In the last 10 years, vaping has become many people’s — and especially teens’ — preferred means to consume nicotine or cannabis. But unlike cigarettes, which have been around for hundreds of years, vapes and e-cigarettes are mere decades old. And that means scientists and doctors don’t fully understand the long-term effects of vaping on the brain and body in the same way they do the ill effects of cigarettes.

But vape technology’s intended purpose, Carolyn Baglole, a respiratory toxicologist at McGill University, tells Inverse, was to help smokers quit cigarettes. These battery-powered devices contain nicotine like cigarettes — but they deliver it as an aerosol made from heating up a nicotine-containing oil in the vape, a method of ingestion that delivers fewer toxins than cigarettes, like tar, in each puff. But beyond being “better,” precisely what difference vaping makes to a user’s long-term health than smoking is less certain — but a new study co-authored by Baglole does bring scientists a little closer.

A new study published in the journal Federation of American Sciences for Experimental Biology involving mice examines what the study authors deem to be “chronic, low-level” vape usage — essentially taking a few puffs here and there. They find that as little as a month of casual vaping may wreak unseen damage upon lung cells in users.

LONGEVITY HACKS is a regular series from Inverse on the science-backed strategies to live better, healthier, and longer without medicine. Get more in our Hacks index.

Science in action — Baglole and her colleagues ran a four-week trial on mice aged eight to 12 weeks. During the four-week period, the mice were exposed to 59 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter from a pod made by the popular vape brand JUUL. After the exposure period, the researchers then performed an analysis of the mice’s cells to see if there were changes at the molecular level.

“We did see that inhalation of these products in this preclinical model really did cause substantial changes within the lungs,” Baglole tells Inverse.

One big change was the presence of neutrophils in the lungs — these immune cells typically rush to help quell inflammation resulting from an injury. In other words, the mice’s bodies appear to have reacted to the exposure to vaping as an injury to the lungs. Deeper changes also occurred in lung cells’ RNA — a molecule that’s essential to coding, regulating, and expressing genes.

Compared to mice that were not exposed to the JUUL pod, the vape mice had “massive transcriptomic changes” at the RNA level, according to the scientists. In particular, it appeared to affect pathways containing genes and proteins that help our bodies break down and metabolize inhaled chemicals or drugs.

Importantly, Baglole says, these results don’t speak to the effect of secondhand vaping.

Why it’s a hack — Vaping has demonstrated success as a way to help smokers quit, but it is not inherently safe, either. Baglole says that compared to smoking, vaping is a less risky alternative, but advises that non-smokers stay away from e-cigarettes.

“People should definitely quit smoking if they’re current smokers, but if you don’t inhale anything, this is not something you should pick up and start,” Baglole tells Inverse. While vaping could be a hack to help quit smoking, in non-smokers, it has the potential to introduce damage to the lungs where there was none before.

