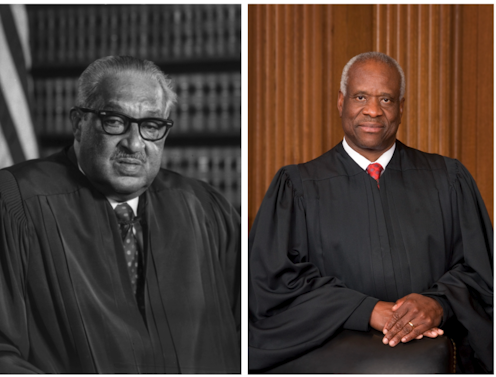

As public attention focuses on Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ close personal and financial relationship with a politically active conservative billionaire, the scrutiny is overlooking a key role Thomas has played for nearly three decades on the nation’s highest court.

Thomas’ predecessor on the court, Thurgood Marshall, was a civil rights lawyer before becoming a justice. In 1991, in his final opinion before retiring after a quarter century on the court, Marshall warned that his fellow justices’ growing appetite to revisit – and reverse – prior decisions would ultimately “squander the authority and legitimacy of this Court as a protector of the powerless.”

His prediction has been quoted by Supreme Court decisions since, including a three-justice dissent from the June 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling that declared there was no constitutional right to reproductive choice and overturned Roe v. Wade.

In his concurrence with the majority decision in that case, Thomas declared his opposition to Marshall’s principle, lamenting that the court had not done more to pare back its prior work. “In future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents,” Thomas wrote – directly implicating Americans’ rights to sexual privacy and same-sex marriage.

Throughout Thomas’ tenure he has pushed the Supreme Court to revisit prior decisions that embraced robust rights for society’s most vulnerable, and to replace Marshall’s vision with one more amenable to the powerful than the powerless. And in writing my book tracing the lives and work of both justices, I have seen the fruits of this effort multiply over the past decade.

A shield for those in need

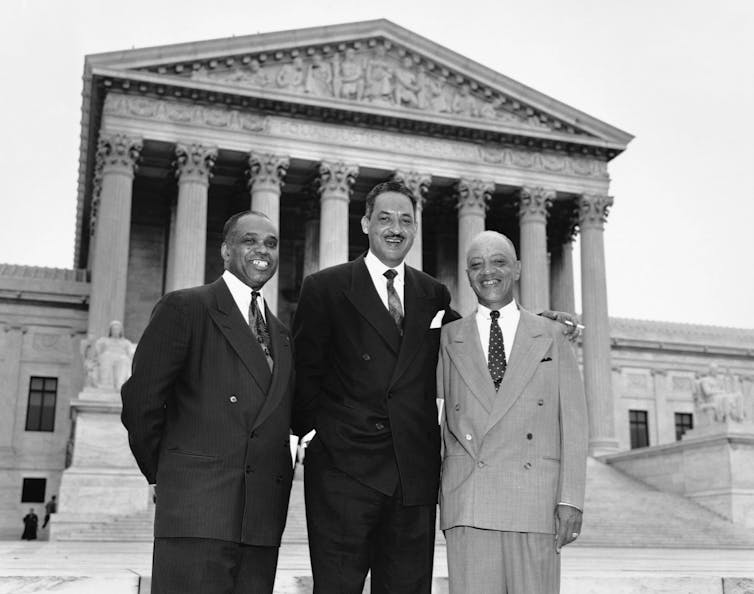

Few phrases could so aptly capture Thurgood Marshall’s vision of the court’s work as “protector of the powerless.” And few, if any, Americans have done as much to make that vision a reality.

Marshall’s work to advance Black citizenship is well known, but he also fought for expanded rights for women and the indigent, the accused and convicted, adherents to marginalized religions and those with unpopular viewpoints.

At the root of Marshall’s jurisprudence was a hope that while law could be a powerful tool of oppression, it might also be a shield.

As he wrote in that final dissent, in Payne v. Tennessee, enforcement of constitutional rights “frequently requires this Court to rein in the forces of democratic politics,” to protect the powerless from the tyranny of the majority.

While his Payne dissent criticized the court for reversing itself, Marshall was no stranger to calling for reconsideration of established law. Marshall’s signature accomplishment as a lawyer in Brown v. Board of Education was to convince the court to overturn the doctrine of separate but equal that had emerged after the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

As a justice, Marshall argued passionately and repeatedly that the death penalty violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment, leading to a brief period where it was considered unconstitutional.

The distinction between Marshall and Thomas is not really about whether the court should reverse past decisions but simply which ones.

While Marshall willed the court to become a “protector of the powerless,” Thomas has, I believe, argued not only to scale that vision back, but to advance the interests of the powerful.

Power as a key factor

While last summer’s abortion decision is an obvious example, Thomas has led the court’s assault on precedent in other areas as well.

For example, years before the court invalidated portions of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder, Thomas had argued that the lack of modern voting discrimination made the act unnecessary.

Similarly, recent decisions have followed Thomas’ lead in weakening the vitality of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which fortifies the separation between church and state.

Thomas has even called for the court to reconsider its ruling in Gideon v. Wainwright, which established a constitutional right to a lawyer for indigent criminal defendants.

In each case, it is the powerless who stand to be most significantly affected.

Those in need of constitutional protection in Thomas’ view are more likely to be property owners, corporations making campaign contributions or gun owners.

On affirmative action

Perhaps no topic better captures the distinction between the two men’s views than affirmative action, which the court is considering in a pair of cases from Harvard and the University of North Carolina to be decided this term.

The distrust of government that fuels many of Thomas’ perspectives is never more personal than in cases about the use of race in college admissions. He has railed against affirmative action, saying it brands Black people in prominent positions with a “stigma” about “whether their skin color played a part in their advancement.”

Indeed, Thomas claims his position requiring colorblindness is a better path toward full Black citizenship. He has made that claim even in situations where he knew it would result in more limited access to opportunities for Black students in the short term.

Marshall always looked at the issue from a different perspective, arguing that access to opportunities was essential not only for the Black students affected but for the nation at large.

“If we are ever to become a fully integrated society, one in which the color of a person’s skin will not determine the opportunities available to him or her,” Marshall wrote in 1977, “we must be willing to take steps to open those doors.”

It was access for the powerless that Marshall thought ought drive the thinking of the court.

But this summer, the court may finally embrace a different vision on affirmative action, coming again to a position Thomas has been advocating for decades.

That turn would be yet another reversal squandering Marshall’s vision of the court.

Daniel Kiel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.