For Rishi Sunak, winning the support of Tory MPs was the easy part – now he faces a real battle to gain the backing of Conservative members uneasy about his record in office and his part in the downfall of Boris Johnson.

Once the golden boy of the Tory Party, Mr Sunak enjoyed a meteoric rise under Mr Johnson and for so long appeared to be his most likely successor.

At the start of the pandemic, he was the most popular politician in the country as he rolled out an unprecedented furlough scheme which saved millions of jobs as the economy ground to a halt.

But now the former chancellor faces a fierce fight to gain the keys to No 10, denounced by allies of the Prime Minister as a treacherous “snake” who brought down his former mentor.

His ambitions had been scarcely concealed since the day he entered No 11, with personalised branding on carefully-curated social media content to boost his public profile along with a concerted campaign to woo MPs which made him the frontrunner in the Westminster stage of the leadership contest.

Born in 1980 in Southampton, the son of parents of Punjabi descent, Mr Sunak’s father was a family doctor and his mother ran a pharmacy, where he helped her with the books.

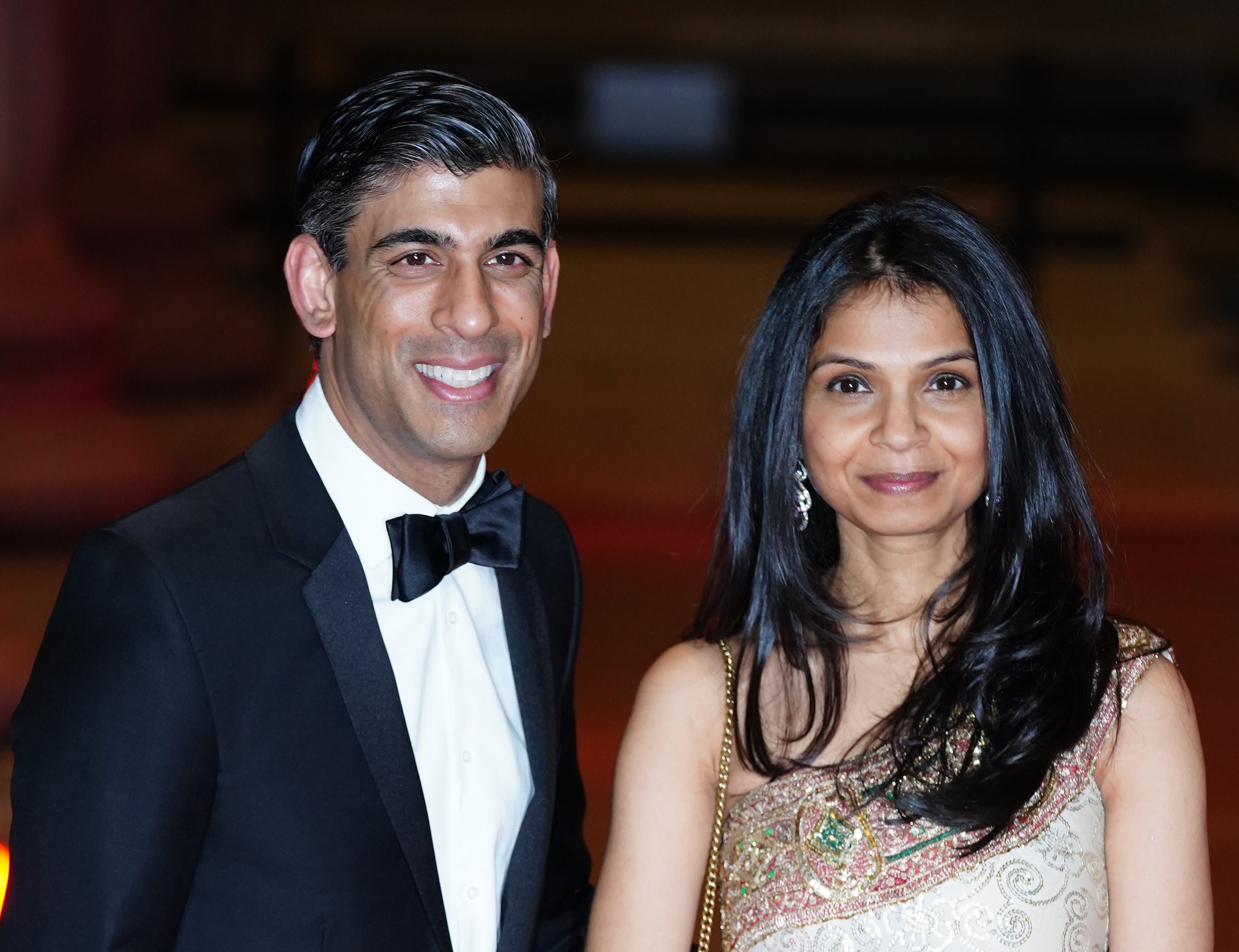

After private schooling at Winchester College, where he was head boy, and a degree in politics, philosophy and economics at Oxford, he took an MBA at Stanford University in California where he met his wife, Akshata Murty, the daughter of India’s sixth richest man.

A successful business career, with spells at Goldman Sachs and as a hedge fund manager, meant by the time he decided to enter politics in his early 30s he was already independently wealthy.

In 2014, he was selected as the Tory candidate for the ultra safe seat of Richmond in North Yorkshire – then held by William (now Lord) Hague – and was duly elected in the general election the following year.

In the 2016 Brexit referendum he supported Leave, to the reported dismay of David Cameron who saw him as one of the Conservatives’ brightest prospects among the new intake.

Given his first Government post – as a junior local government minister – by Mr Cameron’s successor, Theresa May, he was an early backer of Mr Johnson for leader when she was forced out amid the fallout over Brexit.