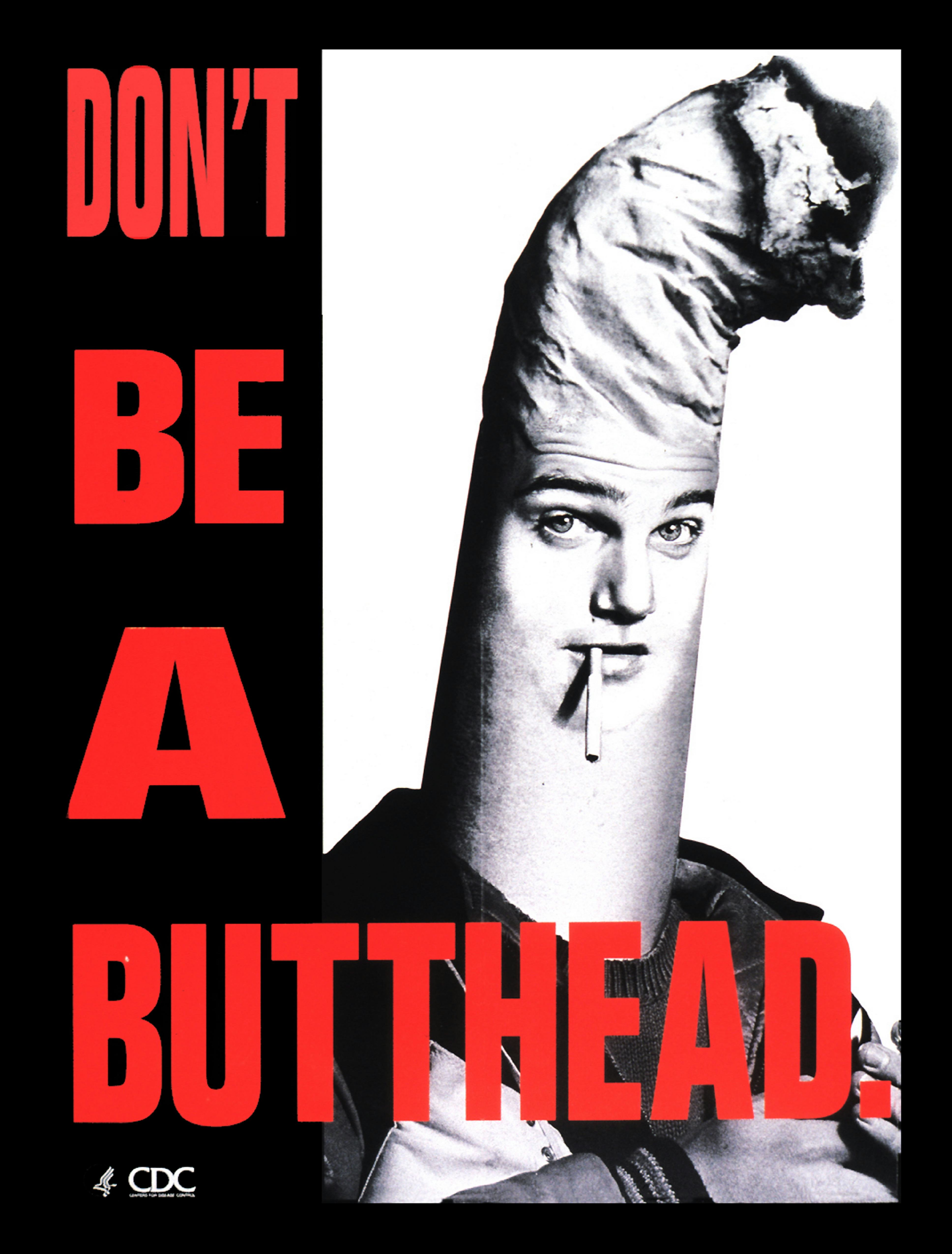

Another noted drawback to e-cigarettes is that they’re enticing to young people, partly because of the flavored oils and false sense of safety. Indeed, a 2014 review highlights the perceived safety of a product that contains fewer chemicals than a cigarette.

Right now, there are still many unanswered questions about vaping and health. For example, Baglole says that researchers still need to study the compound effects of vaping and, say, asthma, which could result in worse long-term health outcomes. Ultimately, if you have never smoked, don’t be tempted to see vaping as a risk-free way to give nicotine a whirl.

How it affects longevity — Smoking cigarettes is a well-established risk factor for premature mortality and a bevy of chronic health problems, including various cancers. E-cigarettes may not be as well-studied as their analog predecessor, but the new research suggests they are best avoided, too.

Other research suggests vaping causes severe acute lung injury, but scientists are still trying to understand how vaping drives disease. Baglole emphasizes that the results from her study demonstrate that even low-level vaping induces changes to mouse lung cells on a molecular level — but she doesn’t yet know if those changes result in severe illnesses. But the fact that chronic, occasional vaping tweaks our bodies at the cellular level means that it is a worthy hypothesis for future study.

“People should make, of course, every effort to quit smoking,” Baglole says. “If [vaping] is a tool that somebody that cannot quit by other means — this could be a very valuable to tool for them, and then hopefully wean off any type of substance related to nicotine inhalation.” In other words, don’t get too comfortable with the vape.

Hack score out of 10 — 🚭🚭🚭🚭 (4/10 no-smoking signs)