Concerned that many people won’t have enough retirement savings even with compulsory superannuation, since 2003 the Australian government has had a scheme to encourage low and middle-income earners to voluntarily put more into superannuation.

The Superannuation Co-Contribution Scheme currently provides 50 cents for every dollar voluntarily contributed, up to A$1,000, by anyone earning less than $42,000. (There are tapered co-contributions for those with incomes up to $57,000.)

To date the scheme has cost more than $10 billion – or $12.7 billion in today’s dollars. Last financial year it paid out about $127 million. Over the next three years it is expected to cost $365 million.

So what is it achieving? Not much, it turns out.

Our analysis of taxation data since 2000 suggests the scheme has made little difference to lifting voluntary super contributions by low and middle-income earners.

Most significantly, our findings indicate the scheme does little more than provide a bonus to those who would have put money into super anyway.

Given the need to rein in public debt, the new Albanese government should consider discontinuing the co-contribution scheme as “low-hanging fruit” – an easy budget cutback that will harm few people.

Read more: How to camouflage $150 billion in spending: call it 'tax expenditure'

How we analysed the scheme

The co-contribution scheme was introduced 2003-04 by the Howard government as part of its “Better Superannuation System” reforms meant to encourage higher contributions.

Initially the co-contribution was dollar-for-dollar. In 2004-05 it was increased to $1.50 for every dollar. In 2009-10 the Rudd government reduced it to $1 and in 2012-13 the Gillard government cut it to 50 cents.

To evaluate the scheme, we used a data set from the Australian Taxation Office known as the Australian Longitudinal Information Files (ALife). This contains a 10% anonymised sample of Australian superannuation and tax records that currently goes back to 1991.

We analysed records from 2000 onwards, looking at the super contributions of anyone who earned less than $80,000 for at least one year between 1999-2000 and 2016-17. This totalled 1.3 million individuals. Of these, 730,000 were eligible for a co-contribution in at least one year.

Before the scheme began, about 14.5% of those subsequently eligible for the co-contribution made voluntary contributions to superannuation.

Our analysis shows only marginal effects on the rate of voluntary contributions – even when the co-contribution rate was double or three times higher than it is now.

At a co-contribution rate of 50 cents on the dollar, the scheme has increased contributions by 1 percentage point.

At the previous rate of $1, the increase in super contributions was 1.5 percentage points. Even at the past rate of $1.50, it was just 3.5 percentage points.

In reading these estimates it’s important to note they aren’t simply percentage changes to the 14.5% contribution rate prior to the scheme. They are generated by an econometric model that has allowed us to measure changes in super contributions when people gain or lose eligibility for the co-contribution scheme, then compare those to changes in contributions of people whose eligibility did not change.

Who has benefited most?

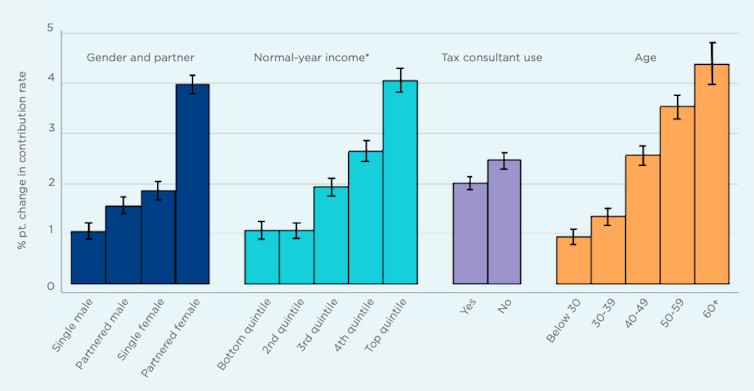

The biggest increases in contributions were by high-income earners who happened to qualify in a particular year due to a temporary drop in income, as well by partnered women.

Those normally in the top 25% of income earners were four times more likely to take advantage of the scheme than those normally in the bottom 25%.

Women with partners were more than twice as likely to contribute as single women or men with partners, and four times more likely than single men. The likely explanation for this is that the scheme has been used by women with higher-earning partners.

The following chart shows these average effects across the life of the scheme.

Impacts on sub-group voluntary after-tax contribution rates

Strikingly, our analysis indicates those taking advantage of the scheme would have made slightly higher voluntary super contributions without any co-contribution.

The difference is slight – on average of $20 to $50 a year, depending on the co-contribution rate – but the whole point of the scheme is to encourage higher contributions, not provide a subsidy for people to contribute at the same (or a marginally lower) rate.

Read more: Yes, women retire with less than men, but boosting compulsory super won't help

Failing to make a difference here and overseas

These disappointing results from the scheme are in line with findings of similar schemes in the United States and Germany.

There are two possible reasons.

The first is that people may be unaware of the scheme. But we find no evidence for this. For example, our analysis indicates those who use tax agents – who are likely to be aware of the scheme and pass on such knowledge to their clients – are no more likely to use the scheme than those who do their own tax return.

The second reason is the more obvious one.

Most people on lower incomes don’t have spare cash to put into super. This is why increases have been minor even with a matching payments rate three times higher than now. If you don’t have the spare cash, it doesn’t make much difference a what rate the co-contribution is set.

Our findings cast serious doubt on the point of the superannuation co-contribution scheme. Despite its relative simplicity and generosity, it has done little to lift the retirement savings of low and middle-income Australians as intended.

The real beneficiaries of the scheme have been the small minority of eligible people who were already contributing. For them, this has been a windfall that has allowed them to reduce their personal contributions while still achieving their desired contribution levels.

Read more: Retirement incomes review finds problems more super won't solve

Cain Polidano receives funding from Australian Research Council.

Ha Vu receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Marc Chan receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Roger Wilkins receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.