Suburbia and the American Dream are perpetually connected, the former’s seemingly uniform pristineness acting as a primary signifier of all that the latter promises. For close to a century now, the two have been celebrated, criticised, performed and marketed across literature, art, film, and advertising, while the material pillars of picket-fenced neighbourhoods have been emulated by architects and city planners around the world.

‘I remember as a child being glued to the television, asking my mother why Americans lived in such big houses, surrounded by lawns, with a couple of cars in the garage,’ recalls Spanish journalist Philipp Engel, the curator behind ‘Suburbia. Building the American Dream’, on show at Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (until 8 September 2024). ‘There was always [in these shows], the exterior shot of a house, very similar to the photos in real estate agency windows.’

‘Suburbia. Building the American Dream’ at CCCB

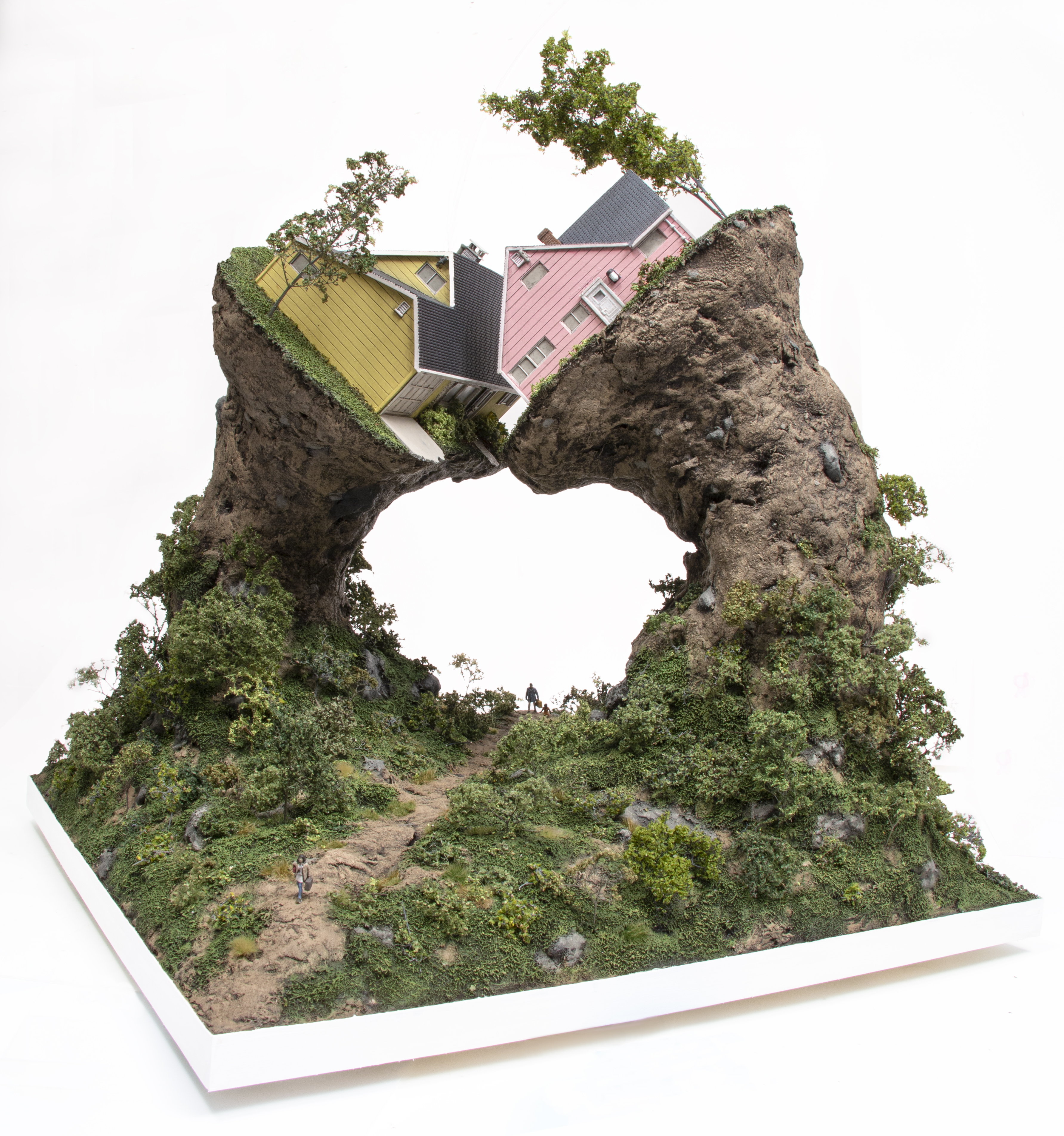

An exhaustive survey into the ‘suburban desire’ generated largely by American pop culture, the exhibition employs photography, painting, audiovisuals, literature and everyday objects to examine how these archetypal residential areas became so prevalent in the States and so widely duplicated elsewhere, concurrently addressing aesthetics while engaging with their social, geographical and political characteristics.

Relaying his entry point, Engel suggests that it’s ‘a subculture with abundant literature. I started at the beginning, which according to Crabgrass Frontier author Kenneth T Jackson, could be Brooklyn of 1814, when the ferry line was inaugurated.’ Indeed, despite misconceptions owing to the swell of attention that post-war suburbia initiated, gated communities began emerging in tandem with the country’s Industrial Revolution. Split into five sections, the exhibition opens with this burst of segregated infrastructure in ‘Planning a Dream’, while rooms such as ‘The Residential Nightmare’ and ‘Post-Suburbia?’ follow.

‘The idea was to answer the question of why Americans live in suburbia, from the most diverse angles,’ continues Engel. ‘Explaining the causes and consequences, showing that this lifestyle of the single-family home did not arise by chance, but was planned to generate an ideology in contrast to others that could be considered anti-American. Quickly we saw that we could structure our discourse through a multidisciplinary exhibition, because although it can be described as imperialist, American culture and imagination are immensely rich and fascinating, largely due to their ambivalence. They offer the best and worst, sometimes at the same time.’

