As the founder of Birmingham’s House of God club nights, Anthony Child (aka Surgeon) was one of the first DJs to import techno into the UK scene during a golden era for the genre.

Always keen to develop his technique and get to grips with new technologies, Child was also one of the first to introduce CDJs, Ableton Live and Final Scratch into his DJ sets.

Child moved into production in the early ’90s with his seminal debut EP Surgeon (1994) introducing a tough, industrial slant. A constant presence on the techno scene, his uniquely sophisticated production style has developed to incorporate elements of funk and dub across a catalogue of influential releases for labels such as Tresor and his own Dynamic Tension.

In recent years, Child has increasingly investigated ways to switch-up his creative process. Turning his attention to the spontaneity of live performance, Crash Recoil – Child’s first album in five years – sees the producer transpose the self-limiting constraints of his live set to a home studio setting. The result is a raw, crunching and untethered techno album that, nevertheless, sounds unmistakably Surgeon.

You started producing at a time when industrial music was reaching its peak. Did you set out to create a toughened version of techno that would borrow from that scene?

“In retrospect, I feel that I may have misunderstood what industrial music was. For some people, industrial music is Ministry or the American rock version, which has never really appealed to me. I grew up with bands like Coil, Psychic TV and Throbbing Gristle and was influenced by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut-up techniques.

“When I make music I never approach it thinking I’m going to make an industrial or disco track, I work in a more intuitive and improvisational way and follow where the feeling is. I’m trying to make something come to life rather than set out from the perspective of a particular idea.”

In what way were Gysin’s cut-up techniques important to you as a producer?

“I was very young when I came across Gysin. I’d only ever heard pop music on the radio and watched films on TV with straight narratives, so it blew my mind to see how Gysin would tear up text and rearrange it. It blew the doors open in terms of the possibilities, but I didn’t start picking up a camera and cutting up film, it just made me think differently about how you can rearrange or decontextualise anything, whether related to visuals or sound.”

Initially, techno was very much inspired by new technology. Did that seduce you?

“For me, technology is very much a means to an end. People might be surprised, but I don’t have a keyboard fetish. They’re just tools to create with and when I first started making techno I used whatever I could get my hands on or borrow. Looking back, I had to be really inventive about how I used and processed sounds with very basic equipment. Over the years, I’ve had the budget to buy more gear but it took me many years to realise that restrictions were actually a good thing.

“It’s that thing about having infinite plugins on your computer and how they can often be more of a curse. So I don’t have a studio where everything’s set up and connected to a patch bay, I just pick some gear, create a live setup on a little folded table and work on projects using that ideology.”

Artists who start with a basic setup often look back and wonder how they managed to squeeze so much out of it and are sometimes puzzled that they can’t achieve the same results now…

“I’m sure that a lot of artists are asked why they can’t replicate the music they made 20 years ago, but there are several reasons for that. Music is tied to an era and is about the person you were at the time. I’m not that person now and I’m not in that headspace, so I can’t draw the same things out of me.

“My approach has always been to travel forward. I’ll use a way of recording or combinations of gear and when I feel like I’ve done all I can with those I’ll change the combination or technique. I’ve performed that way as a DJ too. I started with vinyl and then tried using CDJs and technologies like Serato, Final Scratch and Ableton. There could be a good reason for going backwards, but only if I can do it in a new way or feel like I’m pushing ahead.”

Crash Recoil is your first album in five years, which obviously encompasses the pandemic. Was that a moment of reflection and re-evaluation for you?

“I wouldn’t relate this album to the pandemic as I wasn’t very active or creative during that time. I looked at my options and didn’t really come up with anything [laughs]. By that point I’d been touring and DJing for 30 years and been involved in the whole electronic music/techno timeline for quite a while, so to have an 18-month interruption was really weird and I think we’re all still figuring out the after-effects of that.”

Did you consider live streaming?

“I’m not a huge fan of live streaming, but I did do an event where I was filmed DJing in an empty club and that was bizarre. When you watch a live stream, you’re given the impression that you’re watching a performance, but you’re not – you’re watching coloured pixels on a screen.

“A performance is made of the room, the acoustics, all of the people who are there and how warm the beer is. Without that, there’s something missing. I love the exchange of what I call ‘animal energy’, where there’s this feedback loop between the audience and the performer – that’s why I love doing it.”

As mentioned, the new album originates from certain parameters that you adhere to in your live performances. What was the thought process behind that?