When Mr Johnson entered No 10 in July 2019, there was swift reward with a dramatic promotion to the Cabinet as treasury chief secretary.

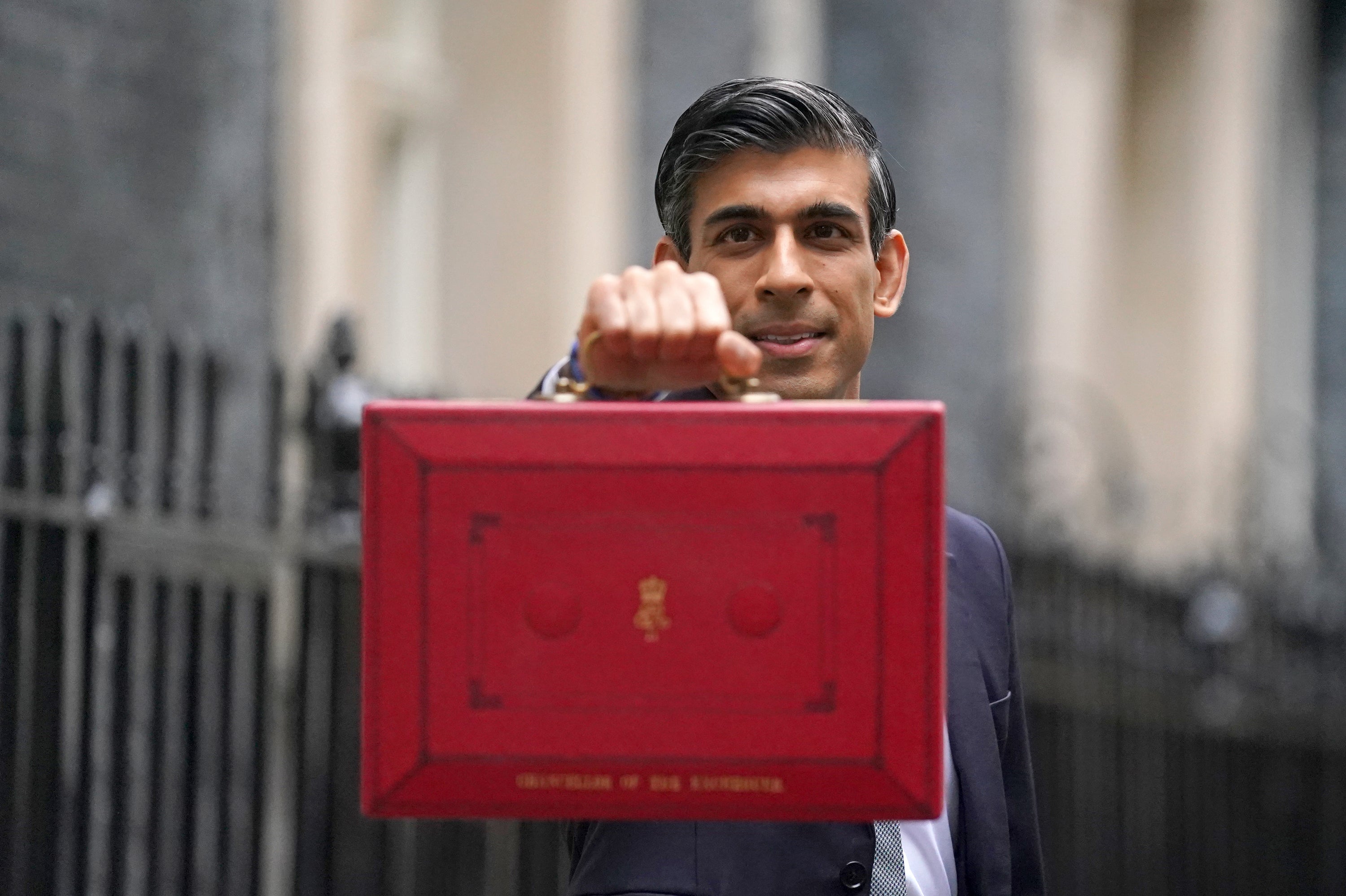

An even bigger step up followed in February 2020 when chancellor Sajid Javid quit after rejecting a demand to sack all his advisers and Mr Sunak was put in charge of the nation’s finances, at the age of just 39.

The increasingly rapid spread of Covid-19 meant his mettle was swiftly tested. Within a fortnight of his first Budget he was effectively forced to rip up his financial plans as the country went into lockdown.

The new chancellor, who saw himself as a traditional small state, low tax Conservative, began pumping out hundreds of billions in government cash as the economy was put on life support.

But as the country emerged from the pandemic, some of the gloss began to wear off amid growing tensions with his neighbour in No 10 and anger among Tory MPs over rising taxes as he sought to rebuild the public finances.

To add to his woes, he was caught up in the “partygate” scandal, receiving a fine, along with Mr Johnson, for attending a gathering to mark the Prime Minister’s 56th birthday, even though he claimed only to have gone into No 10 to attend a meeting.

There were more questions when it emerged his wife had “non dom” status for tax purposes – an arrangement which reportedly saved her millions – while he had retained a US “green card”, entitling him to permanent residence in the States.

For a man known for his fondness for expensive gadgets and fashionable accessories – and who still has an apartment in Santa Monica – it all looked dangerously out of touch at a time when spiralling prices were putting a financial squeeze on millions across the country.

His frustrations with Mr Johnson’s chaotic style of government – as well as a deepening rift over policy – finally spilled over when he dramatically resigned, prompting the rush for the door by other ministers that forced the Prime Minister to admit his time was up.

It now remains to be seen whether the one-time heir apparent can claim his title, or if he will discover – as others in Westminster have before – that “he who wields the knife never wears the crown”.