In a Senate committee hearing earlier this month, Greens Senator David Shoebridge asked the question that many had been wondering: “If you are testing to see if someone is 13, 14, 15 or 16, you are also testing to see, by definition, if they’re 16-plus. If there is going to be age verification, everybody will have to go through an age verification process, won’t they?”

The answer from the deputy secretary of the communications and media group at the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts James Chisholm was simple: “Yes.”

The framing of this national age assurance scheme as a teen social media ban has already been criticised — including by Crikey’s own Cam Wilson, who wrote that “the teen social media ban isn’t just a policy about children using the internet — it’s about how we all use it.” And yet, the Australian government’s public discussion of the policy has remained focussed children and teens, despite the potential that they too will be impacted by the privacy risks associated with age assurance.

While protecting children remains a compelling — and important — intention, if we are to accept the government’s framing that this policy will be impacting children, regardless of the age assurance method used (facial recognition, digital ID or something else entirely), it will subject children to increased monitoring and datafication. If this is seen by the government as acceptable, or at least politically effective, it’s worth considering whether the surveillance of children has become normalised.

Technology-enabled surveillance starts before birth. Professor Tama Leaver wrote in a 2017 journal article that “Pregnant women are both watched and viewed through, in order to monitor the unborn, and apps facilitating this monitoring often raise significant privacy issues as well as inherent questions about the veracity of the information they provide.”

“Like pregnancy apps, infant wearables and related devices and practices contribute to the ongoing datafication of infancy, where infants are rendered as data which simultaneously provide reassurances about their well-being to parents while being aggregated and analysed as elements of big data sets.”

After birth, the internet of things ensures that everything from infant wearables to toys gifted by well-intentioned family and friends also collect a child’s data. As they grow older, children become increasingly likely to be surveilled further, as parental tracking apps and devices continue to grow in popularity despite concerns from experts.

This is not to say that parents do not care about their children’s privacy. In the information commissioner’s 2023 Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey, 94% of responding parents were concerned about their children’s privacy, with 65% being “very concerned” and 29% “somewhat concerned”. This has increased since 2020 where 51% were “very concerned” and 40% were “somewhat concerned”.

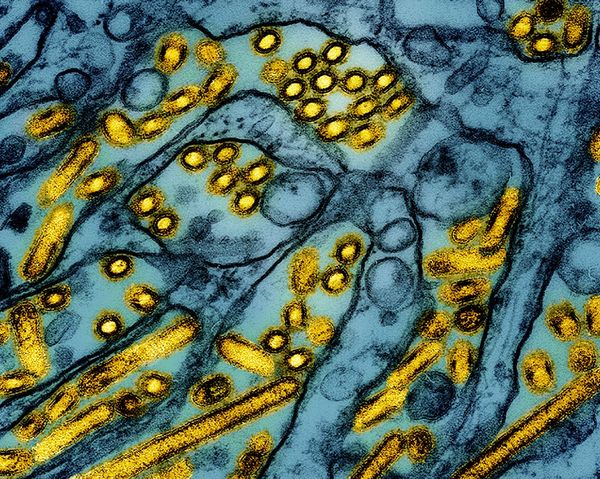

During the COVID-19 pandemic, education technology (EdTech) connected school-aged children with their teachers — and with a variety of third-parties including advertisers. An investigation by Human Rights Watch into 164 EdTech products from 49 countries (including Australia) found that 89% appeared to use data practices that infringed upon, or risked the infringement of, children’s rights. Many of these often education-focussed apps and websites had the potential to monitor children, collecting data on them, their classmates, their devices, their location and more.

Even in physical education environments, children cannot escape technology-assisted surveillance. Facial recognition and detection technologies have been designed for security systems, automated attendance, and attention monitoring in schools. In a 2020 journal article, Professors Mark Andrejevic and Neil Selwyn write that “facial recognition technologies have so far faced a relatively unhindered passage into schools”. This is despite the fact that “unlike social media posts or interactions with school learning management systems, there is no option for students to self-curate and restrict what data they ‘share’.”

From their bedrooms and classrooms to their own devices, children face vast potential for tracking and surveillance. In an essay for Overland, digital rights activist Samantha Floreani wrote, “The danger of using polarising language and tactics in a rights context is that it forces people to make false choices. It was never privacy or public health, just as it’s also not privacy or safety.”

Amid the many valid debates about social media, it’s important to remember that it doesn’t have to be a choice between protecting children and protecting privacy. It can be both.

Do you support the government’s teen social media ban? Are you worried about potential privacy implications? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.