“The whole idea originated from a live set that I’d been touring with for 10 months. I had a sequencer set up with eight groups of patterns – let’s call them songs – based on MIDI sequences such as drums and other triggers and melodic parts. Those patterns were very open-ended. They all made sense and related to each other musically, but I wouldn’t necessarily use all of them at the same time or during the same performance.

“That means there was a big improvisational aspect to my shows, working from a bunch of musically coherent starting points. You could equate it to a band performing a bunch of songs – over time, you really get to know what those songs are and are able to find the soul and spirit of them. I created the setup purely to perform live with no intention of using any of the material in the studio, but then people started saying that I should turn them into tracks and I drew encouragement from that.

“After the tour, I went into the studio to record these eight tracks over the course of a couple of weeks already knowing what the songs should be. I recorded all of the different parts and arranged them in Ableton, and that was the album. The tracks are even in the order that they appeared in the live set.”

What gave you the impetus to use more improvisation during your live sets?

“I’ve been exploring live improvisation using many different approaches for around eight years. It started off with me getting into the whole modular thing. At one point I brought some modular along to a DJ gig, played around with it and found that it was so much fun that I was no longer DJing.

“I kept improvising with modular and continued to develop that skill for around three years until I became involved in an improvised live project called The Transcendence Orchestra with Daniel Bean. We released three albums on Editions Mego that are more drone-based and those live performances are even more abstract than my techno sets where people at least know that some form of rhythm is going to be involved. Exploring those improvisational avenues then became the way I wanted to perform live, by not recreating existing songs but creating new pieces on-the-fly.”

Some people are cautious about performing with modular equipment in an improvisational setting. How did you conquer that?

“I’m impulsive and stubborn. If I get an idea that’s exciting to me I’ll just go with it without considering the dangers, but that’s part of the fun too. You’re standing on stage and about to start playing in two minutes and suddenly have this realisation that you have nothing prepared. I find that exciting. It’s a bit of a paradox, but I actually find it harder to deliver a live set where the structures are all set out.”

Does that suggest that you find it more difficult when you have time to think about what you’re doing?

“I just find that it’s easier to feel what I have in front of me and be totally in the moment. Not only is that really powerful, but it transfers to the audience too. One of the most exciting things about live performance is that sense of risk. Not just for the performer, but when the audience feels like everything could all go horribly wrong because they’re participating in that risk.”

Going into that situation, do you need complete mastery over the tools you use?

“Being comfortable with the gear you’re using is a big part of it. I often see people performing live techno with a table full of gear who clearly feel that adding another synth will add a safety net, yet there’s often too much gear for them to keep on top of and that actually makes things more stressful.

“You’ve only got two hands, so unless you get another person involved you need to reduce the setup to feel comfortable operating it. It’s funny, but people seem to desperately want to know what gear I’m using. I’m fine with sharing that, but the setup that works for me probably wouldn’t work for another person and it’s important to find the setup that works for you.”

Should the music be the entire experience? For example, Richie Hawtin’s Close Combined used 4K cameras to give the audience more insight into what he’s actually using and doing on stage…

“I’m a fan of mystery. The first rave nights I went to didn’t have an emphasis on where the DJ was – the focus was really on the music, and how the crowd interacted was very important to that scene.

“The closest thing to what you’ve mentioned is when I took part in a live show with Speedy J called STOOR at the Amsterdam Dance Event. They had a big table set up in the middle of the room with five people around it and everyone’s gear was synced. We played six hours of improvised techno and that was fun because we didn’t have monitors and heard the sound system in the same way that the audience did. They watched the whole performance from various balconies and could see what we were all using.”

In relation to Crash Recoil, can you take us through the technologies you’re specifically using in your live setup?

