Temperature spikes above Antarctica in July represent the earliest warming of the stratosphere ever recorded, NASA observations show.

Atmospheric scientists have been closely monitoring this region of Earth's atmosphere, which extends from about 4 to 31 miles (6 to 50 kilometers) above Earth's surface, during the Southern Hemisphere's winter. Lawrence Coy and Paul Newman, both atmospheric scientists at NASA's Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO), create elaborate data assimilation and reanalysis models of the global atmosphere and have paid close attention to unusual and "surprising" warming events.

Usually, the temperature in the middle stratosphere, roughly 19 miles (30 km) above Earth's surface, is around minus 112 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 80 degrees Celsius), but on July 7, there was a leap of 27 F (-3 degrees C) to -85 F (-65 degrees C). This spike set a new record for the warmest July temperature detected in the stratosphere above Antarctica.

"The July event was the earliest stratospheric warming ever observed in GMAO's entire 44-year record," Coy said in a statement.

It lasted two weeks, before dipping back again on July 22. There was a brief lull before another surge to 31 F (-1 degrees C) on Aug. 5.

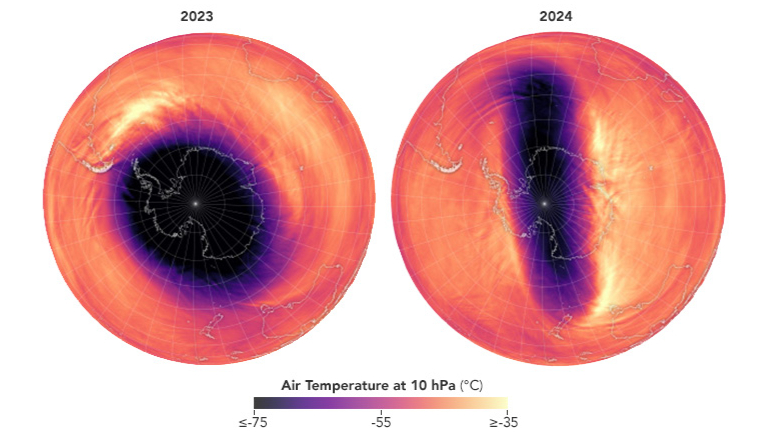

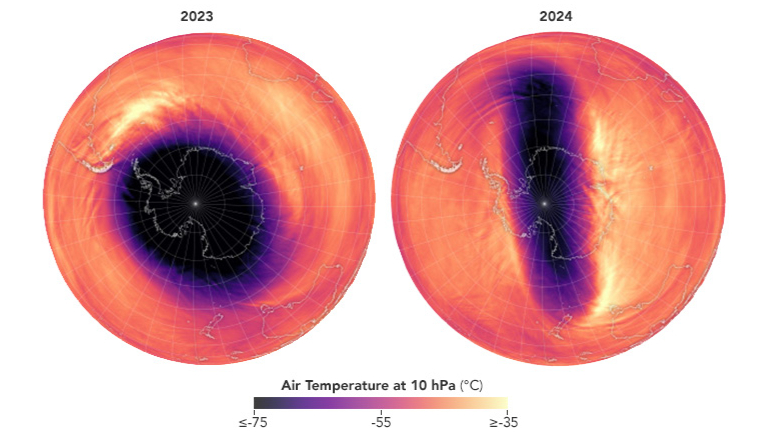

In the winter, the stratosphere is dominated by westerly winds that loop around the South Pole at around 200 mph (300 km/h). Commonly known as the polar vortex, the flow around the poles is normally symmetrical. However, sometimes, there is a disruption to the flow, and when the winds weaken, the shape of the flow is altered. When the polar vortex becomes more stretched out, the winds decrease, leading to significant warming in the stratosphere over the Antarctic region.

Related: Satellite data reveals Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier is melting faster than we thought

The Southern Hemisphere's polar vortex normally remains less active than its Arctic counterpart. "Sudden warming events happen in the Antarctic once every five years or so, much less frequently than the Arctic," Coy said. This is likely because the Northern Hemisphere has more land, which can disrupt the wind flow in the troposphere, the lower atmospheric layer near the ground, he explained. Large-scale weather systems that develop in the troposphere and progress into the stratosphere can affect the polar vortex.

The tropospheric weather in July above Antarctica also tied July 1991 as the fifth-warmest July observed for the region. However,the sudden warming of the stratosphere does not necessarily have a clear connection to the weather, Newman noted.

"Variations in sea surface temperatures and sea ice can perturb these large-scale weather systems in the troposphere that propagate upwards," Newman said in the statement. "But the attribution of why these systems develop is really difficult to do."

Editor's note: This article was updated at 12:05 p.m. EDT on Sept. 16 to correct some temperature conversions between Fahrenheit and Celsius.