Need help losing weight or handling depression? How about a pill that lowers cholesterol and treats erectile dysfunction?

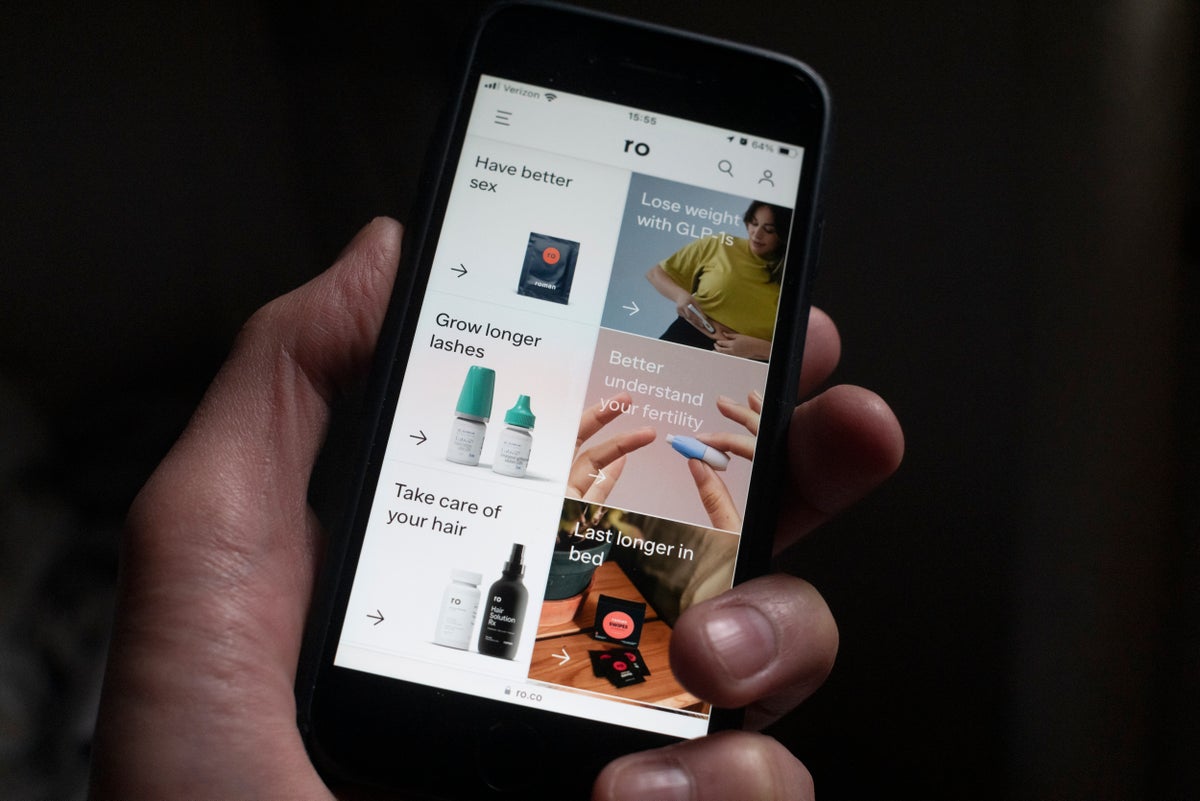

Online subscription services for care have grown far beyond their roots dealing mainly with hair loss, acne or birth control. Companies including Hims & Hers, Ro and Lemonaid Health now provide quick access to specialists and regular prescription deliveries for a growing list of health issues.

Hims recently launched a weight-loss program starting at $79 a month without insurance. Lemonaid began treating seasonal affective disorder last winter for $95 a month. Ro still provides birth control, but it also connects patients trying to have children with regular deliveries of ovulation tests or prenatal vitamins.

This Netflix-like approach promises help for two common difficulties in the U.S.: access to health care and prescription refills. But it also stirs concern about care quality.

“This isn’t medicine. This is selling drugs to consumers,” said Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, who studies pharmaceutical marketing at Georgetown.

The online providers say they screen their patients carefully and send customers elsewhere if they can’t help them. They also think they’ve tapped a care approach that patients crave.