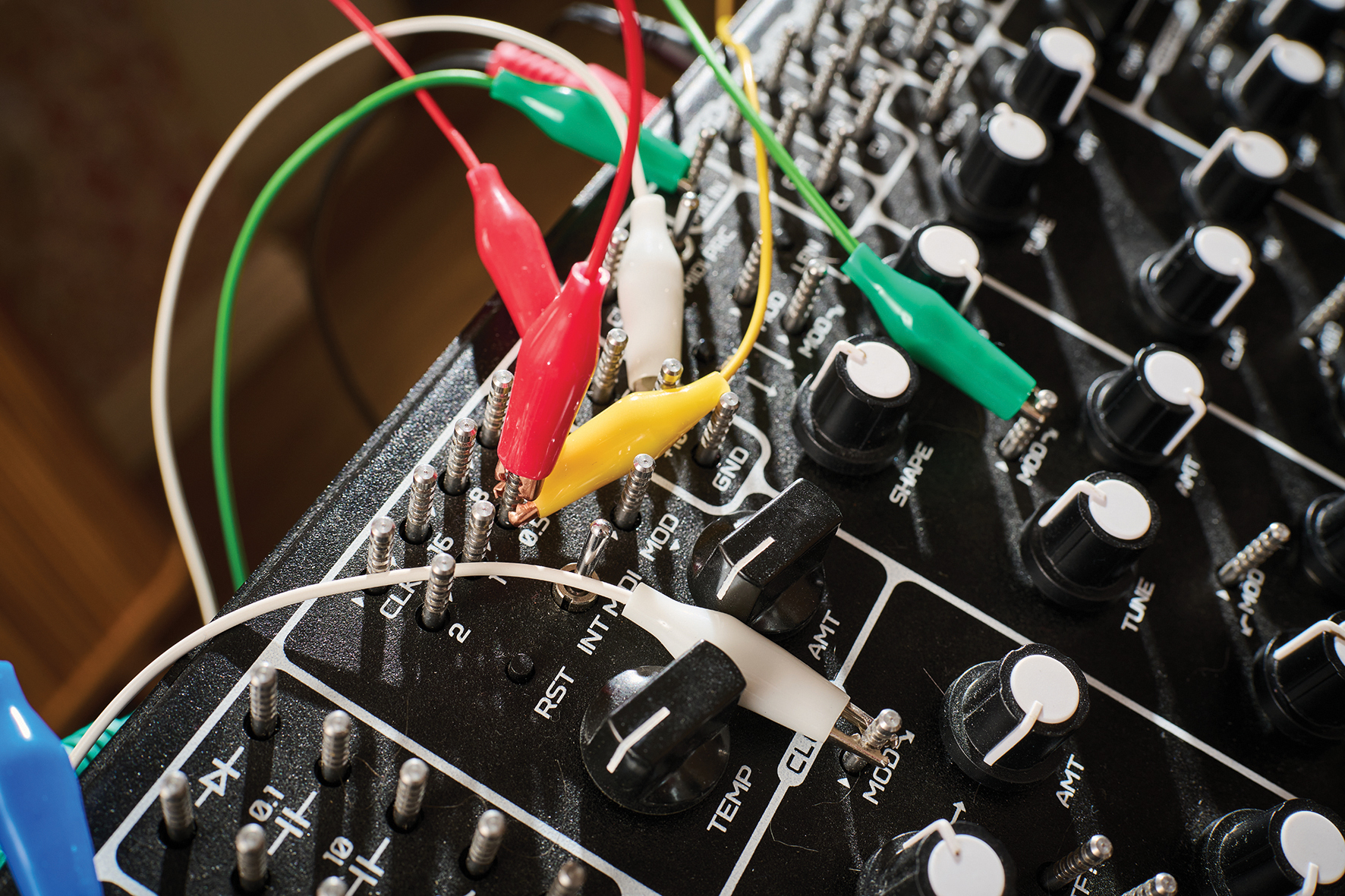

“At the heart of my setup is the SOMA Electronics Pulsar-23. I’m using that to create very low kick drums and the way I’ve set it up lets me use one of the potentiometers to tune them higher and lower so the notes aren’t constant throughout the whole set. I also use the Pulsar to create acidy synth voices, snare claps and hi-hats. It has these completely unquantised CV loop recorders for all the sounds, which works great for wonky experimental stuff but it’s a bit too much for straight-up techno, so I’m using it quite conservatively.”

How are you sequencing it?

“I have a Torso Electronics T-1 sequencer sat in front of it and I’m using the MIDI out to sequence the Pulsar because I feel that techno works best when the sequences are quite strict. A lot of sequencers have random functions that you can add, but the Torso’s sequencer randomisation is more musical and human-sounding so it’s great for giving nice variations to hi-hat patterns etc. If I’m muting different drum channels, I can do that with one hand by double-tapping certain keys and selecting and unmuting whole selections while I’m tweaking other parameters.

“The thing with live gear is that until you’ve actually tried something live, you’ve got no idea whether it’s going to sound good or not. It’s strange how some pieces of gear sound great in the studio but the body of the sound feels totally lost in a live environment. To me the Pulsar sounds monstrous live – it’s kind of shocking how heavy it sounds, which makes it fun to play with.”

You have some other modules attached to the Pulsar?

“I’ve got a granular sampler called the Nanobox Lemondrop, which lets me create these short, stabbing riffs and longer-sounding pads. I’m feeding its output through the Pulsar and have patched it in a way that lets me have a potentiometer for the dry signal and another sending a signal to the Pulsar’s delay. That’s also being MIDI triggered by the Torso’s sequencer, which also gives the sounds a bit more musicality.”

