalker but is quickly rebutted by the authorities. “That almost made me want to throw up,” Kirat recalls. “The hardest thing was being told to just quietly move on without people understanding the damage it had done and the trauma that it had caused.” Echoing Kirat, Gadd told The Independent in 2019 that police “look for black and white, good and evil, and that’s not how it works. You can really affect someone’s life within the parameters of legality, and that is sort of mad.”

After Baby Reindeer aired on Netflix, fans quickly began a frenzied search to discover the true identity of Gadd’s stalker – and they succeeded. Is Kirat concerned that people will try to track down Simran, too? “Yeah, I am concerned,” she says. “Anyone who wants to do that, I’d be like, ‘You’re as bad as her if you’re doing that.’ What we need to do is put pressure on the authorities to do the right thing. I could have banged her door down or sent thugs around, but no, that’s not the right way to do things. I think the right way to do things is highlighting the issue, which is what I’ve had to do.”

Matters are made yet more complicated by the fact that Simran and Kirat are related. “People have to realise a witch hunt against her also impacts my family,” she says. “So to instigate witch hunts against these people that were named in the public like that is just poor form.”

Today, Kirat is pragmatic and “quietly determined”, she says, to reclaim the life she feels was stolen from her in the years she had hoped to meet a life partner and have children. First, she wants to see Simran face the legal justice that has long been overdue. “It’s been dragging for years now. I can’t move forward properly until that’s done,” she says. Her cousin wreaked such havoc, for such a long time, that Kirat still feels life is “nowhere near what it used to be or what I want it to be”. She sighs. “Hopefully I’ll get there.”

The Cyber Helpline has a dedicated page relating to catfishing or digital romance fraud. If you think you might be at risk, there are tips for recognising a scam and also suggestions for how to deal with it.

If you have been a victim of catfishing and need emotional support, then you can call the Samaritans. Their free phone line is available 24 hours a day. You can also call Victim Support or Victim Support Scotland.