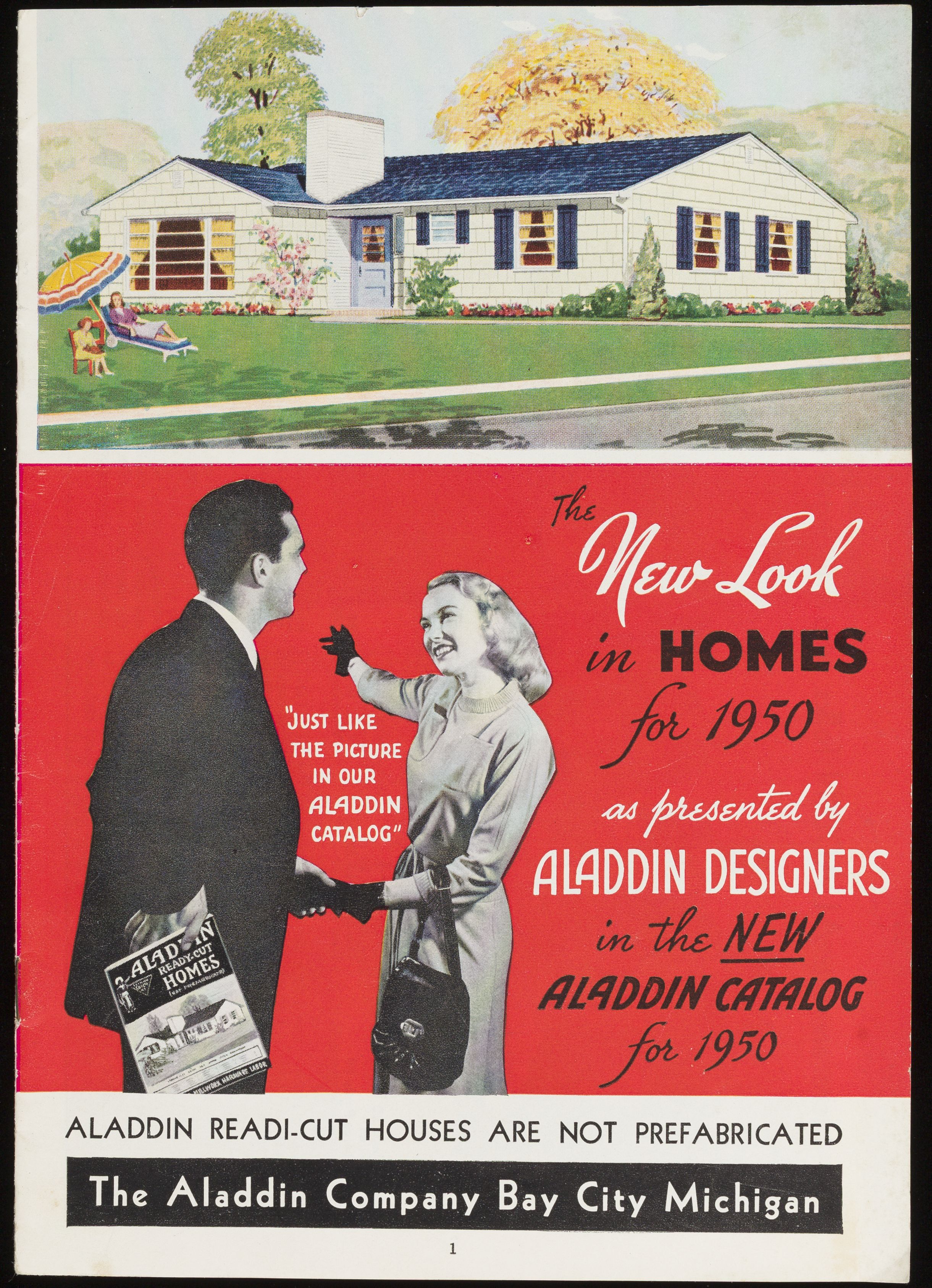

Additionally, he remarks, ‘There is a strong tendency in the collective imagination, to believe that suburbia has been frozen since the 1950s, when the reality is complex. In the exhibition, for example, we contrast Trump’s “suburban dream” speeches with Weronika Gęsicka, an artist working with images intended for advertising in the 1950s, distorting them with Photoshop.’

