Susie Ibarra and Richard Reed Parry had heard each others’ heartbeats — in many different forms — before they ever met IRL.

The artists had been commissioned by Splice in partnership with new record label OFFAIR — a venture between Universal Music Canada and Versus Creative that seeks to create deeper experiences through music — to conduct a relatively simple experiment: create music centered on the human body’s rhythms. Rather than recording to the beat of a metronome, Parry and Ibarra would compose to the rhythm of their hearts and breaths.

Parry, who is perhaps best known for playing an assortment of instruments as a core member of hit band Arcade Fire, has found inspiration in unusual places before; his two-part 2018 album Quiet River Of Dust pulls from such disparate sources as British folk songs and Buddhist myths. He’s no stranger to collaboration, either, though he and Ibarra had never crossed paths before this project, in the music world or otherwise.

This isn’t exactly surprising: Ibarra and Parry, though both musicians, run in entirely different circles. Ibarra is a percussionist who’s worked extensively on field recordings of indigenous Philippine music and conducted novel musical practices like working alongside a glaciologist to record glacial soundscapes.

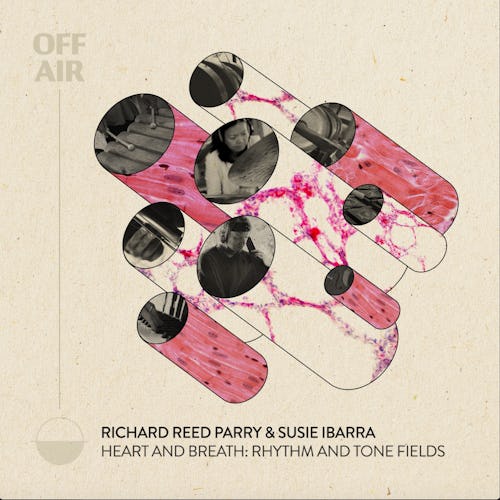

Despite their largely divergent careers, Ibarra and Parry were able to find common ground in listening and reacting to the human body’s natural rhythms. The pair spent many hours listening to their hearts (literally) to create the nine-track album Heart and Breath: Rhythm and Tone Fields. The work is being released as both a full album and as a pack of samples, which Ibarra and Parry hope will be taken up by others interested in their project. They’ll be performing the work IRL soon, too, and even plan to use audience members’ heartbeats to inform the live music.

Input talked with Ibarra and Parry about how they went about recording such an untraditional album and how they hope their bodies’ rhythms will affect listeners.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you two begin this process?

IBARRA: Well, Richard had already been developing this idea of creating music with heart and breath cycles. I thought it was very interesting because it also connects to lots of things in traditional music structures in many cultures. It’s something so innate to a performer — it’s a practice.

PARRY: It was a basic idea I had many years back. It occurred to me: Why had no one ever done this explicitly before? Heartbeats and breathing are the most universal rhythms we have. No one had ever really stuck to those things to guide music. I wrote some music around it but felt I had only really scratched the surface in a looser and more embodied way of composing. Susie and I approached it in a more performance-based way.

IBARRA: As a percussionist, I’m always connecting to that heartbeat, but what I think is really wonderful is making these ancient traditional practices connect to contemporary music, to understand that they can be more intentional and less subconscious.

It sounds like a lot of improvisation. Did you set out to write something specific, or did you mostly write in the moment and edit later?

IBARRA: We’re not scoring it in a traditional Western way. We’re sharing these parts and composing it back and forth with each other. It’s more about the whole body.

PARRY: It would start as improvisations from one side or the other, and then we’d cut it up into movements, and structure around sounds we’d already created. It ended up sounding quite live in certain ways, like an ensemble in a room. That way of improvising with a central rhythm that’s — but not a metered one — it was a unifying element that let us be cohesive from hundreds of miles apart. We got to be loose and sprawling, following our own rhythms, but we were still unified by that musically.

IBARRA: We’re not playing to a click track or a tempo we’ve decided upon. We’re playing towards what our bodies are telling us.

PARRY: Listening to it back has a very specific feeling, it’s hard to put your finger on it.