What’s the other sampler you’re using?

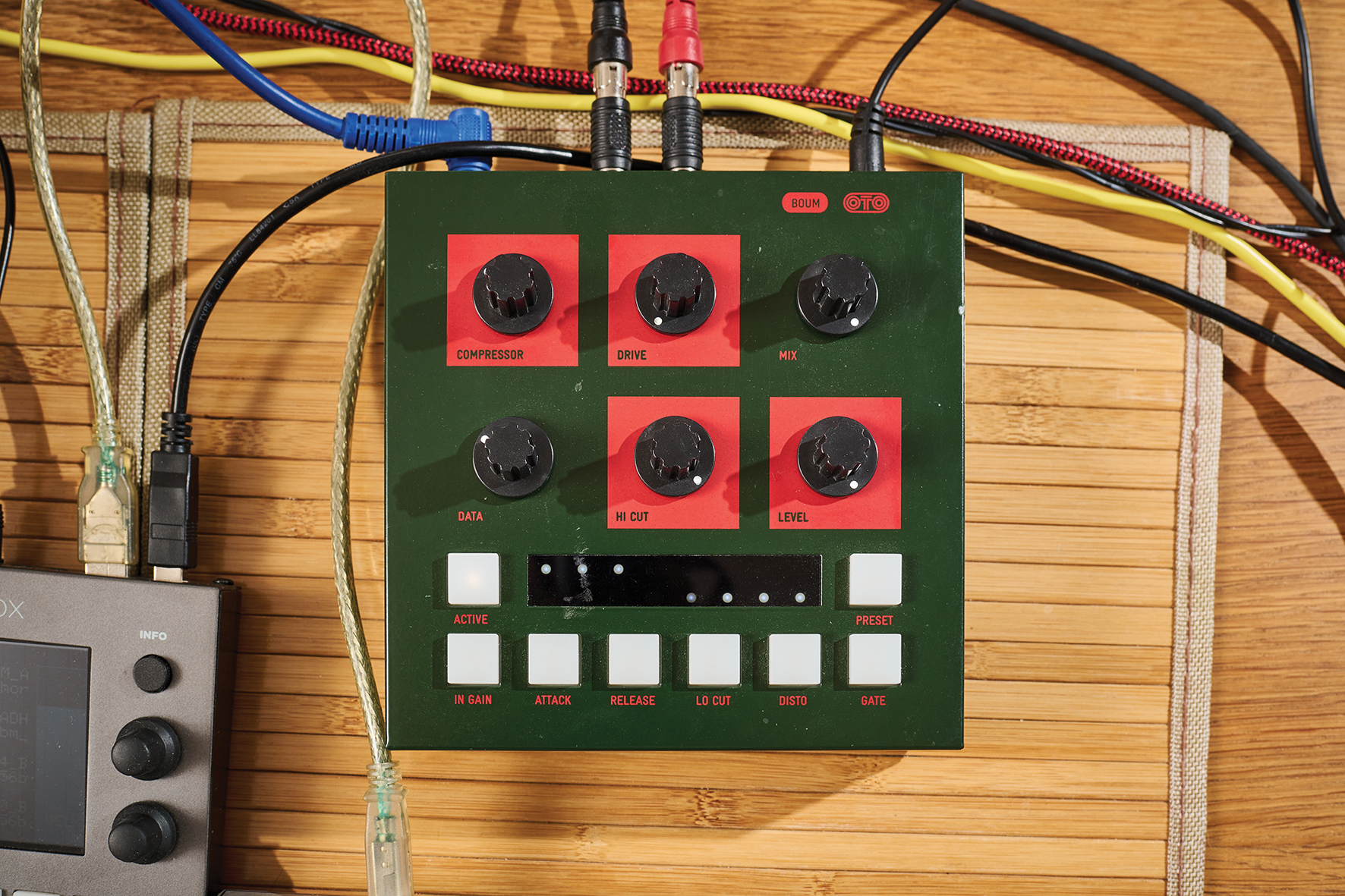

“That’s a 1010music Blackbox. That’s also being retriggered from the Torso, with the cable coming via the Lemondrop. That gives me some more pads and conventional 909-style percussion samples and atmospheres. I’ve also connected an old Faderfox FX3 MIDI controller to the Blackbox so I can control the filters and volume controls in a way that’s more hands-on. The output from the Blackbox is then going into an OTO Machines BOUM compressor/limiter to squash everything and the whole setup is also being routed through a tiny little Moukey MAMX1 audio mixer.”

