Many North Americans plan to travel this summer to catch up on lost experiences, following two years of COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions. This so-called revenge travel has the potential to raise the number of drownings, as more people choose to enter the water, even when the conditions aren’t ideal.

Recent history shows that every time government lockdowns were lifted across North America, people flocked to the nearest beach, often their only opportunity for an impromptu vacation. Despite travel restrictions, the Great Lakes region had a greater-than-expected number of fatal drownings in 2020.

A combination of reduced funding to lifeguarding programs, cancelled swimming lessons, large beach crowds, warm weather, high-water levels and self-isolation fatigue all contributed to the increased number of fatalities.

A new Smart Beach pilot program on Lake Huron, in Kincardine, Ont., will help beachgoers stay safe. Smart Beach uses innovative technologies to collect and analyze water and weather conditions to provide beachgoers with real-time information on local water conditions, including rough surf and rip currents.

The cost of drownings

Rough surf and nearshore currents are associated with approximately 50 drowning fatalities per year in the Great Lakes. Boys and men under the age of 24 make up a disproportionate number of those fatalities, and most occur on unsupervised beaches or during periods where lifeguards and other active warning systems are absent.

While the loss to family and friends is immeasurable, there are also direct and indirect economic costs, which range from $4,500 per hour to operate a local search and rescue vessel to $16,000 per hour for a Coast Guard helicopter for search and rescue operations over a larger area. Survivors may accrue additional costs from a visit to an emergency room or from lifelong care in specialized facilities.

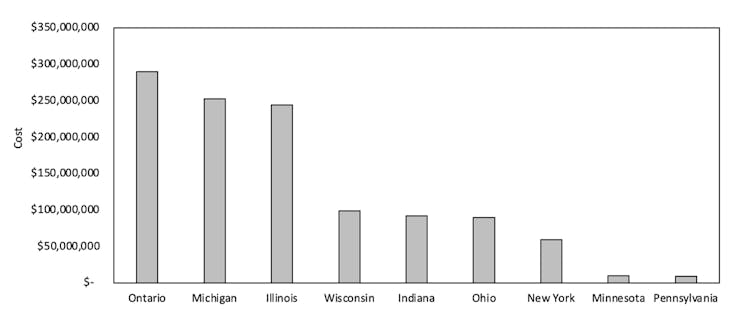

Fatal drownings have far greater economic costs. Economists use a calculation called the value of a statistical life to estimate the monetary value of reducing the risk to one statistical death. My colleagues and I used this value along with the average life expectancy of a drowning victim, to estimate the annual average economic burden of all drowning fatalities in the Great Lakes region is about US$105 million.

Between 2011 and 2020, the total economic cost of drownings in this region alone was over US$1.1 billion. The costs of drowning fatalities, whether on a personal, social or economic basis, are severe — and could increase with revenge travel.

It is important to note that the economic impact for drowning fatalities in the Great Lakes region does not consider the significant emotional impact and personal loss associated with drowning events.

Revenge of the tourist brain

With the return to travel, drowning risk increases with a simple cognitive error referred to as tourist brain. Tourists tend to think beach access points and resorts are located next to safe swimming areas, particularly when visual cues such as manicured paths, promotional posters and other beach users’ behaviour appear inviting.

Read more: Why your tourist brain may try to drown you

Beachgoers may also be unaware of safety strategies, such as what they should do if they’re caught in a rip current. Many people simply don’t pay attention to warnings and those tired of COVID-19 restrictions may further ignore warnings or safety controls, especially if they think lifeguards are being overly cautious. Peer pressure and the behaviour of others also play important roles.

Record inflation and high gas prices mean that local and non-holiday beaches, many of which are not patrolled by lifeguards, may see larger crowds, which could put swimmers and bystanders who attempt rescues at greater risk.

Revenge travel will only exacerbate our tourist brain tendencies to make unsafe decisions at the beach. Considering the direct costs and economic burden of drowning fatalities now is the time for governments to investment in education programs, lifeguard programs and warning systems that people trust and will follow.

Chris Houser receives funding from MITACS in support the Smart Beach project.

Alex Smith's post-doctoral position is funded through the MITACS Accelerate Fellowship in support of the Smart Beach project.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.