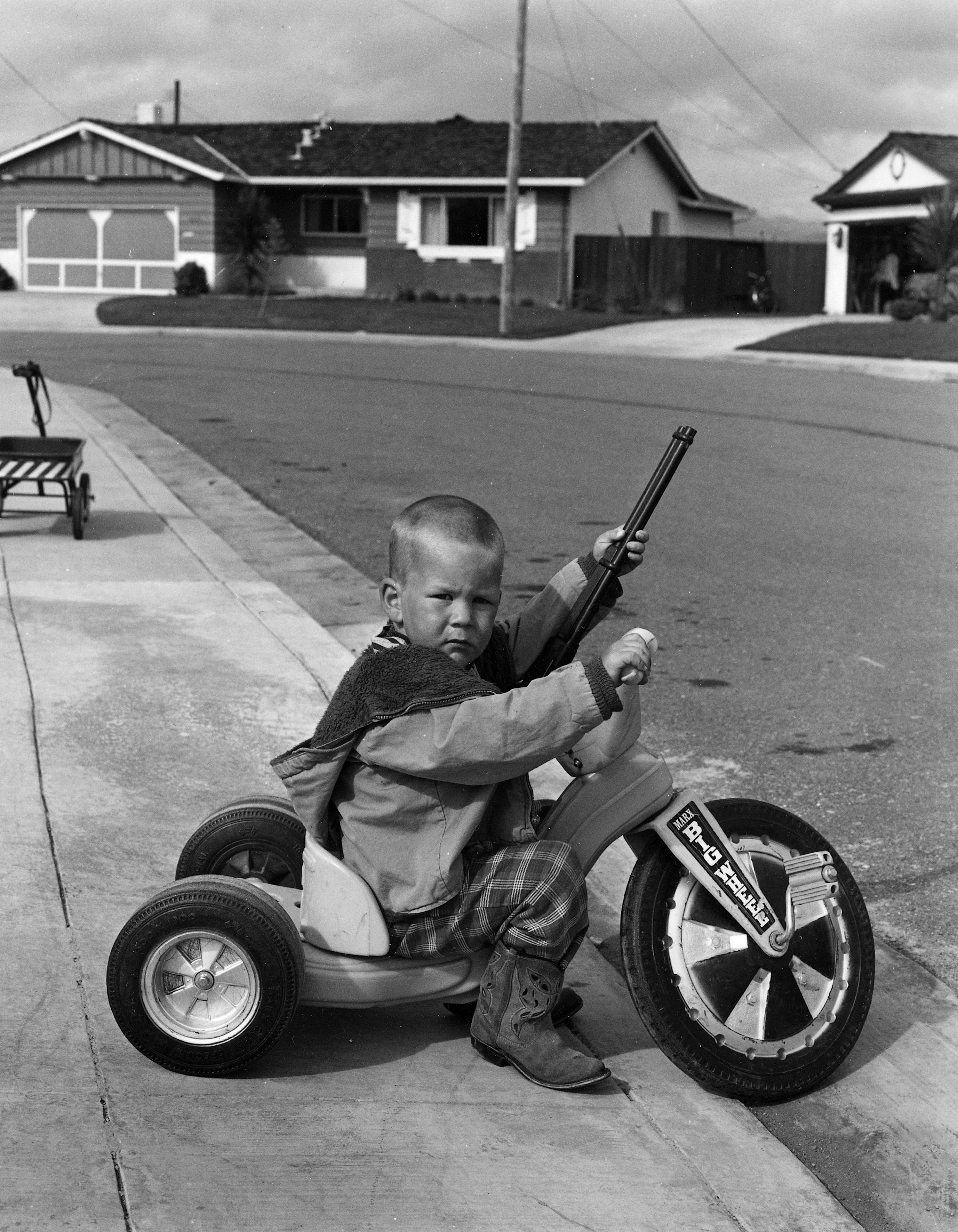

Moreover, beyond Gęsicka’s surreal visuals, an unintentional but ultimately rewarding discovery for Engel was the wealth of photography that honours the subject, and it subsequently became the exhibition’s principal vehicle for storytelling. ‘I come from cinema and literature, and while some things were clear, what I didn’t see coming was that photography by great authors would become the dominant artistic medium,’ he says.

Works by Gregory Crewdson, Joel Meyerowitz and Ed and Deanna Templeton are amongst those that highlight suburbia’s homogeny, while images from Bill Owens’ highly acclaimed 1973 book Suburbia are, significantly, granted a whole room. ‘He was the first to photograph his neighbours, in the early 1970s, and so his work is the heart of the exhibition,’ observes Engel.

Later on, a collaboration with Barcelona-based urban planner Francesc Muñoz ties the exhibition to its immediate surroundings, ushering in a more scientific approach that scrutinises ‘very revealing’ data about water consumption in the region.

Meanwhile, considering the broader impact of Spain’s relationship with suburbia, the curator returns to his observations about what we consume via our screens as he hypothesises about what comes next. ‘For decades, suburbia was a landscape we only saw on television, but there are more and more developments around Spanish cities, and families leaving the centre for the periphery, often convincing themselves they are going to improve their lifestyle with very American arguments,’ he considers. ‘But there is a sustainability problem, and we need to explore how it can be solved, because what we see in the USA always ends up coming here.’

‘Suburbia. Building the American Dream’ is at Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona until 8 September 2024, cccb.org