“The growth we’ve seen on our platform is a testament to how people are looking to get the care they need,” Hims spokeswoman Khobi Brooklyn said.

The publicly traded Hims has topped 1.4 million subscribers this year. It expects to pull in at least $1.2 billion in annual sales by 2025.

That pales compared to the $300 billion-plus in annual revenue generated by health care giants like CVS Health. But Hims' 2025 projection is more than eight times what the company brought in at the start of the decade.

Subscription-based health care has been around for years, particularly in primary care, where patients can pay monthly fees to gain better access to doctors. The e-commerce giant Amazon recently entered that niche with a subscription plan that gives some customers access to virtual and in-person care.

Online versions of subscription-based care started growing after the COVID-19 pandemic made Americans more comfortable with telemedicine. That has led to a surge of investor money flowing to companies providing this care, said Dr. Ateev Mehrotra, a Harvard researcher who studies consumer health care.

Many condition-specific plans offer patients regular visits with a health care provider and then recurring prescriptions for a monthly fee.

That simplicity can be attractive, Mehrotra noted.

“You can just get the care you need and move on with life just as you pay for Netflix or whatever,” he said.

Hims debuted weight loss earlier this month after starting a heart health program last summer that includes the combination pill treatments.

Its rival Ro added weight loss last year to a lineup that also includes treatment plans for eczema, excessive sweating and short eyelashes, among other issues.

Lemonaid offers treatment plans for insomnia and high blood pressure. It also touts cholesterol management for $223 a year without insurance. That includes provider visits, lab work and prescriptions for generic medicines.

These companies still push sexual health help, especially on social media. But broader growth remains a priority.

Hims says in a regulatory filing that it sees significant future opportunities in menopause, post-traumatic stress disorder and diabetes.

Ro CEO Zach Reitano noted in an interview earlier this year that his company's obesity treatments are “upstream” to other chronic diseases. He said patients who want help losing weight also care about improving their overall health.

Reitano told The Associated Press he thought one of the health care system’s biggest problems was that “it is not built around what patients want.”

Subscriptions, whether for medicine or meal kits, offer predictable costs and may seem like good deals at first. But customer enthusiasm can fade, and companies may feel pressure to find new business, said Jason Goldberg, chief commerce strategy officer at Publicis Groupe.

The approach also comes with reputational baggage.

RobRoy Chalmers turned to Hims for help with erectile dysfunction. But the Seattle artist decided to cancel his subscription and cut costs after a few months.

He kept receiving bills after he thought he stopped the subscription. He said he emailed and called customer service. He didn’t get a response until he criticized Hims on social media.

“The amount of effort I needed to go through for them to make good was too much,” he said. “This is every subscription-based company in my mind.”

Fugh-Berman worries mainly about care quality. She noted that talk therapy can be as effective as prescriptions for some conditions.

“Mental health care should never just be about drugs,” she said.

She also noted that a diagnosis can change over time. Patients on regular medications must be monitored in case the drug causes problems like higher blood pressure.

Lemonaid Health does that, according to Dr. Matthew Walvick, the company's top medical official. He said Lemonaid routinely follows up with patients to monitor for side effects and update their medical history.

Brooklyn said Hims’ program for mental health care includes psychiatry and talk therapy.

Representatives of both companies say they also encourage patients to get in-person help when needed.

Mehrotra worries more broadly. He noted that overall patient health may get overlooked when customers come to these companies with a specific condition or medicine in mind.

Someone visiting a primary care doctor for birth control may also get screened for depression, he noted.

“These companies are very solution-oriented,” Mehrotra said. “They’re not thinking about that comprehensive care.”

Walvick said Lemonaid collects an extensive patient medical history that delves into issues like smoking or drug use to offer “the best possible comprehensive care.”

Brooklyn said Hims & Hers provides access to safe care for many issues but shouldn’t replace a primary care doctor. She added that every part of the health care system should be focused on improving access.

“The traditional health care system in the U.S. has always been slow to adapt to our changing society’s needs,” she said.