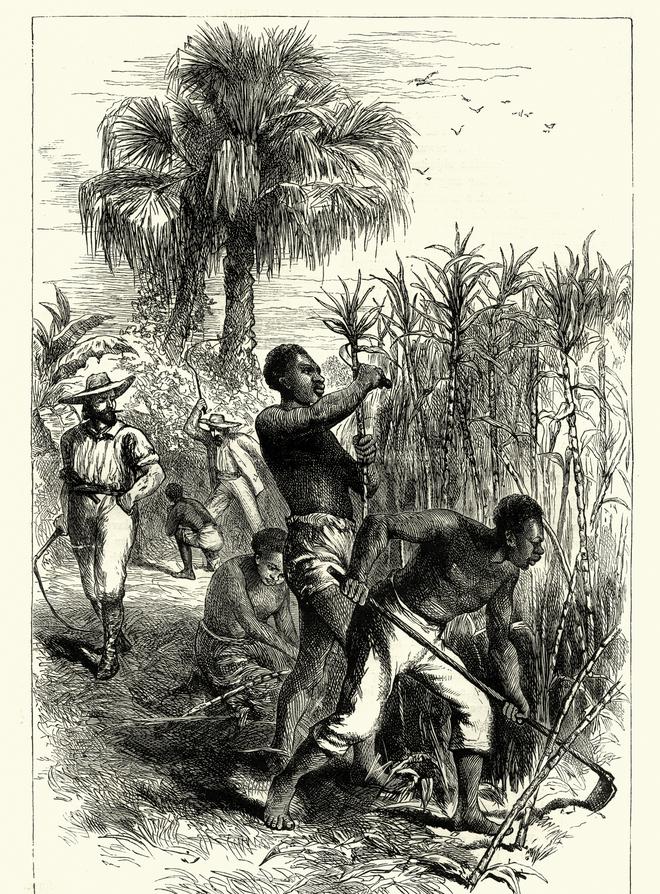

Since the 17th century sugar has dominated the world of western commerce. Once only affordable for the rich, it is now one of the most ubiquitous products, present in most things we consume. For long, sugar production was dependent on the punishing labour of millions transported from Africa and enslaved to toil in brutal conditions in sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean and the Americas. Published shortly before Dutch King Willem-Alexander apologised for his kingdom’s role in the slave trade, Ulbe Bosma’s book, The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, And Environment Over 2000 Years, is a global history of sugar from its early origins in India and highlights Asia’s crucial role in shaping the world of sugar. Excerpts from an interview.

What drove you to add to the considerable literature on sugar?

Commodity histories of cotton and sugar have become increasingly popular indeed. My book is different since it is a comprehensive history of sugar and it spells out the crucial role of India, China, Indonesia and of the European and North American beet sugar industries in shaping the world of sugar.

How did sugar become so indispensable?

To put it in one sentence: white sugar was a key commodity in emerging global capitalism and it became affordable and therefore ubiquitous with globalisation.

Abundantly available in Asia what necessitated the cultivation of sugarcane in the Caribbean and the Americas?

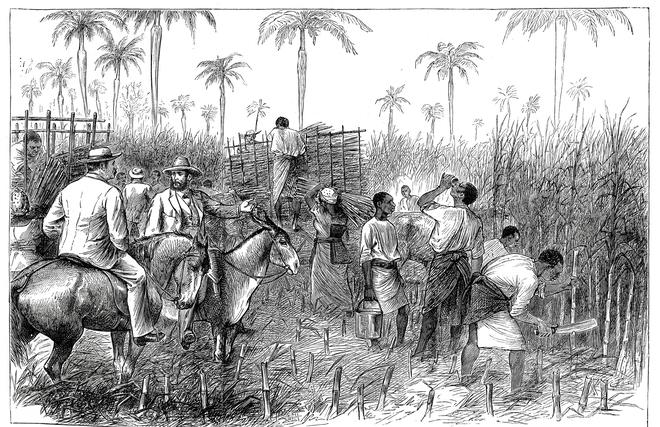

At the time the Spaniards and Portuguese introduced sugar plantations in the Americas in the 16th century, the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean was much easier than to India, let alone Indonesia. The Atlantic sugar complex had its own trajectory and momentum. It was only in the 19th century that considerable quantities of sugar from Java, and India, reached the European markets, not least because of the anti-slavery movement.

Did excessive investment in slaves and infrastructure in the Caribbean and the Americas prevent the sourcing of sugar from India and the rest of Asia?

As brought out in my book, British slave holders were well-entrenched in British Parliament enabling them to blockade the import of sugar from India through high duties on sugar from outside the West Indies. The cheapest sugar in the world could be found on the waterfront of Calcutta, but until 1835 duties prevented this sugar from entering Britain.

How strong is the case for reparations from former slave-trading countries?

Regarding the reparations debate, I think as historians we are tasked to provide our societies with relevant facts but I do not think it is wise to position ourselves in such a debate. Also let us not forget that Asians, predominantly Indians, Chinese and Japanese, were also transported to work in near-slave conditions and like Africans significant numbers died in transit.

How could Europe, in the age of Enlightenment, take to the slave trade?

Some historians downplay the cruelties of slavery by saying they were perpetrated long ago when people had no notions about human rights. That is nonsense. The slave trade was considered reprehensible by many in the 16th century itself. But in its time the prospect of economic gain put aside existing opinion that enslaving people was un-Christian and sinful. What is not to be missed are the devastating social and economic consequences of the slave trade for Africa persisting to this day.

How important was sugar to the rise of a global capitalist economy?

Sugar was pivotal in the rise of our global capitalist economy. The point I also want to make is that global capitalism has been crucial in shaping our current consumption patterns including our overconsumption of sugar. Moreover, only through a constant violation of human rights could sugar become a cheap mass commodity. The relentless exploitation of labour did not end with the abolition of slavery but continues to this day.

Who in the West stood up for exploited migrant and indentured labour?

Interestingly, only the Communist and Syndicalist labour organisations took a principled stance against discrimination of immigrant workers, and fought for them through organising strikes. Such labour activism disappeared after World War II.

Did the transatlantic slave trade enrich Europe and America and finance the industrial revolution?

To my mind, undoubtedly. The Atlantic slave-based commerce contributed significantly to the rise of the West in terms of banking, industry, shipping and so on. My colleague Prof. Brandon and I calculated that by 1770 about 10% of The Netherland’s economy derived from slave-based commerce, sugar making up half of it.

How much of sugar today comes from beet?

Today beet sugar makes up only 20% of the global sugar production, the rest comes from sugarcane. This is good news for cane sugar-producing countries.

Why is sugar losing out to High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)?

The entire sugar producing world, the Caribbean nations, the Philippines, and India, saw a slump in the price of sugar because the U.S. beverage industry shifted to much cheaper HFCS in the 1980s.

Can humanity get over its unhealthy sugar addiction?

In some western countries their high sugar consumption is declining but too slowly to prevent an explosion of diabetes-2 cases. Like beet or cane sugar, HFCS is a serious health hazard too. Unless governments curb their use, we face a public health catastrophe.

The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2000 Years; Ulbe Bosma, Harvard University Press/Harper, ₹699.

The writer teaches at IISc, Bengaluru.