Was there a lot of planning involved in combining these technologies or did you just stumble upon the setup?

“It was trial and error really – I just tried out different pieces of gear to see what I liked the sound of, until I found a combination that works. It was also really important that everything could fit into a small wheelie case that I could carry as hand luggage onto a plane. That gave me the perfect excuse to limit myself and added a sense of self-discipline.”

How much deviation does this setup allow from the initial starting point of a track?

“The first sequence, which is titled Oak Bank on the album, can land in many, many different directions. Using the sequencer in this way means I’m more pre-prepared but still have a lot of flexibility to work with.

“With modular improvisation, it can be very frustrating for the audience waiting for a performer to find what they’re looking for, so this setup is an attempt to tighten things up with a coherent starting point yet add a high degree of flexibility for when I want to go off on a tangent and feel things out or make things sound deeper or heavier.”

How did the live process translate to recording the Crash Recoil album in a studio environment?

“I’d worked with those tracks live for 10 months and knew what those songs were and the possibilities they could bring, so I literally used the same gear to create the source material. All of the sound sources and sequences were taken from the live set, but it’s not a live album or a recording of a live performance.

“I’d record a synth part, modulate and manipulate it and that would be the take. Then I’d repeat that process for all of the possible parts for the song, look at what I had and arrange everything in Ableton. Other than some phasing or stereo delay, I didn’t add any external software sounds or parts and the remainder of the process was just basic arranging and mixing.”

As you alluded to earlier, did the takes sound different in the studio next to how they initially sounded live?

“I guess the tracks sounded a lot more stripped back and raucous in the live set as when I’m performing I’m often reacting to how powerful the sound system is. When I work in the studio it’s a very introverted process, but performing live is different because you have that audience interaction.

“This album came out in a very honest way because when I’m performing live there’s no permanence, but in the studio you can be very cautious and there can also be a lot of self-censorship in terms of deciding what’s cool and what’s not. This time I decided to just let everything out without those restrictions and I think that’s why it’s more melodic with a lot of subliminal influences in it. After having worked on the tracks in the studio, they probably come across a bit more layered and dense.”

You’ve mentioned hearing influences on the album such as King Tubby or The Cure. Is that entirely subliminal?

“I didn’t sit there and think I want to make this album sound like King Tubby: I mentioned those people because I heard those influences when I listened back to the finished work. It was more about the way he used a parametric on a mix: I was changing the EQ and filter on the hi-hats and using a lot of delays too. It might not be your usual techno influence, but I mentioned The Cure as I feel that a lot of the melodic elements have similar harmonic thing going on in them.”

How is your studio shaping up as a whole?

“I may have mentioned it before but there really isn’t much of a studio to speak of. Currently, I’ve got a folding table for my live setup, some monitor speakers, an audio interface and a whole lot of mess surrounding that.

“I don’t have a whole load of gear permanently set up, although I suppose I am a gear hoarder because even when I think I’ve finished with a piece of gear I often find a different way of combining it with something else. At the moment, everything else is locked away somewhere in a cupboard [laughs].”

Have you ever been an in-the-box producer?

“I did make a bunch of music in the computer for quite a while but it’s always been a struggle for me. I’ve come to realise that I’m not really a programmer; I’m more of a hands-on improviser. That’s why I’ve gone back to using hardware a lot more and just use the computer as a multi-track recorder for arranging and mixing.

“Ultimately, it’s about knowing yourself and realising what works for you rather than looking at person X and deciding to make music in the same way they do. But if you see a piece of gear and think it looks amazing then just follow your nose – it can be quite an exciting way to work.”

Is your creative process now completely circular in terms of live work informing studio work and vice versa?

“For me, it’s important to find new approaches and new ways of working because new processes throw up new restrictions and possibilities. This is the first time that I’ve created an album in this way, but I didn’t set out with the intention of touring and then turning those tracks into an album.

“I haven’t thought far enough ahead to decide whether I’d do that again either. Being the impatient and impulsive character that I am, there’s no point. I’ve always found the way that David Bowie worked really inspiring in that he had all these different musical phases and was always interested in different ways of working and then he followed those interests.”

Has this new method resulted in a different sound?

“I wouldn’t have released a techno album this year had I not created Crash Recoil in this way. The process we’ve been talking about has obviously been completely different and that’s definitely had an effect on my sound world. Crash Recoil has a very different feel to anything I’ve previously done, but each album has its own place in time and I see them all as very separate projects.”