What kind of technology did you use to listen to your heartbeat? Was there a specific piece of hardware?

PARRY: Oh, yeah. A very specific piece of hardware. A stethoscope.

[pause for laughter]

PARRY: I have a digital stethoscope as well as a normal one. But it’s impossible to use the digital one while you play, because it’s amplifying everything that’s going on, including the instrument you’re touching. Actually, one piece I did record like that because the song has an audible heartbeat. Playing with a stethoscope in your ears is awkward, but you can do it.

My heartbeat is fairly irregular, which you can hear in some of the pieces. It’s kind of cool, there’ll be a hiccup in the rhythm or a jump in tempo. Sometimes that gets smoothed out through the natural process of two people playing together. When you follow one person’s pulse really closely you can get a pretty tight rhythm section going.

It’s one thing for a single person to play along with their own heartbeat, but it must’ve been difficult to put your heartbeats together. Were you able to do that?

IBARRA: Yes, it’s very difficult. I play percussion, so I’m usually louder. Sometimes the stethoscope just wasn’t loud enough. I needed to take recordings and listen back to them sometimes.

PARRY: A friend of mine is developing a performance interface for us to use when we’re performing it live as an ensemble. We’ll basically have a sensor picking up our heartbeats and then sending it out as a sound to each person in the ensemble. We’ll be able to mix and match this way, with everyone listening to one heartbeat or multiple, maybe even with some audience participation.

Have you had the chance to perform it live yet?

IBARRA: No, not yet.

I’m guessing it’ll sound very different live, like if your heart rate is speeding up on stage.

PARRY: Right. Part of it is committing yourself to this rhythm that’s outside of your decision-making process. Committing to playing to your own heartbeat while Susie plays to hers, knowing things will go in and out of sync because that’s how bodies work. That opens up musical spaces and mental spaces for a performer.

IBARRA: Definitely.

PARRY: You’re following this interior metronome. This other presence, if you will. It really decentralizes your own musical control system in your mind.

IBARRA: The intention is so different that you play differently.

PARRY: And the audience listens differently. You open up this listening space for people. They know they’re listening to the musicians listening to their heartbeats or their breathing. A really unique quality can emerge from that.

IBARRA: In a lot of Southeast Asian percussion music, the time is always expanding and contracting, especially in gong music. It puts your body in a different state — I can’t drive while I listen to it. I have a similar reaction to this album.

PARRY: Listening to it is kind of hypnotic, it puts you in a kind of alpha state.

IBARRA: We’re always in these polyrhythmic states, we’re always shifting, but we’re not always aware of that. In this case, we’re actively and intentionally aware. And we’re inviting the listener to experience it with that intention.

PARRY: It’s divorced from the top-down brain logic that usually drives musical performance. When you listen, you can feel there’s a different logic system at play. It’s not brain logic; it’s body logic. You’re released from the hierarchy of meter.

IBARRA: Our decision-making is totally different. When I’m practicing polymeters, I have to place everything in my body. It’s a practice where the heart and the breath are asking us to listen and play from our bodies.

PARRY: You have to relinquish the normal controls you hold as a musician.

Can you tell me about the sample packs you’re releasing for the project? Did thinking about the sample packs change your compositional process?

PARRY: The sample packs are basically elements of the record taken apart.

IBARRA: It became a very inclusive process because we knew we were making both an album and sample packs.

PARRY: I ended up thinking of it as an entire composition, which is how I approach all my music, and figured the sample elements would present themselves. I didn’t really think about the samples much while writing the music. I knew the most beautiful and interesting samples would become apparent.

Is there anything you’ve learned during this experiment that you’ll take with you in your future music-making?

PARRY: It’s a nice self-contained world in some ways. But any avenue you explore can become an avenue you revisit.

IBARRA: The process became very layered, especially in thinking about how we’ll transpose this as live elements. And I really love where we arrived. It’ll definitely influence how I might listen to and think about things in the future.

Updated 6.22.22, 5 p.m., to correct information about Parry and Ibarra’s comission.